Visitors to Project Lamport, Agrovista’s flagship development trials site in Northants, will be able to see and discuss a wealth of innovative and thought-provoking trials at this summer’s open day. CPM reviews recent findings.

We believe we’ve nailed blackgrass control in physical terms.

By Charlotte Cunningham

There was a time when growers challenged with a potentially overwhelming blackgrass burden felt they couldn’t reliably drill spring wheat on heavy land following a black-oat based cover crop. Project Lamport has clearly illustrated over recent seasons how this can be achieved, while maintaining profitable cereal production, according to Agrovista trials coordinator Niall Atkinson.

The project was originally designed to run for five years, but the decision was taken last year to extend it, despite it clearly having met its initial objective to investigate the effectiveness of a range of cultural controls combined with agrochemical standards to tackle blackgrass.

Agrovista has been comparing 14 different rotational systems on farm-scale plots.

“We believe we’ve nailed blackgrass control in physical terms,” says Niall. “Over five very different seasons the cover crop/spring wheat system has beaten all expectations, keeping a huge infestation of blackgrass at bay and dramatically reducing weed seed return to the soil.

“It’s been a fantastic success, offering a lifeline to many growers who otherwise would have to have given up winter cereal production. However, we believe there’s much more to learn, and that by extending the work we’ll find ways of doing the job even better.”

While Lamport’s main objective remains, soil health now lies at the heart of the project.

“Well-structured soils that drain freely and enable vigorous root growth are at the heart of every successful blackgrass control programme,” says Niall. “And, of course, they also underpin successful crop production.

“We believe this soil research will be extremely valuable to all growers, whether or not they have blackgrass problems, to help develop sustainable farming systems.

“In addition, the political agenda is changing. Subsidy payments may be based around environmental protection, with a particular focus on soil. It’s important to stay ahead and consider all options available for protecting and improving our soils.”

Soil compaction trials are one of the most important introductions at Lamport and are being carried out in conjunction with independent cultivations expert, Philip Wright.

These trials are examining the benefits of various combinations of roots and steel to improve soils whilst reducing the need for heavy, expensive and potentially damaging cultivations.

“After many years of doing it myself I really wonder why we’ve been doing so much cultivation,” says Niall.

“If you think logically, if you’ve just harvested a 10-11t/ha wheat crop there can’t be much wrong with the soil. Yet, once the combine has left the field, it seems we can’t wait to go in and rip everything up.

“The initial study at Lamport in 2017/18 captured visitors’ imagination, so it will be really interesting to see the reaction from this year’s work.”

That initial work on conventionally managed, winter-cropped heavy clay at Lamport clearly showed that using some metal in conjunction with soil-improving cover crops produced better soil structure than roots alone, he points out. This could accelerate the switch to efficient root-only systems based on direct drilling.

In the damp autumn and wet winter of 2017/18, shallow, low-disturbance operations combined with a black oat/berseem clover cover crop resulted in greatly improved wheat establishment and the crop produced an effective canopy much sooner than deep, high-disturbance cultivations.

This season’s trials were established in much drier conditions last autumn. Some plots were again shallow cultivated to a few cm, while others were loosened to either 15cm or 25cm, both with low disturbance legs and with/without discs. A further plot was left undisturbed and fallow.

Two different cover crop techniques are being tested on the cultivated plots; a combi-drilled black oats/phacelia mix and a combination of black oats sown behind the loosening legs followed by broadcasted phacelia.

“We want to see if the latter approach helps black oat roots blast down the cracks and fissures, to hold them open for longer,” says Niall. “The phacelia provides a shallow, fibrous root system to condition the soil nearer the surface.”

All three areas have since been planted with spring wheat, where establishment, growth and yield will be judged and blackgrass levels assessed.

“Roots are the ultimate soil-conditioning solution, so we shouldn’t pass up the opportunity to use them.

“Through this work we’ll be able to show the best ways to move towards a low or no-till operation on these unforgiving soils, where roots are doing most of the work for us.”

Further work by David Purdy, PhD student and John Deere’s East Anglia territory manager, is aiming to collate and measure the benefits of good soil management.

“Over the course of Project Lamport, we’ve observed substantial physical improvements in the soil,” says Niall.

“Now we’re starting to measure them so we can provide objective advice in the future, giving growers even more confidence to implement the findings on their own farms.”

Using fully replicated trials, David will examine the impact of roots among a range of cover crop species with and without metal, in mixtures and on their own.

Compaction, soil density, visual assessment of soil structure, worm counts and organic matter levels are just a few of the numerous measurements that will be taken.

Further work on cover crops establishment is being carried out at Project Lamport. Residue management is a critical area. “We’ve tried direct drilling cover crops but without much success compared with the tried and tested method of power harrow/drill combination,” says Niall.

“However, the latter method undoes a lot of the good we are doing, so we’re looking at alternatives, including shallow discing to 2-3cm to mix in residues before using a direct drill. This has been a big improvement.

“We’re also looking at blowing cover crops into the previous standing cereal crop just before harvest. Where it established well there was no sign of any blackgrass, whereas even the shallow discing produced a carpet that emerged with the cover crop.”

This could also be a very useful tool to replace stale seedbeds, says Niall, and might also replace ploughing on some soils when setting out on the low- or no-till route.

“Ploughing is the generally accepted reset tool. But the standard of ploughing is not always sufficient to effectively bury all blackgrass seeds, and can turn up huge numbers of dormant seed. It might be better to leave the seed on the surface and let the cover crop start doing its work straight away.”

Blackgrass control at Lamport

Now entering its sixth year, trials at Project Lamport will continue to fine-tune cultural solutions to help growers tackle severe blackgrass infestations to best effect.

All the techniques will be on show this summer, with Agrovista staff on hand to talk through the findings in detail.

“Our main aim when we started out was to ensure customers with blackgrass problems could continue to grow profitable crops,” says Mark Hemmant, technical manager at Agrovista.

The site at Lamport was pretty typical of the East Midlands in terms of blackgrass issues, with extremely high infestation levels coupled with high resistance.

Research shows that the two most successful options for controlling blackgrass are rotational ploughing and using spring cropping in the rotation.

“Before the project started the field was ploughed,” says Mark. “The objective thereafter has been to leave nature to control the high population of buried very resistant blackgrass, whilst we minimise soil disturbance with the aim of depleting the weed seed-bank and minimising seed return.

“Under the farm’s winter wheat/oilseed rape rotation, blackgrass numbers were building up. So we decided to look at developing a system that would enable spring cropping.”

Over the past five years, Agrovista has been comparing 14 different rotational systems on farm-scale plots. These have included:

- Winter and spring cropping

- Autumn cover crops and spring wheat rotations

- Traditional fallows

- Hybrid rye for AD plants

- Winter wheat and OSR rotations

- Late-drilled winter wheat.

The most successful trial across the programme has used spring wheat following an autumn-sown cover or trap crop.

The cover crop needs to have sufficient enough biomass to condition heavy soil and pump out enough moisture over the winter to enable timely and reliable drilling. It also needs to be open enough early on to allow as much blackgrass as possible to come through, before being sprayed off ahead of spring drilling.

“We’ve found that a black oat-dominated mix has helped control blackgrass the best,” says Mark. “This species allows a low seed rate to be used to trap the grassweed; retaining an open growth habit early on, before putting on rapid growth both above and most importantly below ground later in the autumn.”

The cover crop, along with the ‘trapped’ blackgrass, is then sprayed off. The exact timing of this can make a real difference to the performance of the following crop, explains Mark.

“It’s crucial that the cover crop is desiccated in good time. In the first two years of the trial we carried this out six weeks before drilling and again a couple of weeks before. We’ve since found that applying the first spray around Christmas gives the best results in terms of spring cereal establishment and yield, while still delivering the benefits we want from the cover crop.”

Spring wheat is sown using a direct drill to minimise soil disturbance and therefore blackgrass chitting. “The more the soil is moved, the more the blackgrass grows.”

While the past few growing seasons have been very variable in terms of temperature and rainfall, the direct-drilled plots have consistently performed, delivering 8.3-10.6t/ha of spring wheat, similar to yields achieved in a winter wheat crop with a moderate blackgrass population.

“The blackgrass control has been so impressive that last season we only counted two heads/m² pre-harvest under this system,” says Mark.

Though there are often concerns over reduced yields by opting for a spring crop over a winter option, if blackgrass isn’t successfully controlled then this will put pressure on even the highest yielding winter crop, he adds.

“A winter wheat crop with a moderate blackgrass infestation won’t perform any better, costs more to grow and is exacerbating the blackgrass problem – each year it gets worse.

“Our rule of thumb is once head counts reach 40-50/m² you’re looking at serious yield loss in the following crop, if you don’t make significant changes.”

Other key work at Lamport on show this summer

- Depleting the blackgrass seed-bank – ongoing work at Project Lamport shows that spring cropping may have to be adopted for several consecutive years to control high populations of blackgrass on heavy-land farms.

- Environmental work – studies on wild flower margin management have been ramped up to help farmers optimise their response to future support payment requirements.

- Biologicals –examining the benefits of mycorrhiza inoculants (beneficial fungi that grow in association with plant roots) on plant nutrition and soil biology.

- Nutrition – is it is necessary to make up for the lack of soil N mineralisation under no-till systems?

- Flea beetle – to investigate indications that OSR establishment improves when companion crops are grown which may help reduce the impact of flea beetle damage.

Spring cropping on top for control

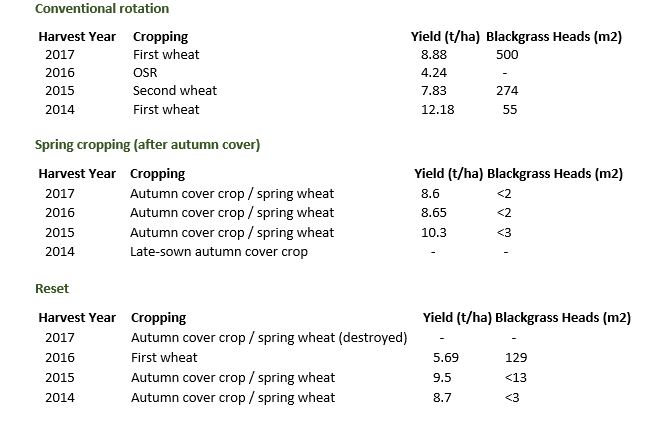

The effectiveness of spring cropping following autumn cover cropping compared with the conventional rotation and reset (ploughed) plots at the Lamport site shows that over the past four years this approach has consistently supressed the blackgrass population with minimal effect on yield.

Research Briefing

To help growers get the best out of technology used in the field, manufacturers continue to invest in R&D at every level, from the lab to extensive field trials. CPM Research Briefings provide not only the findings of recent research, but also an insight into the technology, to ensure a full understanding of how to optimise its use.

CPM would like to thank Agrovista for sponsoring this Research Briefing and for providing privileged access to staff and material used to help bring it together.

Agrovista is a leading supplier of agronomy advice, seed, crop protection products and precision farming services, whose roots were firmly established 60 years ago.

At Agrovista, we recognise that the face of agriculture is changing rapidly. Our aim is to equip growers with the tools they need to respond to these changes before they happen.

Through our extensive trials programme, we research and develop cost-effective and environmentally-sound crop solutions.