With uncertainty over Vydate production, trials looking at biofumigant cover crops are proving their worth. CPM reports on results, along with the latest on blight and early weed control.

proving their worth. CPM reports on results, along with the latest on blight and early weed control.

By Lucy de la Pasture

Many growers are facing a leap into the unknown this season in the absence of Vydate (oxamyl). With a degree of uncertainty whether the production of Vydate granules will ever resume, it’s a good time to look at the alternative measures to help keep nematode populations at a manageable level.

One of those measures is growing a biofumigant cover crop and it’s something to consider now to be time for next season’s potato fields. Trials carried out by RAGT and Agrovista suggest that they could play an important role in controlling free-living nematodes (FLN).

Their trial site at Elgin on the Moray Firth is under organic production on a farm that has suffered high FLN counts, says Agrovista agronomist Andy Steven. “Spraing, the disease caused by the tobacco rattle virus transmitted by FLN, is a fairly common problem here and on other lighter soils in Morayshire. Around half the samples show high FLN counts.”

Chopped and incorporate

The site was split into five sections – one untreated and four areas each planted with a different biofumigant crop – oilseed radish, white mustard, Hardy Mix (a blend of oilseed radish, Ethiopian mustard and rocket) and Japanese oats. These were drilled in late July to ensure there was plenty of biomass to be chopped and incorporated in mid-Nov.

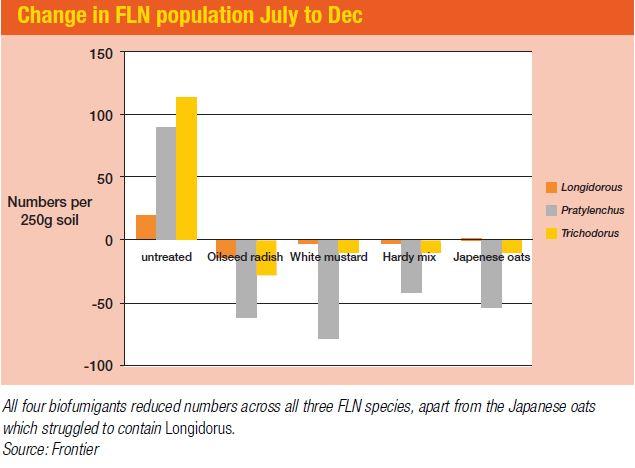

Nematode numbers on the untreated area went up “pretty significantly” between June and Nov, particularly Pratylenchus and Trichodorus species, Andy Steven says. “This would normally be expected as soils become wetter in the autumn, encouraging nematodes to move upwards through the soil profile.”

Numbers of these two species were higher than the treated strips to begin with and reached proportions where a nematicide would need to be given serious consideration, he adds. Longidorus was also present but the population was much smaller.

“We can’t say statistically that everything worked better – the Hardy Mix and the Japanese oats worked reasonably well. But in this trial at least, the oilseed radish did the best job and white mustard came a good second,” he says.

Oilseed radish provided the best control of Longidorus and Trichodorus, while white mustard had the edge on Pratylenchus. The results suggest that targeting different species of nematode with specific biofumigant crops may help further and is likely to be a key focus of future trials, says Andy Steven.

If these results were repeated in the field, he predicts significantly less feeding damage as well as potential disease reduction. “Growers in this area have achieved a 10t/ha yield increase where feeding damage has been reduced. Potatoes will be planted across the trial site so we’ll be able to measure this effect.”

Mild climate

The trials also show it’s possible to establish biofumigant crops in the far north of the UK, albeit in a relatively mild climate. “A big challenge in this area is getting a cover crop established in time to provide enough green material for it to work. In practice it might be best to plant biofumigant crops after winter barley or EFA fallow,” he adds.

“Overall we seem to have achieved what we hoped, in terms of establishing the crops and reducing numbers, and it  certainly merits further investigation.”

certainly merits further investigation.”

Helen Wilson, head of forage crops at RAGT Seeds, says FLN is becoming a more important pest in the UK. “Crop damage thought to be caused by poor fertility, compaction and/or poor drainage can often be an FLN problem. Growers are becoming more aware of it and it appears to be more widely spread than many people think.”

While biofumigants may not replace nematicides as long as they’re available, the results show they could keep potato growers in business if such chemistry does disappear, she adds.

“We know biofumigants work well on PCN, though not as effectively as nematicides, and I suspect the same is true of FLN. But they’ll still deliver a good level of control which, in the right rotation, could help to keep numbers down.”

Frontier agronomist Stuart Maltby has been involved with using biofumigants for 15 years and stresses that while the theory is good, there are a number of elements growers must get right in order to get the desired results and not be disappointed.

“It’s not as easy as just putting a cover crop in the ground. You need the same commitment to a biofumigant crop as any commercial crop, even though it’ll end up being incorporated,” he explains.

“The cover crop has to contain the right varieties, established well and must be incorporated at the correct timing – when soil moisture and temperature are above the critical level for the biofumigant gases to volatilise and move through the soil.”

At the flailing and incorporating phase it’s important to have a real understanding of what you’re trying to achieve, believes Stuart Maltby.

“17-20% of the biofumigant effect can be from the roots and the remainder the green top. The cells need to be ruptured to release the gas, so it needs to be chopped as finely as you can,” he advises. “But the most important part of the operation is getting the top incorporated 10-15 minutes after flailing, so ideally you need a single pass machine.

“The surface then needs to be lightly smeared, though not packed, to produce a cap to seal the gas in, stopping it escaping too quickly. It’s also important to understand that you’re only treating the soil to the depth that you’re incorporating into. That means being careful during planting cultivations not to work at a depth below the treated layer, which would mix it with untreated soil,” he cautions.

“Using biofumigants is something we’ll get better at but there’s still a lot to learn about selecting the correct biofumigant crops and getting them to work reliably.”

Suppression only

As far as nematicides go, Nemathorin (fosthiazate) is the only option this season, with Mocap only offering suppression of nematode populations. For early growers in particular that’s a problem because of the lengthy harvest interval for Nemathorin.

Clarifying the definition of harvest interval, Syngenta technical manager, Douglas Dyas explains: “Nemathorin has a harvest interval of 119 days, which means there must be at least 17 weeks from application before burn down or harvesting green crop in order to comply with the label.”

A knock-on effect of an increasing incidence of nematodes in soils is an increased risk of Rhizoctonia infection, warns Yorks-based potato specialist, John Sarup of Spud Agronomy.

He reckons that nematode feeding damage allows the soil-borne rhizoctonia pathogen to get into plants more easily, with infection resulting in stem and stolon pruning which causes protracted emergence.

“If growth is further delayed by wet or cold soils, the effects can be severe. However, rhizoctonia is a relatively weak pathogen that can be effectively controlled in the soil by incorporating Amistar (azoxystrobin),” he says.

“Delayed and patchy emergence has serious implications for crop management. While the canopy appears to recover over the season, it inevitably has a consequence at harvest, with variable tuber size, maturity and quality.”

Damage to root systems, from the combined effects of nematode pests and rhizoctonia attack, is also likely to inhibit the crop’s ability to take up nutrients and water, likely to have a further effect on yield. It also puts plants under greater stress that makes them more susceptible to other threats, such as alternaria (early blight), points out John Sarup.

Groundkeepers may be primary blight source this year

David Cooke reckons blight is likely to develop on groundkeepers after the mild winter and they have the potential to be a source of early infection.

Speaking at the recent AHDB Potatoes’ Winter Forums, late blight specialist Dr David Cooke of the James Hutton Institute, warned potato growers to remain vigilant during this coming season. Despite many potato specialists forecasting a potentially high blight season last year, the peculiar weather patterns last spring and summer meant it turned out to be a low blight season.

“In 2015, a dry April checked primary inoculum of Phytophthora infestans and then a dry June slowed down any established infections. Thereafter, it was generally cool when the relative humidity was high which limited pathogen development,” explained David Cooke.

Despite the unusual season last year, with only 58 positive reported outbreaks compared with 267 in 2014, this winter has been dominated by unseasonal mild and moist conditions. The marked absence of any prolonged frosts means this is no time to forget about blight management, he cautioned.

UK Met Office data backs up the statement, showing how temperatures in Dec were comparable with those that might be expected in Oct, April, or even May. It was the wettest, and warmest Dec on record since 1910 by a wide margin, sitting at 4.1 °C above the 1981-2010 long-term average.

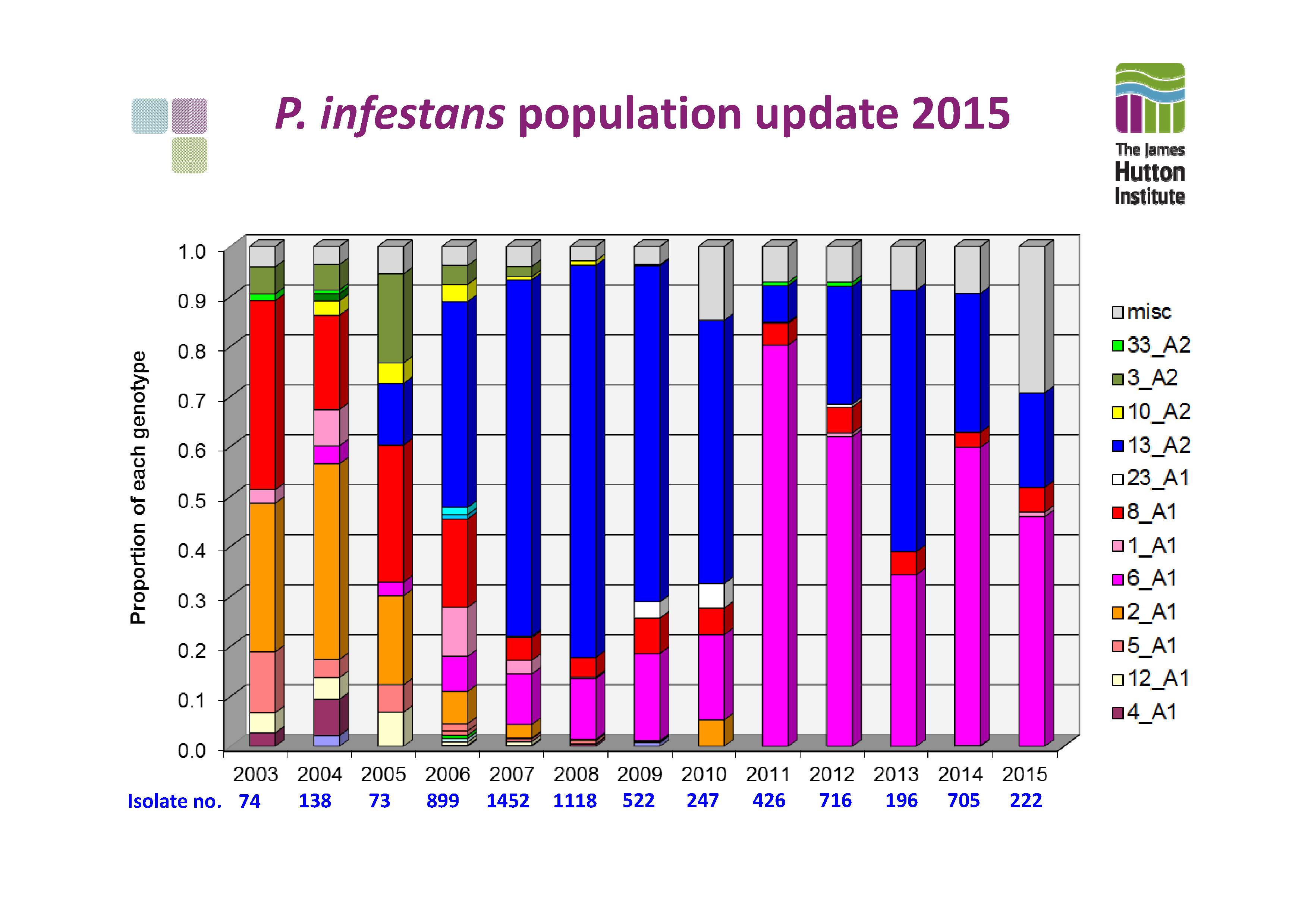

Outlining genotype findings from the past season, David Cooke reported that the strains ‘blue 13_A2’ and ‘pink 6_A1’ continue to dominate the population in England and Wales.

“Both are more aggressive and fitter than previously common strains and they can infect a plant more rapidly, narrowing the control options. Following the wet and warm winter, if this weather trend continues, any weakness in control plans will be exploited by the pathogen and could result in crop losses during the growing season.”

The majority of Phytophthora infestans survives as clones and most inoculum is locally generated. “Target infected outgrade piles and keep a special eye out for groundkeepers. These should be an even more important focus because groundkeepers will have continued to grow over the winter, following the lack of any real frosting. Blight is likely to develop on them and they have the potential to be a source of early infection.”

The picture in Scotland is a little different than the rest of the UK, explained David Cooke, with a much larger proportion of novel types in the blight population. “The blue 13_A2 genotype has almost disappeared and we’re finding a more diverse population in Scotland with a high proportion of novel types especially in North Aberdeenshire, along the Moray coast.

The strains ‘blue 13_A2’ and ‘pink 6_A1’ continue to dominate the population in England and Wales.

This suggests that in Scotland the pathogen was sexually recombining and producing oospores, known for being more challenging to manage.

“While a real concern to the industry, we fortunately found that the novel strains were mainly confined to localised regions of Scotland, and in fact were largely originating from other crop sources. There’s very little evidence of spread of these novel strains via seed or air, either between or within seasons,” he reassured growers.

Thumbs up for Praxim

Praxim (metobromuron) was a welcome introduction to the potato herbicide armoury last season, especially as some of the old stalwarts are under close scrutiny by CRD. After a full seasons experience in 2015, has it lived up to expectations?

As far as agronomist Stuart Maltby’s concerned, the answer is a ‘yes’. “Praxim can be used pre-emergence right up to cracking of the ridges and I’m comfortable using it late on when potatoes are very near emerging. I haven’t seen any adverse crop effects so it appears to live up to the claims of good crop safety on all soil types.”

Stuart Maltby has his own potato demo site near Holbeach where he’s able to run a number of ‘experiments’ both on and off-label, though the latter requires crop destruct. “I looked at Praxim on the demo site last year and investigated a number of different tank mixes and rates,” he explains.

So what were his key findings? “There’s a very definite drop off in performance when used at 2 l/ha rather than 3 l/ha. When used at 2.5 l/ha there’s still a slight drop off in comparison to the 3 l/ha rate. At the full rate of Praxim (4 l/ha) there was no noticeable difference to using 3 l/ha,” he explains.

“The conclusion I’ve come to, is that you need to be using Praxim at 3 l/ha and definitely not below 2.5 l/ha, and then only with a partner product, such as Defy (prosulfocarb) or Sencorex (metribuzin). There’s an impression that Praxim is highly priced and for that reason some growers aren’t using rates that are robust enough. At the 3 l/ha rate, I’m seeing broad-spectrum weed control and good longevity on weeds like bindweed and willow weed (pale persicaria).

“There’ve been issues in a few following wheat crops where clomazone (Gamit 36CS) and metribuzin were applied the previous spring to the potato crop. I’m not seeing any visible effects in wheat this year following potatoes where Praxim was used in 2015,” he notes.

Although there aren’t any buffer zone restrictions for Praxim, Stuart Maltby reminds growers to be mindful of the buffer zone requirements of any partner products.

Agrovista agronomist Luke Hardy advises growers in Shrops and was keen to try Praxim last year, particularly because of the likelihood that linuron may soon disappear and leave a yearning gap for a light land herbicide replacement.

“I have a lot of light land in my area, so there’s potential for problems with crop damage if using metribuzin. I’ve used Praxim at 2 l/ha in tank mix with Defy on light land where fumitory is the main problem. On the heavier land I’ve either used metribuzin as a partner product or a three-way mix of Praxim plus metribuzin plus clomazone,” he explains.

According to Luke Hardy, Praxim looks to be so much more than just a linuron replacement. “It’s expensive compared with linuron but also offers flexibility and a broader spectrum of weed control, with activity on fumitory and wild oats. Praxim controls a weed spectrum very complimentary to the activity of metribuzin which makes them ideal tank mix partners,” he says.

Although Praxim appears expensive in comparison to other pre-ems, he believes it’s money well spent. “Last season, no post-em follow-up treatments with Titus (rimsulfuron) were needed where we used Praxim.”