Centenaries are always opportunities to examine the present by reference to the past. This is particularly so in 2018 when we look back to that momentous year in British history that marked the end of one of its darkest chapters – the First World War.

Centenaries are always opportunities to examine the present by reference to the past. This is particularly so in 2018 when we look back to that momentous year in British history that marked the end of one of its darkest chapters – the First World War.

Away from Flanders bloody fields, in considerable contrast, 1918 was also a golden one in the corn fields of Britain. The harvest of 1918 proved a bumper one with near perfect weather. It was a big harvest across a much expanded acreage with wheat yields in places exceeding that sought after mark of excellence – a ton to an acre.

What’s more the wheat price had doubled since 1914. In the corridors of power, the strategic importance of food had seen a political revival. Writing in his memoirs some time later, the then Prime Minister Lloyd George acknowledged the triumph of the 1918 harvest where Britain’s farmers had seen off the spectre of severe food shortages that had been a real possibility in 1917.

But amidst all this arable euphoria there was a darker side to the way the Golden Harvest of 1918 was reported. The suspicion was farmers were profiteering while the nation suffered the privations of war. There was a cartoon to that effect in the Daily Mail. The umbrage felt by farmers was considerable. The crux of their feeling of injustice was that while the war had indeed seen a reversal in fortunes for British farmers, it was from a very low base in 1914 where prices were so low that not much was being produced leading to the crisis of 1917.

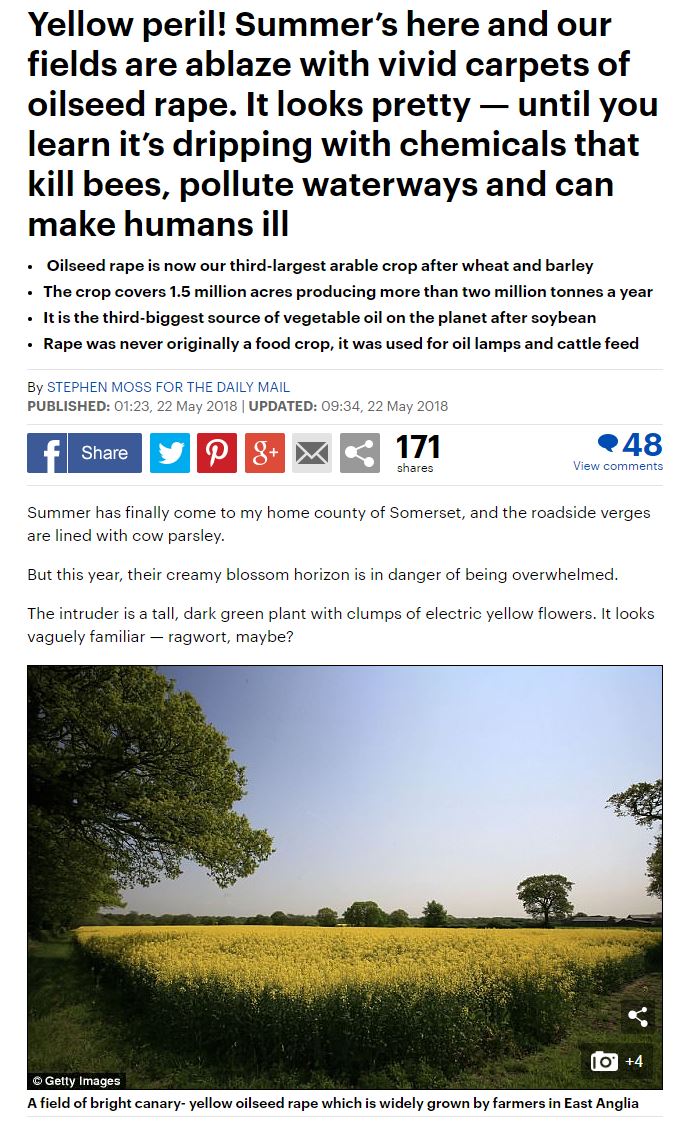

This bit of history came back to me when someone brought to my attention a 2018 article in the Daily Mail entitled ‘Yellow Peril’ where oilseed rape was luridly demonised in a manner borrowed from a 1950s cheap horror movie. Aside from the throw-away nonsense about the crops dripping with insecticides, what caught my eye were claims that OSR acts as some sort of death trap for reed buntings. The accusation was along the lines that farmers lure reed buntings to nest in our crops then wilfully slaughter the brood with combine harvesters.

The Daily Mail marked 100 years of misinforming the public about farming last month with some throw-away nonsense on ‘yellow peril’.

This line of argument seems particularly unfair when it twists through 180° what is in reality a positive conservation story. Most reed buntings fledge in June so they enjoy unharmed the nesting canopy created by farmers. While the less important second broods in July can run the risk of not departing the crop before harvest, what clearly helps here is chemical desiccation with diquat or glyphosate, which as we know is the alternative to swathing in early July.

The double irony here is diquat is in danger of failing re-registration and one of the reasons for this is, wait for it, its exposure to nesting birds. Unfortunately, what regulators do not consider is the exposure of nesting birds to the swather.

So I have duly written to the Daily Mail about the piece. The trouble is by the time I’d worked through all the factual errors, it was too long for the letters page. So as a back-up plan I’ve also written to the author convivially inviting him out to the farm.

So here’s a thought to leave you with as your prepare to spray off your OSR crops –unfair criticism of agriculture in the popular press is officially one hundred years old.

Guy Smith grows 500ha of combinable crops on the north east Essex coast. @EssexPeasant