On the crest of a boom, there’s cautious optimism for Scotland’s distilling industry, and newer varieties are ensuring the genetics are available to farms across the UK to supply it. CPM visits two Scottish growers for whom KWS Sassy is a now a mainstay.

It’s not often you get all your cherries in a row.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

It’s early August and parts of Scotland have just received some of the heaviest downpours of rain experienced in months. While flooding has caused disruption to public transport and made some roads unpassable, there’s water puddling in the tramlines of Bruce Christie’s spring barley crop, and just a week or two from harvest, the ground is unnervingly soft underfoot.

But Bruce appears unfazed. He’s looking across the golden, remarkably even and upright crop of KWS Sassy, boasting some pretty impressive ears, and there’s a note of anticipation in his voice. “It’s our third year with this variety and it’s been yielding over 7.5t/ha – that’s exceptional for us,” he says.

“We don’t grow a variety for its own sake, but like to try one on our own soils and if it performs, it makes the AHDB Recommended List almost irrelevant.”

Burghill Farms form part of the Dalhousie Estate that stretches across 13,000ha of hill land in Glen Esk, and another 1000ha of arable crops, based at Brechin, Angus. Most of the cropping lies at 50m above sea level, farmed alongside a 100-head herd of Aberdeen Angus beef cattle and 1500 ewes, with progeny sold as stores. 200ha of spring barley currently comprises KWS Sassy grown alongside Laureate and LG Diablo. The wheat crop is of similar size, with winter oilseed rape and land rented out for potatoes, carrots and vining peas providing the breaks across the gravelly to medium-loam soils.

“The arable side of the business shows a small profit before the Single Farm Payment,” reports farm manager Bruce. “We’ve always grown spring barley and the crop’s as profitable as wheat – there are more pluses than minuses with it. It supplies a booming local market and it’s one we should be growing for, but we can’t be too reliant on it, and the weather is always a concern. Looking ahead, the price is also a worry – with support payments dropping away, can we cope when the market fluctuates from £120-170/t?”

With the malting barley grown under contract for WN Lindsay, Bruce uses futures to hedge against the worst of the market swings. Until two years ago, Concerto was the main variety. “We tried a field of Sassy in 2017 and then it became a mainstream variety last year,” he says.

“Concerto was always reliable, but it was becoming outclassed in yield terms. That showed up last harvest with Laureate and Sassy both performing well at 7.7t/ha and 7.5t/ha respectively. But Concerto was around 0.6t/ha lower.”

Spring barley follows wheat, and the farm only grows first wheats. “Generally, every field is ploughed, unless it’s coming out of potatoes. We drill in March/April with a 4m Amazone Avant power-harrow combination drill – this allows us to go in a wider window of soil type and condition.”

Diammonium phosphate (DAP) is fed down with the seed, supplied through a front-mounted hopper. “It’s good to put the P close to the seed – that way it ensures it reaches its potential.”

It’s a practice recommended by Ian Simpson, Bruce’s local trader with WN Lindsay. “A lot of growers had moved away from putting fertiliser with the seed, but are now coming back and with spring barley in particular, there is a noticeable benefit,” he says.

While the seed rate Bruce aims for is 190kg/ha, he’s noticed he’s had to take account of thousand grain weight with KWS Sassy, which comes in as high as 55g. “We’re aiming for an established population of around 300 seeds/m² and our soil type varies, so we variably apply the seed. With Sassy, the bolder grain means a higher application rate in terms of kg/ha, but the variety tillers well, so you end up with a good even establishment.”

Bruce’s philosophy with the crop is to feed its potential. “We’re focused on optimising cost per tonne, rather than saving cost per ha. So we use two SDHIs, and I believe the early one helps to regulate the growth, too. We don’t use chlormequat, but always apply a late dose of Cerone, which I believe is a very cost-effective insurance against lodging.”

Liquid fertiliser keeps applications accurate, he reckons, and sulphur is an essential addition. He finds he’s putting a little more N on his spring barley these days, but the growth of the crop warrants it, provided it’s regulated, and grain N remains within spec. A trace element programme, including manganese in particular, ensures the crop has everything it needs to reach its potential, he says.

“Some may say a three-spray fungicide programme for spring barley is excessive, and we’ll only apply an early dose if it’s warranted. But the growing season for the crop is so short – before you know it, it’s all over. So we try as hard as possible to keep the timings right, and find that a little extra spent on looking after a variety like Sassy usually rewards you.”

Benefits build

Only a sturdy 4×4 gets around Ian McHattie’s farm, near Elgin, east of Inverness following the previous night’s rain – it’s washed great boulders down the slopes of his tracks, but in the field, his crop of KWS Sassy looks remarkably unscathed. “55mm has fallen in the past three days, and we had 30mm just last night, but we have ideal land here for malting barley, if the weather’s right,” he says.

Based at Newfield Farm on the Black Hills Estate, Ian farms 300ha of cereals with a further 80ha of grassland on sandy loam soil, within a relatively narrow, predominantly arable strip near the Moray coast. Most of his land lies 50-100m above sea level with an average annual rainfall of around 600mm.

Spring barley is the main arable crop, grown in rotation with land let out for potatoes and carrots, with just 30ha of wheat. KWS Sassy was grown for the first time in 2017, and the area’s grown to 164ha in the ground for 2019 harvest, alongside Chronicle and a small area of Concerto.

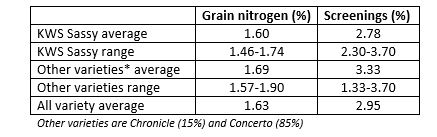

“First of all there’s the yield, with KWS Sassy averaging 0.6t/ha more than the all variety average,” notes Ian. “Then there’s the quality – Sassy delivers a nice bold sample with lower nitrogen and screenings than the others. Then there’s also straw yield, with Concerto achieving about 75% of what we get from Sassy and Chronicle. It’s not often you get all your cherries in a row.”

Straw is an important commodity in Ian’s part of Scotland, where farming turns predominantly livestock once you move further inland, while carrots take 100 Heston bales on every ha. “Straw is worth the equivalent of an extra 1.25t/ha of grain yield. With the Sassy, it’s like you’ve cut a field of winter barley with the straw yield you get,” says Ian.

Care’s taken to keep this standing, and while one PGR usually suffices on his light land, some of the crop was planted after stubble turnips this year and received two doses.

Land in front of spring barley is ploughed and pressed, with April being the drilling month, handled by a 4m Väderstad Spirit combination grain and fertiliser drill. “You need a good seedbed, and our biggest concern is moisture. We like a dry spring as it encourages roots to chase the moisture down, although last year it did turn worryingly dry.”

He raised his seed rate from 190kg/ha to 210kg/ha this year to deliver the target 370-380 seeds/m², on advice from Scotgrain’s Ian Abbott. “Sassy’s noticeable bolder grain means a higher thousand grain weight. We supply seed dressed with manganese, copper and zinc, and Cu in particular is one to watch in this area,” he says.

“Phosphate isn’t such an issue on Ian’s soils, but sulphur is, which is why we recommend a fertiliser with a sulphur content at drilling and at top dressing.”

These applications complement a fairly healthy coverage of farmyard manure. “It’s the kind of ground you could throw straw and dung at for ever and it’ll never get enough,” notes Ian McHattie. His two-spray fungicide programme is based on strobilurins, with CTL added at the T2 timing for ramularia.

Come harvest, aside from the grain and straw yield, it’s the sample from Sassy that Ian notes. “I do like bold varieties. They not only deliver you a higher yield with lower screenings, it dilutes the grain N, and the Sassy average is notably lower than the others. Spring barley is a crop that does well for us, and Sassy is likely to remain our mainstay variety.”

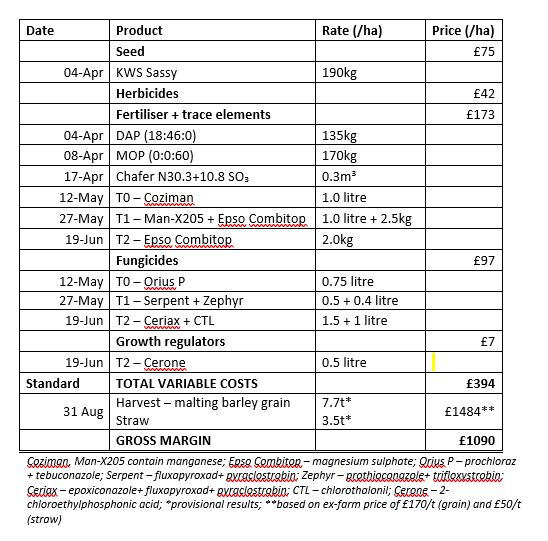

Burghill Farms’ programme for spring malting barley, 2019

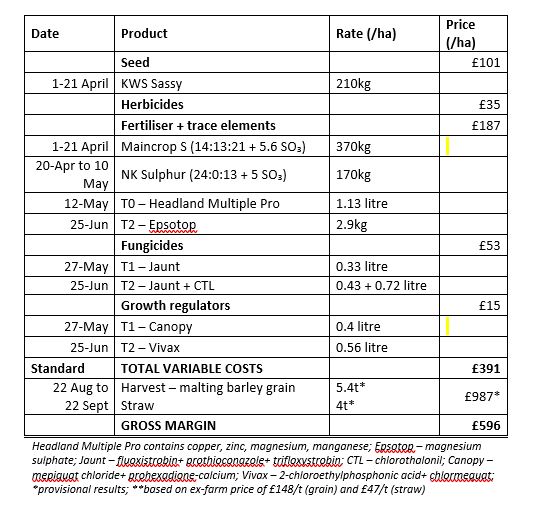

Newfield Farm’s programme for spring malting barley, 2019

Assessing the Sassy sample (Newfield Farm results, 2018)

Brexit set to brighten British barley’s boomtime in distilling

With all the uncertainties facing cereals and oilseeds, malting barley for distilling is one commodity with an arguably strong future, and not just for Scottish growers. But like all cereals, future arrangements over tariffs and trade agreements will affect the market, while uncertainty for related food and drink products, particularly whisky, could have an impact.

It’s the Scottish distilling industry that keeps the market buoyant for home-grown malting barley. The latest figures from HM Revenue and Customs put 2018 exports of Scotch whisky at £4.7bn – by far the UK’s leading food and drink export. With a value to the UK Exchequer more than six times the next biggest food export, this likely lends Scotch whisky strategic and political importance, especially as exports to the US have just risen over £1bn for the first time.

But the industry is currently reeling following a decision by the US to impose a 25% tariff on Scotch whisky later this month. While it’s too early to call the likely impact, the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA), said the industry has been “hit hard”, and also underlined grave warnings of “cost and complexity” issues from a no-deal exit from the EU. Exports of whisky to the trading bloc account for 30% of the total, with France the biggest export market by volume.

Koshir Kassie from Boortmalt confirms Brexit is high on the whisky agenda. “But it’s an interesting time for the malt market – a lot of people across the world are trying new things and looking to find something different. This opens up a number of opportunities in both Scotland and England.”

Boortmalt is the fifth largest maltster globally and is just about to take over Cargills’ malting business. It’s also the largest UK maltster, processing over 300,000t annually, with two plants in Scotland, one in N Yorks and one in Bury St Edmunds. Koshir believes the malt market will be generally unaffected by Brexit, with the largest impact potentially for the Scotch whisky market. “The vast majority of UK exports lie outside Europe, and there’s a lot of interest in Scotch as well as English malt, particularly in the Far East for distilling and in the growing global craft markets.”

According to AHDB, around 200-300,000t of malting barley are exported annually, mostly from the south coast or within the island of Ireland. The UK is a net exporter of malt, with nearly all imports coming from the EU and 91% of exports going further afield.

AHDB’s analysis of the likely effect of Brexit on malting barley prices suggests these would be largely unaffected if a free-trade agreement is secured with the EU. If the UK retains tariff-free imports but EU exports are subject to tariffs, the export price for both malting barley and malt could fall by up to 8%. The effect of mutual application of tariffs is likely to hit malt imports hardest as it carries a €152/t tariff into the EU. So the overall impact on prices is likely to be minimal, although it could affect premiums, at least in the short term, says AHDB.

In Scotland, the market for malt has been expanding, with 29 new distilleries constructed since 2004 and many existing ones adding capacity. WN Lindsay is the biggest procurer of malting barley in the country, taking in around 216,000t annually to its three sites at Gladsmuir Granary, Trannet; North Esk Granary, Stracathro; and Fife Park Granary, Keith.

“Predominantly we’re supplying Diageo and Boortmalt, taking direct from growers at harvest and drying down to 12%,” explains seeds manager Peter Gray. “The market is currently strong, and Scottish growers are particularly well placed to supply it – they benefit from the longer day length during ripening and have the buyers right on their doorstep.”

The required spec from distillers is maximum 1.65% grain nitrogen, minimum 98% germination with at least 90% of grain retained on a 2.5mm sieve. “The benchmark was Concerto, and it still is to a certain extent,” continues Peter. “But it’s becoming outclassed and we’re now favouring Laureate, LG Diablo and KWS Sassy for their higher yield. These three are not wildly different and it’s largely down to the individual grower as to which comes out best.

“Sassy matures earlier than Diablo and agronomically stacks up better than Laureate. On paper its yield may not be as strong as its rivals, but the difference is in the quality, and in particular the shape of the grain – Sassy gives a good, bold sample.”

Bairds Malt has an intake to its four Scottish plants of just over 200,000t, with a new facility at Arbroath alone putting 57,000t of malt on the market annually. Smaller plants are located at Inverness, Turriff and Pencaitland, east of Edinburgh. “Ultimately we’re looking for a high spirit yield from a malting barley variety, but it has to perform for the grower, too,” notes Ian Abbott of Bairds subsidiary Scotgrain.

“We’re also looking for consistency. What we like about KWS Sassy is that it produces a good, bold sample with low nitrogen and low skinning levels, even in more challenging years. Concerto has been the market standard, but now it’s going off the boil. Farmers have newer varieties that perform better both in terms of yield and agronomically.”

The opportunities with KWS Sassy lie not just with Scottish growers, though, says Koshir. “We like the variety because it has one of the highest predicted spirit yields and a high specific weight. Being a purely distilling variety it also focuses the farmer and ensures we get a more consistent intake. It’s hardly grown at all in England, though, and we’d welcome the opportunity to develop the market for it.”

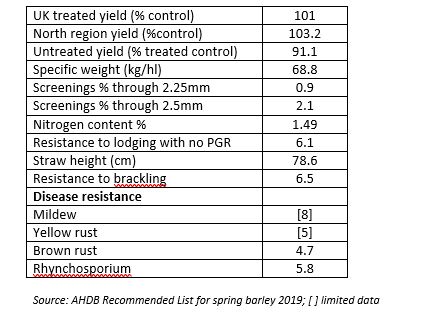

A cross of Concerto with Publican, KWS Sassy is a non GN-producing spring barley variety with full MBC approval for malt distilling use. It has the lowest screenings on the AHDB Recommended spring barley List, among the highest scores for rhynchosporium, with a hot water extract that equals Concerto. Its maturity is on a par with the benchmark variety, says KWS, while Sassy’s yield is about 11% higher in the North.

KWS Sassy at a glance

Fit for the Future

As Britain exits the EU, wheat growers will be preparing their enterprise for a market with less protection, but potentially open to the opportunities of a wider world. Finding the right market, and the variety to fulfil it, will be crucial for those looking to get ahead.

In this series of articles, CPM has teamed up with KWS to explore how the wheat market may evolve, and profile growers set to deliver ongoing profitability.

KWS is a leading breeder of cereals, oilseeds, sugar beet and maize. As a family-owned business, it is truly independent and entirely focussed on promoting success through the continual improvement of varieties with higher yields, strong disease and pest resistance, and excellent grain quality. We’re committed to your future just as much as you are.