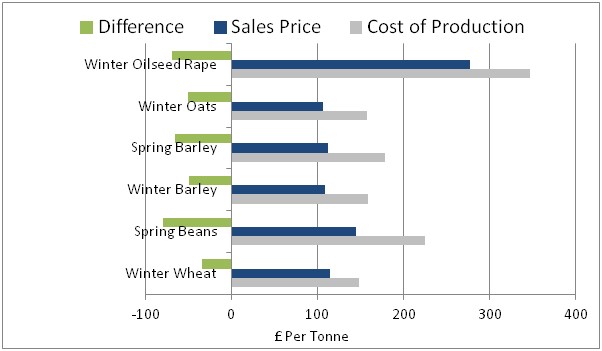

Amidst the ever-increasing confusion surrounding Brexit, life goes on as normal. For the majority of farmers that means producing crops at a higher cost/t than they’re selling for. According to the latest Farm Business Survey figures, it’s a very salient fact that, when all costs are factored in, the average arable farm lost £34 on every tonne of wheat produced, £50/t on winter barley, £69/t on winter oilseed rape and a staggering £89 on every tonne of spring beans sold in 2015/16.

Source: The Farm Business Survey www.ruralbusinessresearch.co.uk

For those who have switched to spring cropping as part of their blackgrass control strategy, a sobering statistic is that spring barley generated the greatest negative margin; the average cost of production was £178/t. And this was on a record-breaking national yield of 6.5t/ha, but when sales prices averaged just £112/t, this made for a significant loss.

Looking at these figures, it’s fair to assume our industry has got itself into an unsustainable situation and the only reason many businesses keep going is because 87% of farm incomes come from subsidies. It remains to be seen if the overwhelming vote by farmers to leave the EU was a master-stroke or financial suicide, but then you could argue that it’s the CAP that allowed us to get in this back-to-the wall situation in the first place.

The UK never did fit the European model when it comes to agriculture. Our average farm size is much larger for starters, so rather than support smaller family units, the CAP allowed British growers to get bigger and splash out on new kit. Big farms became bigger, swallowing up the very smaller farms the CAP sought to protect and stifling new entrants in to the industry.

We were encouraged to produce surpluses because of protection from world prices by intervention buying, creating the grain mountains of the 1980s. And then the ‘MacSharry’ reform of the 1990s, started the shift from product support through prices to producer support through direct income support and land prices soared overnight.

Last year, the average UK cereal farm received a BPS payment of £166/ha after costs. This effectively subsidised every tonne of wheat produced to the tune of £17, and of spring barley to £26/t. So as we contemplate farming without direct production subsidies, which seems the inevitable outcome, it’s becoming more important than ever to focus on the costs of production.

Farms are economising and costs are down, according to the latest figures. Fixed costs on cereal farms averaged £653/ha in 2016, a fall of £29 from the previous year. Labour costs fell by 4% and the machinery bill by 9%. And it’s not just cost cutting that is helping farms deal with low prices and uncertainty. The report highlights that more targeted agronomy is reaping rewards as well, and within this month’s pages there’s much food for thought when it comes to refining agronomic practices.

Increasingly efficiency and sustainability has to be the future aim for farming. I don’t believe the UK policy-makers are going to grant growers any particular favours. A recent report by the Policy Exchange (a leading ‘Think Tank’), entitled Farming Tomorrow makes clear the sort of pressure government will be facing.

It says the following, “The Common Agricultural Policy has, at great expense, reduced agricultural productivity by lessening competition and supporting inefficient farmers, and increased costs for consumers. Outside the EU, the UK will be free to abolish tariffs on food products, which will unlock new trade deals, help developing countries and deliver cheaper food for consumers. We can also reform the agricultural subsidies regime so that we reward farmers who deliver public goods like biodiversity and flood prevention, rather than rewarding wealthy landowners.”

Plainly the authors haven’t read the Farm Business Survey figures which reveal that far from being wealthy, UK farms are struggling. But much of what they recommend in the report makes sense. Equally government officials need to be reminded not to take their eye off-the-ball when it comes to food safety, and that is one of the very positive things that has come out of the CAP.

Our industry is distorted by its dependency on subsidies for income, but we can innovate our way out of this mess.