Yellow rust has been becoming increasingly genetically diverse in recent years and behaving in an unpredictable way in the field. CPM finds out the latest developments in its rapidly shifting population.

The red group are outcompeting the blue group (Warrior 3).

By Lucy de la Pasture

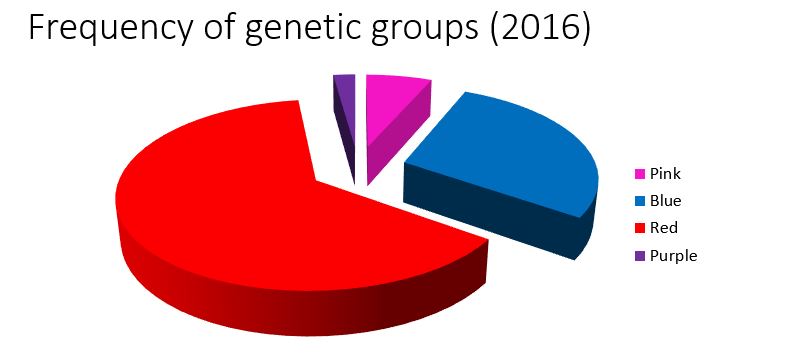

The struggle between the different pathotypes of yellow rust appeared to settle down in 2017, with the red group of isolates well and truly winning the war, according to the results presented at the UK Cereal Pathogens Virulence Survey (UKCPVS) Stakeholders meeting last month.

“The frequency of red isolates has increased to over 90% of the isolates tested in 2017, a rise from just over 60% the previous year.” explains UKCVPS project manager Dr Sarah Holdgate, based at NIAB in Cambs.

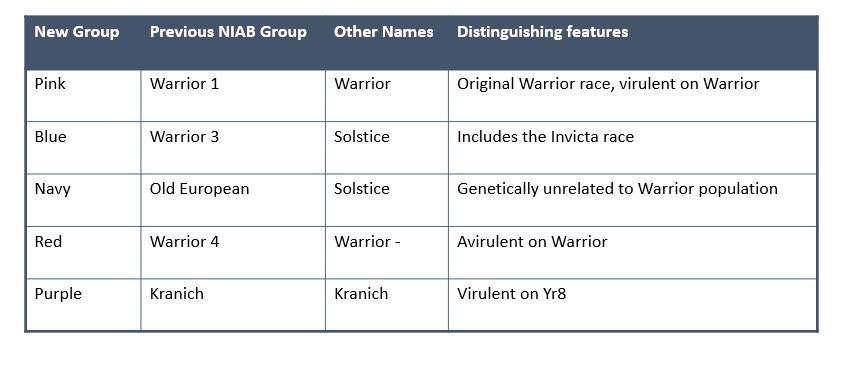

The red group of isolates was previously known as Warrior 4 or Warrior minus prior to the introduction of the new naming system last year. The new classification was devised to cope with the growing genetic diversity of the yellow rust population.

“Before 2016, the Warrior 4 pathotypes were characterised by being avirulent to the variety Warrior. In the yellow rust epidemic of 2016 there was an incursion of new isolates which were similar in virulence to the old Warrior 4 grouping, apart from the fact they all carried virulence to Warrior,” explains Sarah.

The new naming system reflects both the race and genotypes of the isolates, so they can be more easily grouped together but separated into subgroups of isolates, such as Red 5, Red 11 and Red 24, in the absence of complete virulence data.

In 2017, Red 24 was the most common isolate found, present in 36% of samples which is unusually high, reflects Sarah. Newly detected isolates also appear to be thriving, with one of the five newbies, Red 28, representing 29% of the isolated tested.

“The red group are outcompeting the blue group (Warrior 3) and we had no detections from either the pink (Warrior 1) or purple (Kranich) groups last season. Isolates from the blue group didn’t include the Blue 7, which like Red 24, was one of the causal groups of isolates behind the 2016 epidemic.

“Work is underway to establish if Red 24 isolates are outcompeting other isolates. It’s important to understand the make-up of the yellow rust population to understand the impact on varieties. For example, Red 24 is relatively damaging compared to other isolates and its continued presence in the UK is not welcome news,” she comments.

“Over the 2016-2017 winter, there were several frosts, something that hasn’t been experienced since the incursion, and it’s also possible that some of the other groups suffered a fitness penalty and consequently crashed in the population,” she suggests.

In addition to Red 28, further new isolates were found – Red 27, Red 29, Red 30 and an unnamed isolate.

These new isolates are interesting because, according to seedling tests, the additional virulence they carry makes them similar to other isolates found in previous years. For example, Red 28 has the same pathotype as Red 11, except it also has virulence to the variety Evolution. Similarly Red 5 is identical to Red 27 other than the new isolate also has virulence to Evolution.

“Red 29 and the unnamed isolate have very complex pathotypes meaning that there are lots of varieties and resistance genes that they can overcome. They are similar to isolates in the red and pink groups but again have additional varietal virulences, with Crusoe in common (see table). It’s important to highlight that in Crusoe, adult plant resistance remains robust.

“Red 30 is notable because it doesn’t carry virulence for the plant resistance gene Yr1. It has a very similar pathotype to an isolate found in North Africa and Europe (named PstS14) which caused widespread epidemics in Morocco last year,” she explains.

Sarah confirms that Red 28, Red 30, Red 24, Red 26 and the unnamed isolate will all be going forward into adult plant trials in 2018 so that their potential impact in the field can be tested.

“At first sight 2017 seemed to be a quiet year but when you look at what’s happening to the population in depth, the situation is still changing and remains utterly unpredictable,” she concludes.

Yellow rust groups as proportion of the population tested.

The red group has increased at the expense of the other groups of isolates in 2017 (right) compared with 2016 (left).

Source: UKCPVS

Rustwatch

A new four-year EU-funded project called ‘Rustwatch’ was also announced at the event. Led by the Global Rust Reference Centre in Denmark, the project will monitor rusts across Europe and develop a coordinated early warning system.

As part of Rustwatch, people are being asked to extend their monitoring and sampling beyond cereal crops to include the alternative host – common barberry (Berberis vulgaris). The hedgerow plant is of interest because it’s where the sexual cycle of the yellow rust pathogen takes place and Sarah is keen to receive location information where the barberry plant is spotted.

“We don’t think that yellow rust is reproducing sexually in the UK, but we can’t be sure, but this project will enable us to find out. To do this we need to establish where the plant is located in close proximity to arable fields, which is most likely to be in old hedgerows,” says Sarah.

At John Innes Institute, crop geneticist Dr Diane Saunders is looking to establish whether stem rust could become re-established in the UK. It’s a disease that used to be widespread but is now rarely found, with the last recorded incidence in this country in 2013, where it was found to be infecting a single wheat plant.

“There have been an increasing number of outbreaks of wheat stem rust across western Europe, notably since 2013 in Germany, Sicily and Sweden,” she explains.

The common barberry plant is again coming under the spotlight as it also acts as the alternate host for wheat stem rust, allowing completion of the sexual phase of its lifecycle.

Members of the UKCPVS audience voiced scepticism that stem rust would ever re-establish as a major disease in the UK. It was pointed out that more than 98% of the wheat area is sprayed with fungicides which have good activity on the rusts. Stem rust also prefers hot, dry conditions which is something the UK isn’t renowned for and there was a view that even with climate change, it’s unlikely that we’ll see any major epidemic in our lifetime.

Diane, on the other hand, believes that it’s not prudent to bet against the pathogen. “Because of the increase in incidences in western Europe and the fact that stem rust has been shown to be undergoing sexual reproduction in Sweden, pathotypes could arise that would be able to grow in our climate,” she says.

“With greater than 80% of UK wheat varieties shown to be susceptible to a UK stem rust isolate we tested, fungicide application would be the major control measure. And as we know with yellow rust, fungicides are very effective, but we can still experience significant losses in epidemic years,” she says.

Brown rust threat remains

Independent agronomist Tristan Gibbs, working in Kent and East Sussex, is advising wheat growers to remain vigilant for attacks of brown rust this season.

“Be particularly watchful if growing some of the popular newer quality wheats with lower brown rust resistance ratings, especially if sown early,” he urges.

“Brown rust is usually a mid to late summer, hot weather, high humidity disease. In the south east we can experience slightly higher temperatures, especially later in the season. If a brown rust epidemic is combined with drought, it can really take green leaf area out.

“Mild winters will allow brown rust to build to higher levels during the spring, allowing populations to cycle quickly in the next hot weather event, so we’d prefer to have cold winters with multiple frosts. Depending on variety, we normally don’t need to do anything about it until T2.”

The relatively hard winter we’ve experienced hasn’t knocked brown rust on the head. Tristan says pustules of brown rust were visible in mid-March on Crusoe, despite hard frosts that swept the country a week or so earlier.

Examples of quality wheats that he’s planning to keep a watchful eye on include Group 1 Crusoe; Group 2’s KWS Siskin, KWS Lili and Cordiale and Group 3’s KWS Basset, Zulu and Claire.

“There are more growers with Siskin this year. It’s the new kid on the block, but it’s only a five for brown rust. It’s a high-yielding variety, however, and very clean for septoria, so Siskin can be a lower input crop.”

To head off late-season brown rust, Tristan advises considering a robust T2 and T3. “If you cut back on fungicide rates, protection can run out of steam before the plant has started to naturally senesce. For susceptible varieties you need to make sure you have enough persistency from an SDHI and triazole rates at T2, and a strobilurin and triazole at T3.”

After gaining experience with Syngenta’s new SDHI treatment Elatus Era (benzovindiflupyr+ prothioconazole) in a brown rust situation, in both trial plots and commercial use last year, he says on susceptible varieties, it’ll be his T2 choice.

“There was a noticeable difference in brown rust control with Elatus Era – even versus other SDHI plus azole mixtures in the trial. It seemed more persistent and didn’t need a strobilurin at T3 in the trial plots. So this year, I’ll be trying to reduce input costs by not using a strobilurin at T3 on rust-prone varieties,” he adds.

According to Syngenta field technical manager, Iain Hamilton, although brown rust is at its peak risk anywhere south of a line from the Wash down to the Severn, growers can’t afford complacency even further north.

“Some of the feed wheats, which may have been chosen more for their septoria resistance, have only moderate brown rust resistance. So check your varieties’ ratings. Brown rust isn’t far behind yellow rust for potential yield loss, and you don’t want it to slip in under the radar,” says Iain.

“We knew Elatus Era was good on brown rust, but last year showed how good it was, including persistency. Those who used Elatus Era at T2 found they were less likely to need a follow-up treatment for brown rust compared with other treatments.”

Mildew matters

The UKCPVS brought some good news where mildew is concerned. In spite of a relatively high-pressure season in 2017 and an increased number of samples received, there were no nasty surprises to report.

“For wheat powdery mildew, there was an increase in virulence frequencies for most resistance genes but there were no significant reports of any resistance breakdown in the field,” says Sarah.

As far as barley powdery mildew is concerned, all pathotypes remained at a high level in the population. But virulence frequencies were generally stable, with some increasing and others decreasing slightly.

“The virulence for mlo-11 continued to rise and mlo-Riv was detected for the first time since 2013. More than half the spring barley varieties have the mlo-resistance genes, so there’s intense selection pressure for these pathotypes. Even so there were no reports of unexpected disease in crops,” she adds.