Cambs grower Hannah Derby has soils that don’t resemble any you’d find in small-plot trials, nor even on other farms. CPM visits to find out how that’s shaped her approach to on-farm trials.

With soils as unique as these, if you don’t do your own trials you never understand what works on your own farm.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

At the edge of the field, it looks as though someone’s emptied a small bag of compost into a neat heap. It is, in fact, a molehill, that illustrates the nature of this land – in a nation that struggles to reach 2% organic matter across much of its arable soils, this field has levels that exceed 40%.

So while most growers seek to build organic matter, Hannah Darby, who farms with her uncle, Tony, strives to manage the levels they have across some of the 360ha they farm, based at Sawtry, Cambs. “The soil is unique and the farm lies in a basin at around sea level. While the soil has its advantages, we struggle with issues, such as mildew, that few others do. Our farm is so different to anyone else’s we can’t rely on small-plot trials or other people’s results to know if something will work for us,” says Hannah.

Since returning to the family farm six years ago, Hannah’s set her course around a determined aim to understand the nature of the soils she has, and farm them to the best of their ability. This brought her last year to Real Results and a set of tramline trials in which the outcome, as well as the crop in general, were taken to new level of scientific scrutiny.

But it’s just the latest stage of the journey. “We started the reset in 2013, and over three years ploughed the farm to get on top of blackgrass. We’re now aiming just to direct drill and have also dropped oilseed rape from the rotation.”

The land comprises three units – the main home farm at Sawtry is where the high organic matter soils lie, while there’s heavier brick clay soils at Glatton and at Newborough. The move to direct drilling is as much as anything to keep the soil in its place, remarks Tony. “If you’re not careful, the wind can get up and you have to retrieve your field from the ditch at its edge.”

It’s the same with blackgrass, he notes. “Just the slightest movement of the surface creates a lot of disturbance with these fluffy soils.” So it’s a modified 6m Weaving drill that’s effectively now a GD model that establishes the crops, with its very low disturbance angled disc coulters.

The aim is to cut out cultivations altogether on land going into cereals, says Hannah. “We were cultivating to get rid of the straw and the land was drying out. We have used a straw rake but for this harvest have a new combine that will hopefully chop and distribute better.”

Leading discs on the drill touch the soil just enough to part the material in front of the coulters. “The more we’re doing this the more worms we’re getting,” she notes.

Cover crops are also helping here, as well as keeping soils in their place. Hannah’s moved to open out the rotation, which on the organic soils puts sugar beet one on six years with spring wheat, peas, spring oats and some land let out for potatoes, cropped around winter wheat. “Roughly half is in spring crops,” she says.

The peas are a good illustration of a crop she’s determined to master. “I spent a whole week combining last year’s off the floor and they yielded only 1t/ha. But they’ve got huge potential,” she maintains.

“This year we’re trying a tramline trial, planting oats as a companion crop with the peas. The oats will act as a trellis to help keep the peas standing and should take up some of the residual N, which will help with weeds that are our biggest problem.”

The inherent soil fertility in itself creates its own issues. “When the seed germinates it doesn’t have to go far to find nitrogen. That’s good for establishment, but means the roots don’t explore – we’re in an area with spectacularly low rainfall, so the crop needs a good root system to keep it going in the summer.”

Keen to explore the best way to deliver phosphate to the root zone, she undertook tramline trials in 2017 on spring oats. “Putting diammonium phosphate (DAP) down the spout at drilling worked best and resulted in a significant increase in biomass. Starter fertilisers such as Primary-P cost the same but DAP delivers more P and can be applied to the rooting zone,” she notes.

Hannah’s a strong believer that on-farm trials are a critical element to understanding her soil and discovering the best way to apply new ideas. “With soils as unique as these, if you don’t do you own trials you never understand what works on your own farm.”

And it’s something she’s brought from her previous profession. “I came into farming from physiotherapy, a job where you’re so close to research – you get journal access to latest developments, and it’s a matter of course to apply what you discover into your practice.

“That doesn’t happen in farming, but it should. And it ought to be a two-way process – farmers are such a diverse bunch with such a range of different situations in which we’re growing crops. True on-farm research is where the scientist gets to understand the complexity of what the farmer deals with and the farmer becomes more scientific,” she says.

A deeper understanding comes from Real Results

Last year was Hannah’s first as one of the 50 Real Results farmers. “I like to try things out, and what Real Results offers, through ADAS’ Agronomics approach, is to get more data about how crops perform in our very unique environment – that’s really appealing for us,” she says.

It was also a valuable chance to try an approach without chlorothalonil (CTL). “It’s a sad loss, and really worrying. Septoria isn’t the main disease threat here, but we routinely use it, so we’re keen to get a good idea of the difference it makes so we can plan for its withdrawal. We also submitted samples for Curacrop testing, where BASF give you an indication of latent infection.”

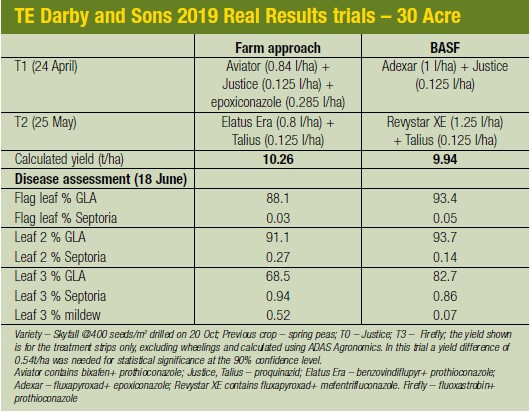

The field, known as 30 Acre, had come out of peas and was drilled with Skyfall winter wheat. With an organic matter over 40% and mildew the prime disease concern, it typifies the unique nature of the land Hannah and Tony manage.

It was also their first year of YEN, and Hannah was somewhat surprised that the theoretical yield potential of the field was calculated at 18.3t/ha. “I’m not sure ADAS’ estimate of yield potential really applies to us. The model works on sunlight and water availability, based on the depth of topsoil. Our soils are very deep, but just 50cm down you get to the peat layer that’s pH4.5. Roots don’t like to put themselves into that.”

A mildewicide was added into the mix at the first three spray timings – a standard practice across the farm, and one that adds considerably to the fungicide bill, notes Hannah. “This was the only wheat field that had two SDHIs, however, so we could get a good idea how the Adexar and Revystar XE programme performed next to our usual standard. For the rest of the farm, we decided this year that overall disease pressure early in the season didn’t warrant an SDHI at the T1 timing.

“Conditions by April were getting very dry and our crops were beginning to show signs of stress, so I think a lot of the crop potential had already been decided before the main fungicides went on. The nutrient testing also showed up boron deficiency – manganese is one we routinely apply as a foliar feed, but we’ve only ever worried about boron in sugar beet.”

Nevertheless, a disease assessment on 18 June showed up distinct differences. Septoria was the main disease found, with mildew still present on leaf three, especially in the farm-standard treatment. There was also a greater green leaf area (GLA) in the BASF-treated area, which was significantly higher on the lower leaves.

“The thing that interests me most is that the crop definitely stayed greener for longer in the BASF-treated area. The Revystar appeared to have an effect on the mildew too. I’m not sure we’d rely on it for mildew control, though, unless it was a definite low-mildew year.”

This difference in GLA was picked up in the NDVI image taken on 7 June,

), although due to cloud cover no images were obtained after this date. But the differences in GLA and disease control didn’t appear to come through at harvest. The north corner of the field yielded lower than the rest, so it was discarded from calculations to improve the precision of the analysis. The effect of the BASF treatment was actually to reduce the yield by 0.33t/ha, although this was not statistically different. A difference of 0.54t/ha would be needed for this, according to ADAS, with yield differences possibly attributable to other sources of variation, such as in the soil.

Hannah appears undaunted, however. “I think we will use Revystar, but probably just at one timing – we usually alternate product between timings anyway.” She favours the T2 timing, enthused by the effect on GLA and late disease, but Tony would opt for the T1 timing to get an early check on mildew and septoria.

“The Curacrop result was one aspect that surprised us – we had latent septoria in leaves that appeared completely free of disease when we took the samples,” notes Hannah. “It’s interesting that where we used CTL on the rest of the farm we got on average 0.5t/ha more than we did from the Real Results field. There may be a lot of septoria we’re missing.”

For this year, there’s been a switch to LG Skyscraper, mainly for its stronger mildew score, but also to get a better handle on applied N. “Last year we applied 149kgN/ha and an extra 40kgN/ha for protein. The level we achieved in the grain was 13.1%, but we don’t always succeed to get the milling spec. The residual N is currently at 250kgN/ha – far higher than most soils, and it’s currently causing us a problem, not an advantage. I’d like us to make greater use of an N-Tester to gauge exactly what the crop needs to build yield, making better use of the resources we have, and not worry about the extra N for grain protein.”

And it’s this level of detail from the Real Results trials that Hannah says has opened her eyes to what she feels she can achieve with her crop management. “When you have soils with unique qualities, anything that gives you real time feedback and a more scientific approach to how you manage your crop will pay dividends.”

The Real Results Circle

BASF’s Real Results Circle farmer-led trials are now in their third year. The initiative is focused on working with 50 farmers to conduct field-scale trials on their own farms using their own kit and management systems. The trials are all assessed using ADAS’ Agronomics tool which delivers statistical confidence to tramline, or field-wide treatment comparisons – an important part of Real Results.

In this series we follow the journey, thinking and results from farmers involved in the programme. The features also look at some in-depth related topics, such as SDHI performance and data capture and use.

We want farmers to share their knowledge and conduct on-farm trials. By coming together to face challenges as one, we can find out what really works and shape the future of UK agriculture.

To keep in touch with the progress of these growers and the trials, go to www.basfrealresults.co.uk