Whatever the worries about Brexit, there are few things in farming more gratifying than having a barn full of wheat. CPM visits a Suffolk grower to gather tips on how to achieve it.

A solid, hard Group 4 variety is one that will always deliver.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

As you wander through his wheat crop in late May, you can sense Jeremy Squirrell has a cool confidence in how it’ll perform. Whatever else may be going on in the world, he knows he’ll have a barn full of hard feed wheat by the end of harvest.

“This is good wheat-growing ground,” he says of his Beccles and Hanslope series heavy boulder clays. “Other crops will fall by the wayside, but we’ll carry on growing wheat. What’s more, there may not be much of an exportable surplus any longer, but there are plenty of chickens and pigs that need feeding. So a solid, hard Group 4 variety is one that will always deliver.”

The Beccles and Hanslope series heavy boulder clays make good wheat-growing ground.

With 340ha, based at Wattisham Hall near Stowmarket, Suffolk, KE Knock and Co has grown wheat for seed for over 30 years in a rotation that currently includes spring barley and winter or spring linseed and beans. Farm partner Jeremy’s focus on the hard Group 4 feed varieties makes him “Fit for the Future” – set up to grow wheat for a market with good prospects, and with a strategy for growing it that brings strong returns.

“The premium market in this part of the country is limited due to high transport costs, and we struggle to get a consistently high protein. But there are plenty of feed mills, so it makes sense to grow Group 3 and 4 wheats with yield potential, and focus on growing them well.”

For the past two years, Jeremy’s grown KWS Kerrin. “We were looking for a replacement for Reflection, and it seemed to tick a lot of boxes. It has KWS Santiago in its parentage, and it shows – the growth habit is reasonably similar with high tillering and high biomass, and it covers the ground well.

“On our heavy clay soils, we’re no longer drilling early because of blackgrass. So we need quite a forgiving variety that will tiller out if seedbeds are compromised. That’s what you get with Kerrin – we have areas with well over 900 tillers/m², which is comfortably more than the 600 tillers/m² we’re aiming for.”

To ensure a good crop, Jeremy’s first rule of thumb is to adapt the drilling to field conditions. “I’m a stickler for seedbed condition,” he says. “The advantage of our soils is that they’re self-structuring, but I’m trying to build the soil organic matter component – currently less than 2% – to help with water-holding capacity and nutrient availability. We’re rotating applications of compost around the farm, and most fields have now received around 50t/ha in total.”

Ground going into first wheat will generally receive a pass with a 3.5m Sumo Trio. This usually makes the ground suitable for one more pass with the farm’s Lemken Solitaire power-harrow combination drill. Second wheats are preceded by the plough and press.

“These days, we try not to drill before 20 Sept, but aim to have the wheats in the ground by the second week of Oct. We’ve had disasters trying to drill in late Oct before – once the land goes wet it never dries out.”

The seed is variably applied at a rate of 150-220kg/ha following soil survey maps prepared by Soyl. “We’re variably applying P and K and adjusting N applications according to leaf area index. We’re not manipulating the canopy as much with fertiliser as the seed, though, as it’s important to get the plants there in the first place.”

Establishment varies from 55-85%, and while the variable-rate seed helps even this out, he finds Kerrin also helps compensate with its tillering capacity. “Like Santiago, it’s quick to cover the ground well.

“In the spring, it’s slower off the mark than Reflection, for example, and has slow apical development like Santiago.”

As a member of the Stowmarket Yield Club, Jeremy has recently started tissue testing and takes regular tiller and plant counts to monitor growth and nutrient uptake through the season. “We do have a problem with nutrient lock-up. Currently we’re only applying manganese as a foliar feed, but as a group we’re carrying out on-farm trials across a range of micronutrients and this is an area where I can see there’s potential to increase plant biomass and yield potential.

“One thing the tissue tests have shown this year is that despite adequate applied nutrition, the plants are still short of sulphur. The levels of N in the plant are through the roof, though, so it raises more questions.” Last year, Doubletop provided the sulphur with the first dressing of N in the spring, while Nitraflo provided the other two N applications in liquid form. But this year, Jeremy’s switched to a liquid N/S blend for each dressing.

Timings, and getting these exactly right, form Jeremy’s second key aspect of getting the most out of a feed wheat. “For the first application, a second wheat gets slightly more N in the first dose and these are prioritised over a first wheat as soon as conditions allow in the spring,” he explains.

“It’s important to get nutrient round the roots as soon as possible and to get the N into the crop before the ground starts to go dry. So we’ll aim to get at least half the N on by the first week of April.”

This has to be played against lodging risk, however, and this is something that came slightly unstuck last year. “I think Kerrin’s place is as a second wheat, in less fertile situations. We did have a bit of lodging last year, although it was a bad season for it, so it would be wrong to jump to conclusions.”

Nevertheless, he’s raised the rate of Canopy applied this year at both the T0 and T1 spray timings. “I think the lodging was stem based, but we’ve given the crop both barrels to strengthen both roots and stem.”

The same care with rates and timings extends to fungicide applications. “We’re definitely not candidates for cutting corners when it comes to disease control. We were one of the first growers with Reflection and one of the first to discover its weakness on yellow rust. I don’t think we’ll have the same issue with Kerrin, but it’s taught us the value of early disease protection on a variety new to the market.”

So the wheats never go without a T0 application, generally based on an azole with CTL, and there’s an SDHI applied at both T1 and T2 timings. “I’ve heard the arguments around dropping to one SDHI, but you can’t accurately predict rainfall in the next 20 days and I’m convinced that prevention is better than cure for disease control and protecting yield.”

Although it starts its spring growth later, Jeremy reckons KWS Kerrin puts out its flag leaf slightly earlier than Santiago. “The difference is no more than two days, then it comes to harvest at about the same time. It’s a common trait with a lot of KWS varieties – they’ll put out the tillers, but then you have to keep them. If you do, they’ll have the potential to build biomass and hopefully, with the right weather, build yield as well.”

Another point he notes about Kerrin is its orange wheat blossom midge resistance. “That’s come in very handy this year as it’s been one of the worst seasons for midge here for at least a decade.”

His third key rule for getting the most from feed wheats is cleanliness, and he’s a “stickler” for rogueing out blackgrass and wild oats. “We spend as much on rogueing as we do on Hatra (iodosulfuron+ mesosulfuron), but with low seed return hopefully we get far better payback on rogueing three to four years down the line.

“As for the market, we always aim to go for varieties that we think growers will want. Kerrin has a lot going for it – there’ll be a great many changes over the next few years, but growers will always want a high-yielding Group 4 hard feed wheat that reliably fills the barn, and that’s what Kerrin does.”

Suffolk soils suited to the feed market

Based near Woodbridge, Suffolk, and trading throughout the eastern counties, 70-80% of the wheat seed sold by Walnes Seeds is sold as feed, according to managing director Andrew Cooper.

“The easiest haul is to the feed mills in this area, such as the large site at Bury St Edmunds, and growers in the region are very good at supplying that market. There are also the ports at Ipswich and Harwich,” he says.

“Growers zero in on varieties that show a consistent level of good performance. Primarily that’s down to yield – it has to be one of the top four or five on the AHDB Recommended List. But it should have a suitable disease rating with no weaknesses and good grain quality,” continues Andrew.

“KWS Kerrin fits right into those criteria, and has the added bonus of orange wheat blossom midge resistance, that’s become something of a talking point this year. On farm it’s proving very similar to Santiago, with high tillering vigour. The only aspect to note is that it needs careful management on fertile sites to avoid any problems with lodging.”

Like a number of leading varieties, Kerrin was caught out last year in some situations when wind and rain hit crops at just the wrong time, notes John Miles of KWS. “It’s a variety suited to the later drilling window and has the tillering ability that adapts to a slip in drilling or seedbed conditions.

“The aspect we’ve found with KWS Kerrin is that it has the consistency growers look for, and delivers that over a range of soil types. Like KWS Santiago, it responds to fungicide and you can push it for yield, but unlike its parent, it doesn’t require such a high spend, with no disease weaknesses. For growers for whom it’s all about feed, KWS Kerrin is one they can rely on to fill the barn,” he says.

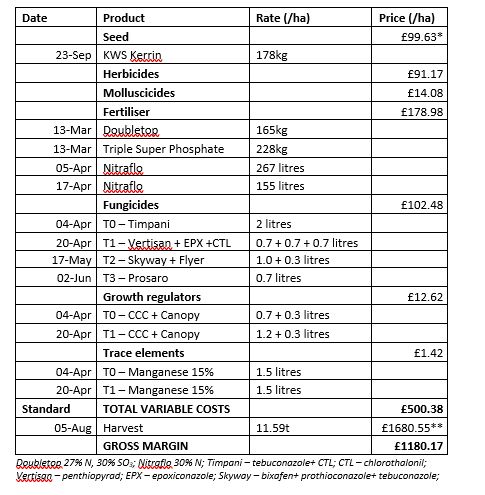

KE Knock’s recipe for Group 4 hard feed wheat, 2017

KWS Kerrin at a glance

Fit for the Future

As Brexit approaches, wheat growers will be preparing their enterprise for a market without the protection of the EU but potentially open to the opportunities of a wider world. Finding the right market, and the variety to fulfil it, will be crucial for those looking to get ahead.

In this series of articles, CPM has teamed up with KWS to explore how the wheat market may evolve from 2019 and beyond, and profile growers set to deliver ongoing profitability.

KWS is a leading breeder of cereals, oilseeds, sugar beet and maize. As a family-owned business, it is truly independent and entirely focussed on promoting success through the continual improvement of varieties with higher yields, strong disease and pest resistance, and excellent grain quality. We’re committed to your future just as much as you are.