The government’s proposed withdrawal agreement will allow UK scientists to progress research into new breeding technologies, states Michael Gove.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

Defra Secretary of State Michael Gove has given his clearest indication to date that he wants UK scientists and plant breeders to press ahead with gene-editing, despite a European court ruling that classes crops bred with the new technique as GMOs.

At the CLA’s Rural Business conference in London on Thursday (29 Nov) he pledged that Defra would “follow the science” and ensure UK farmers had access to tools that would “improve productivity in a genuinely sustainable way”.

“I think gene editing allows us to give Mother Nature a helping hand, to accelerate the process of evolution in a way which can significantly increase yield and also reduce our reliance on chemicals and other inputs,” he told delegates.

Michael Gove wants UK scientists and farmers to “lead the way” on gene-edited crops.

“There is a potential there for Britain and our scientists and our farmers to lead the way.”

He recognised that “there are challenges and we have to proceed with caution” but dismissed the position against new breeding technologies (NBTs) taken by groups such as the Soil Association and the Sustainable Food Trust.

“If the science leads us to a particular conclusion, even if there are individual lobby groups that express their legitimate concerns, we will ensure those scientific tools are there,” he pledged.

He was quizzed on this by Yorks farmer Stephen Fell, who pointed out the Court of Justice of the EU ruling, made in July.

This classifies as GMOs crops derived from NBTs such as CRISPR, a technique that performs precise cuts or edits to a plant genome to derive new traits.

Scientists argue the method is similar to and indeed more precise than naturally occurring mutations, or older forms of mutagenesis, such as the method used to breed herbicide tolerance into Clearfield oilseed rape.

“How do you square [your support of agricultural innovation] with your supposed support for the Withdrawal Agreement?” Stephen asked the secretary of state.

“This would tie us in to the EU’s aversion to technology and science-based evidence, clearly demonstrated by the scandalous decision to ban gene editing.”

But Michael Gove said the provisions of the proposed EU withdrawal agreement require Defra “to broadly maintain high environmental standards” which would be achieved through the Environment Bill and an environmental “watchdog” he plans to set up.

CJEU jurisdiction

“There are some people who think that simply because we have committed to maintaining high environmental standards that we will remain subject to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice.

“We won’t,” said Michael Gove.

“What we will be doing is achieving high environmental goals by different means and means that do allow for greater innovation.”

The EU has accepted this new legislative approach, he said, which gives the UK “space to innovate as well”.

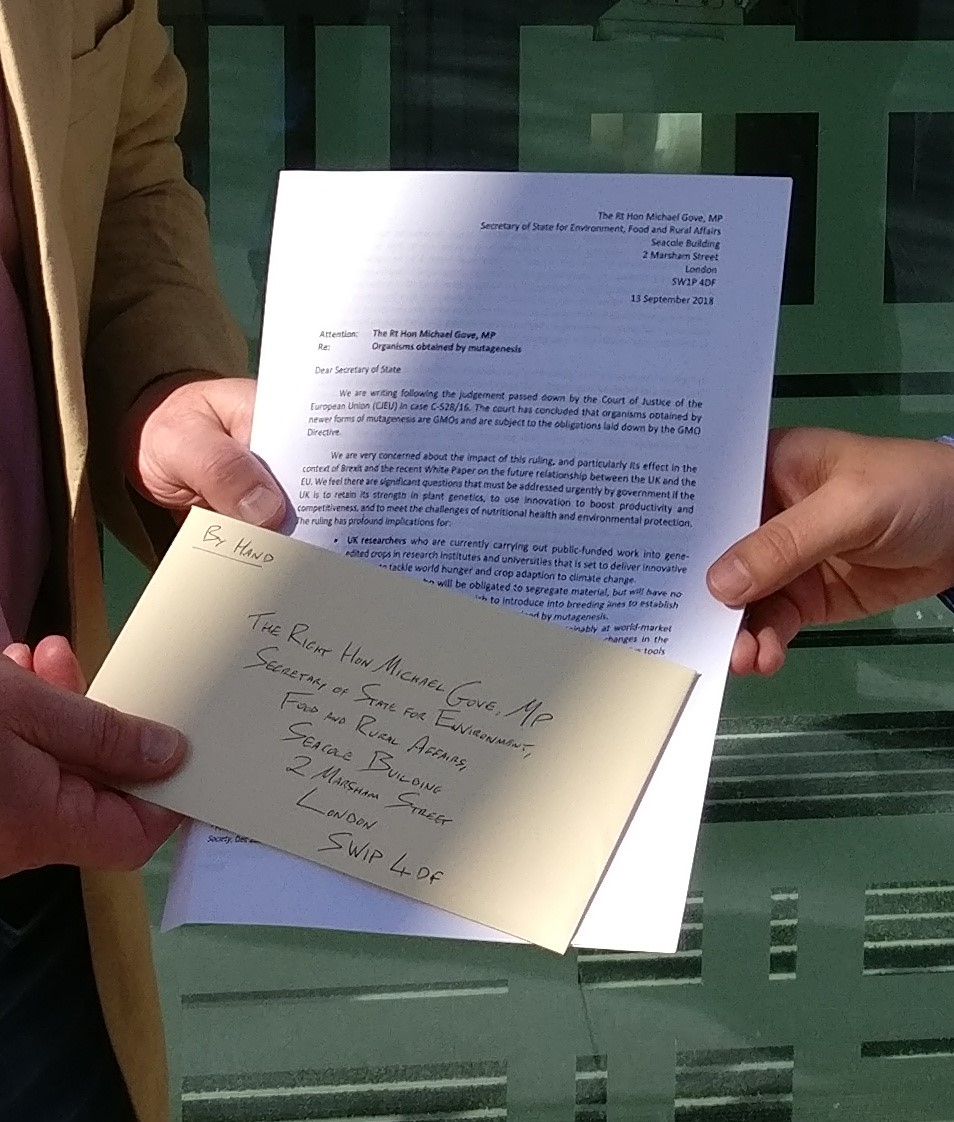

The letter has been signed by 33 UK organisations

This clarification on Defra’s position on gene-edited crops follows a move by farming leaders and the UK agricultural industry who joined scientists in requesting the government urgently addresses how research and future use of gene-edited crops will be undertaken.

A key concern is that gene-edited plant material, developed in the UK in glasshouses and laboratories, much of it using public funding, is now ready for small-plot and field trials.

But scientists cannot justify what they see as the prohibitive cost of obtaining the licence required to release GMOs, then follow the strict protocols to minimise the risk of gene-edited material escaping to the wider environment.

A letter, signed by 33 research institutions, universities, plant breeders, crop agronomy companies and biotech multinationals, as well as industry, farmer and landowner organisations, was delivered to Michael Gove in September.

The letter requests a round-table meeting involving all stakeholders and Defra to agree a clear way forward on research and future use of NBTs.

Farming minister George Eustice responded, saying the government wanted the UK to be “a leading player” in developing applications of NBTs, such as gene-editing.

“Our view remains as we argued to the Court, that GM regulations should not apply to gene-edited organisms where the changes to their DNA could have occurred naturally or through traditional breeding methods,” says the letter, sent in October.

The round-table meeting is due to take place in the New Year.