In the first of a series profiling wheat markets with good prospects, and how to supply them, CPM travels to the Fens in search of a well thought-through strategy that ensures success with Group 3 wheats.

Other countries produce soft wheat, but it’s a completely different product – British Group 3 wheats are pretty unique.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

There’s a choice of biscuit to go with the tea on arrival at Arthur Markillie Farms, near Wisbech in the Fens: the ubiquitous Digestive is accompanied by a curious lozenge-shaped darker type, which, according to seven-year-old Felix Markillie, who’s presenting the options, “goes best with coffee”.

“In times of economic woe, us Brits will always turn to tea and biscuits,” notes his father, Sam Markillie, who picks a Digestive and duly dunks it. “Not only that, but we export them too, so they’re something of a success story.”

That’s one of the reasons he’s growing KWS Barrel, a high-yielding Group 3 wheat that attracts a premium for its suitability for the biscuit market. It makes him Fit for the Future – set up to grow wheat for a market with good prospects, and with a strategy for growing it that brings strong returns (see below).

But Sam’s no Brexiteer – European flags fly at the end of the farm drive and he has strong reservations about increased exposure to world trade. “Brexit may present opportunities, but there are clear threats: we’ll open up our markets to heavily subsidised imports and food produced at a lower cost of production that doesn’t meet the same high standards as our assurance schemes,” he points out.

“But I’m hopeful the brands we produce for can’t afford any slip-ups and won’t just ship in any old wheat from abroad. It makes relationships with end users so much more important – we have a number of these on our doorstep, and I want them to know I’m a producer they can trust for guaranteed quality and integrity from the tonnage I supply.”

They’ve grown milling wheats for many years on the 1000ha of Grade 2 silty clay loams, based at Trinity Hall Farm. The 600ha of wheat rotate around spring barley, oilseed rape, spring beans and 100ha of sugar beet. Alongside KWS Barrel are KWS Zyatt, Gallant and Cordiale.

“We always go for milling, partly because my old man said years ago that we’d never grow milling wheat. We have grown barn-fillers in the past, but there’s not much of a yield difference now, while there’s a considerable premium if you can get the quality and storage right.”

That initial doubt has now been well and truly kicked into touch – the farm achieved the Gold Award in the YEN inaugural Wheat Quality Competition from last year’s crop of Gallant. A 14.1ha field produced a 12.54t/ha crop with 13.4% protein, a Hagberg of 419 and a specific weight of 77.5kg/hl.

“We’re sponsored through the YEN by Hutchinsons and I find it worth its weight in gold in terms of the analysis it brings you on your wheat crop and the benchmarking with other growers,” remarks Sam.

So why’s he turned his attention to Group 3 wheats? “The beauty of Group 3 is the yield is comparable with a feed wheat, but you get the premium without the additional costs of getting the protein into the grain.”

It’s his third year with these soft wheats, and he’s turned from Zulu to KWS Barrel, grown initially last year and now entered as his YEN plot for harvest 2018. “The yield is very impressive, but it’s the standing ability that’s the winner,” notes Sam.

“That really came into its own last year when wheats just sat there in the dry and then took up a huge amount of N when moisture returned. Barrel’s stiff straw was probably worth 1.5t/ha over other varieties that lodged. It also has orange wheat blossom midge resistance and it’s later maturing, so fits in with our wheat portfolio.”

Grown as a first wheat, autumn cultivations start with a shallow discing from the 9.25m Väderstad Carrier, followed by the deeper tines of a 7.8m Väderstad Swift. A pass with a Cousins V-Form provides some soil loosening, while a new 7.5m Dalbo Rollomaximum forms the seedbed for the 6m Väderstad Rapid drill.

The crop tillers well in the autumn – no different to other varieties, notes Sam – and blackgrass is kept to a rogueable level. MOP and TSP were applied in the spring. “P and K indices are 2+ to 3, but not all of that is available to the crop,” he explains.

The early dressing of nitrogen was split, applied as a liquid with sulphur. “Solid sulphur was expensive last season, so we started with liquid, although the final N dressing was Extran to avoid the risk of scorch,” he says. “It’s good to have the choice of both solid and liquid fertiliser, and we consider more frequent applications to spread the risk – it’s important the crop doesn’t run short.”

The total applied N came to 207kgN/ha, with a foliar long-chained urea polymer applied at the T2 timing, designed to be a slow release of N to encourage the crop’s natural physiological response. By contrast, his Group 1 wheats receive a total of 276kgN/ha, with the extra N supplied through a late pre-T2 dose of Extran.

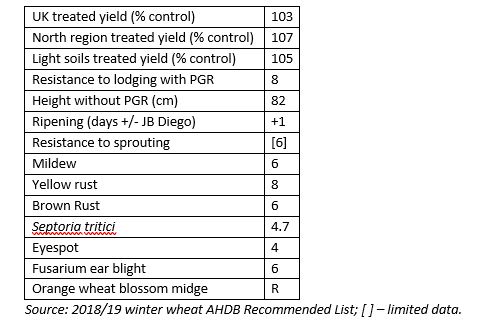

With a score for Septoria tritici of 4.7, according to the AHDB Recommended List, Sam recognises this is one aspect of KWS Barrel that needs to be managed. “But we manage the more susceptible varieties well here, and reckon a more robust strategy is to manage disease risk, rather than rely on varietal ratings. Spraying is all about timing and protection – it’s something we won’t compromise on, and we reap the rewards.”

Yellow rust tends to be a greater concern in the Fens, he adds. “Barrel has a score of 8, which is high enough to give you confidence, but not so high you’d feel it’s vulnerable to an unexpected change in rust populations.” A 5000-litre bowser and pre-mixer services the 36m Rogator sprayer and raises the productivity of the operation by 40%, Sam estimates.

There’s also a strategy at harvest, carried out with the farm’s New Holland CR9.90 with 10.5m header, and a John Deere C670i with 7.5m header. “We start with the Gallant, that’s always a week ahead, then harvest the Cordiale. Zyatt and Barrel come in later. We bring it into the barn as soon as it’s below 20%, pull the moisture down to 14-15% as quick as possible and then keep it cool.”

The farm built a brand-new grain store, completed two years ago. It represents an investment of £120 per stored tonne, and Sam finds it a valuable way to keep control of his marketing, which forms another strand of the strategy.

“As soon as I choose the variety, I offset the additional costs of meeting a quality wheat contract, such as any extra nitrogen and storage considerations, with a minimum premium, making sure I have a clear idea of the minimum margin I need. We sell through Fengrain and they offer a min/max contract for Group 3 wheats, which sets a base, but allows reasonable flexibility.

“Once it’s in the barn and quality known I can fix the premium separately to the base price. There is a cost to store, but the ability to condition and release grain when you choose is a great benefit when you’re producing quality wheats.”

Despite his strong strategic position, he’s not about to throw up another grain store, however. “I’m nervous about investing in the future. I have good connections with the trade, both in terms of how we source our inputs and sell what we produce. The key to securing our margins is to build on these relationships and engender more trust as we go through this period of uncertainty. How these develop will determine where we invest in the future,” notes Sam.

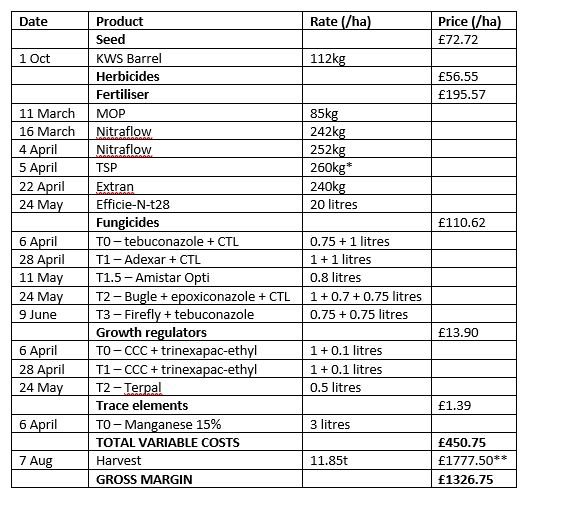

Arthur Markillie Farms’ recipe for biscuit wheats, 2017

MOP – 60% K2O; Nitraflow – 20% N, 12.5% SO3; TSP – 46% P2O5; Extran – 34.5% N; Efficie-N-t28 – 28% N; CTL – chlorothalonil; CCC – chlormequat; Adexar – epoxiconazole+ fluxapyroxad; Amistar Opti – azoxystrobin+ CTL; Bugle – epoxiconazole+ pyraclostrobin; Firefly – fluoxastrobin+ prothioconazole; Terpal – mepiquat chloride+ 2-chloroethylphosphonic acid; *applied on four-year rotation, so cost split accordingly; **based on ex-farm price of £150/t

How the UK crop takes the biscuit

Both current stats and the views of millers suggest the UK biscuit wheat market is one that looks fit for the future. There were an estimated 1.6M tonnes of Group 3 and 4 soft wheats available to millers from the 2017 harvest. This feeds a domestic flour demand of around 1.1M tonnes of wheat – biscuit wheat alone accounts for 670,000t – leaving a net balance of less than 500,000t.

But soft wheat availability has fallen considerably – in 2011 the net balance was more than 2.5M tonnes – leaving millers wondering what would happen if a poor harvest was to hit available supplies. Within this, Group 3 varieties account for just a third of soft wheat plantings – a paltry 6% of the total UK wheat area.

On the demand side, domestic sales of sweet biscuits are rising steadily, up 2.3% year on year in 2017 to £1.7bn, according to market analyst Mintel. But there’s a growing demand for British biscuits abroad – they’re in the top 15 food and drink exports, according to Defra, and were worth £390M in 2015 (not including savoury biscuits). United Biscuits, that includes McVitie’s, Carr’s and Jacob’s brands, reported a 50% jump in exports over three years to 2015. The manufacturer’s parent company Pladis is predicting a further 50% rise by 2020, focusing on the Middle East, Africa and the US.

It’s a product that only British growers can supply the wheat for, notes David Elderkin, senior trader at Fengrain. “Other countries produce soft wheat, but it’s a completely different product – British Group 3 wheats are pretty unique.

“They have a particular gluten quality, functionality and baking ability. If you think about a Digestive or Rich Tea biscuit, every single one has to be the same size and fit perfectly when stacked and wrapped,” he explains.

The Fengrain contract offers a minimum £10/t premium for Group 3 soft wheat meeting at least 10.7% protein, 130 Hagberg and 74kg/hl specific weight. “Sam’s a good grower because he does his numbers and puts thought into his strategy. He’s growing for a market and knows what it wants, and he can get the yield,” notes David.

The market has potential to grow, he adds. “We can’t import for it, which is why manufacturers support the home-grown product, with the help of breeders like KWS bringing on strong varieties. They’ve got the yield and it’s a local market, so there’s every reason to grow for it.”

KWS Barrel is a cross of Viscount with Bantam, says product development manager John Miles. “Bantam was an early sower, utilising Xi-19 in its parentage while Viscount was fantastic for physical grain quality, performing well on light land and in the North.”

Barrel carries these performance characteristics through, with a yield score of 107 in the North and 105 on light soils, according to the RL, although it’s well suited to a later drilling window, he points out. “It’s also one of the stiffest on the RL.”

In the spring, it behaves like KWS Santiago. “Barrel’s slow to get started, but once it does, it’s vigorous. It’s a variety you can push for yield, provided it’s got the tillers. That means plenty of early N, particularly if the crop was late drilled.”

The Septoria tritici score is the variety’s weakness. “It needs good husbandry, particularly in bad septoria areas, and will respond well to a robust spray programme applied at the right timings.

“At harvest, it’s middle of the pack on maturity and has a robust grain quality – it doesn’t sprout like Viscount – although you should never leave a quality wheat out in the field for too long. Push KWS Barrel for yield, look after it, and it’ll perform for you,” concludes John.

KWS Barrel at a glance

Fit for the Future

As Brexit approaches, wheat growers will be preparing their enterprise for a market without the protection of the EU but potentially open to the opportunities of a wider world. Finding the right market, and the variety to fulfil it, will be crucial for those looking to get ahead.

In this series of articles, CPM has teamed up with KWS to explore how the wheat market may evolve from 2019 and beyond, and profile growers set to deliver ongoing profitability.

KWS is a leading breeder of cereals, oilseeds, sugar beet and maize. As a family-owned business, it is truly independent and entirely focussed on promoting success through the continual improvement of varieties with higher yields, strong disease and pest resistance, and excellent grain quality. We’re committed to your future just as much as you are.