Zero tolerance on blackgrass is all very well, but what happens when it all goes wrong? CPM assesses tools designed to cut off the weed in a standing crop.

Reducing the seed return is always a good thing, but there is an element of fire-fighting here.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

You do get a gratification, mixed with a despondent sense of desperation, as the Weed Surfer passes over the top of the wheat crop. The crop itself escapes remarkably unscathed, but around 80% of the blackgrass heads, that were about 150-200mm above the wheat, have been removed. A proportion of these are just knuckled over, however, and some are still lurking untouched in the crop canopy. So the question is: has it done any good?

The aim is to reduce the number of viable blackgrass seeds returned to the seedbed. The idea is to cut off the head before the seed has set. The timing is mid June – just as the heads appear above the wheat crop and the window to spray out the patch with glyphosate has probably closed. It’s not going to make a significant contribution to blackgrass management, but the theory is that it may be a better spend of resources than a post-emergence graminicide where resistance levels are greater than 50%, and at least you still have a crop to harvest.

“Reducing the seed return is always a good thing, but there is an element of fire-fighting here,” comments Dr Lynn Tatnell of ADAS. “If you want the practice to be effective, you have to remove the heads before they finish flowering – after that, the seed is viable.”

The difficulty is that flowering for blackgrass takes place over a protracted period, so the ideal time to perform the operation is far from clear-cut, notes colleague Dr Sarah Cook. “Generally the cut-off date to burn off patches with glyphosate is 1 June to avoid any viable seed being present.”

- The Weed Surfer hit about 80% of the blackgrass heads, but some were just knuckled over and some were still lurking untouched in the crop canopy.

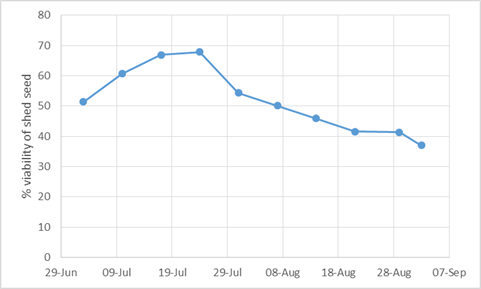

Work carried out by Dr Stephen Moss gives an indication of viability of seed shed over time (see chart on pxx).

But what about numbers? A pass with a Weed Surfer would realistically remove somewhere in excess of 50% of the heads. Multiple passes would improve the clean-up rate and could be timed closer to flowering to reduce the number of viable seeds. So, in the absence of efficacy trials and dependent on approach, you could expect perhaps a 50% reduction of viable seeds.

“If you’re starting with a high population – 800-1000 heads/m² – reducing this by 50% would still leave a population of 50,000 seeds/m², and I’d say that’s starting from the wrong place,” comments Sarah Cook.

“But in a field with less heads, then a 50% reduction is not bad. The blackgrass has already caused you yield loss in the crop, eaten your nitrogen and generally had a good time. Reducing the seed return is a start, but it’s always better that there was no seed return at all – i.e. burning it off before Christmas.”

Fire-fighting tools

Those growers without such foresight, or who voluntarily relegate themselves to the ‘fire-fighting’ zone, can benefit from the experience of the organic sector when it comes to tools to do the job.

The Weed Surfer is supplied by Norfolk-based CTM. Four-blade rotors mounted beneath a steel-framed canopy take drive from the tractor’s 1000rpm pto. There’s a hinged, end-mounted drawbar and removable road wheels for road transport, and it can be fitted to either the front or rear tractor hydraulics in the field.

Two wheels, mounted near each end of the canopy, travel through the crop and maintain height, and there’s a

The viability of seeds in the winter cereal crops

hydraulic option, allowing the operator to trim the angle of the Weed Surfer on the move. There are 2 models – the 8m version has 10 rotors and a 6.4m cutting path, while the 10m model has 14 rotors and cuts an 8.9m strip.

The CombCut is a tool that’s come over from Sweden. Blades mounted on a metal bar are designed to comb through a narrow-stalked cereal crop, leaving it intact, but taking out larger weeds. Hydraulically driven, rotating brushes are designed to drive the crop and weeds through the comb, and the angle of the knives can be set, both laterally and horizontally, depending on the desired aggressiveness of the cut.

It acts as a scythe and its primary use is as a comb to remove broadleaf weeds such as thistle and charlock. But it

James Alexander reckons multiple passes are needed and timing is key to ensure seed isn’t viable.

has been used with some success on blackgrass in a field of organic oats by farmer and contractor James Alexander of Oxon-based Primewest.

“I saw it at Cereals four years ago, and thought of it as a tool for thistles. But then this year we had a real problem with blackgrass, so I asked for a demo.”

It’s available in a 6m or 9m version, folding to 3m for road transport, and while the minimum forward speed is 8-10km/h, it has been used up to 22km/h. “You need the forward speed to give you the scythe action. In thicker patches, you slow down and rely more on the brushes to do the job, but it’s not designed for thick blackgrass – we tried a field and it was hopeless,” says James Alexander.

Multiple passes through a thinner population does appear to be effective, he says. “But timing is key. Each pass probably knocks out about 50% of the heads above the crop. It does leave a lot unscathed, so I wonder whether a reciprocating blade would do a better job.”

Such a machine is not known to be operating in the UK (although CPM would like to know if there is one). While a piece of kit based on a swather may do the job, a trawl of YouTube throws up a number of ingenious European adaptions that could have potential.

One of these is the double-knife mower, developed by Bavarian organic grower Max Bannaski, who farms a smallholding near the Austrian border. “I needed a new system to manage my pasture – a drum mower was too aggressive for my vulnerable heavy soils. But nothing available would fit the bill,” he tells CPM.

So he developed a wide, front-mounted hay rake, and followed this up with a double-knife mower that he sells through his company BB-Umwelttechnik. The mower comprises a reciprocating blade, similar to a combine knife, and is available in widths of 1.65-11m. The larger, 7-11m versions can either be a front-mounted ‘butterfly’ with folding wings, or a front-mounted 3m unit and wings behind – the ‘divided butterfly’.

“I’ve sold around 75 machines, but I’m getting a lot of interest in a mower that will cut above the crop,” says Max Bannaski. So an adapted version, now in use in Sweden, has wheels mounted on the wings to set the height. Initial trials have proved successful, he says.

“I’ve had a lot of interest from England from growers with bad blackgrass. This winter, I’m planning to develop a 12m version specifically to cut above the crop that’ll fold to 3m.”

Time to test for resistance

While cultivators and mechanical tools may now be the best tools to reduce the blackgrass burden, it’s still a good idea to take samples and test for herbicide resistance, says Dr Gordon Anderson-Taylor of Bayer.

“It’s true that resistance to herbicides is now commonplace in blackgrass, so if control from post-ems didn’t meet expectations, think about collecting seed for a test this July.”

The results tell you if there is resistance against ALS inhibitors such as Atlantis (mesosulfuron+ iodosulfuron). If there’s a high level of resistance then control will need to be frontloaded with appropriate cultivation, use of glyphosate and pre-em herbicides including Liberator (diflufenican+ flufenacet) that has been little affected by resistance so far, he says

“In July, you’re testing survivors of the herbicide programme so it’s no surprise when the results report resistance. What you have to factor in is the plants you did manage to kill, and what proportion of the population the survivors represented.

“The following year, you wouldn’t expect to see an entirely resistant population. Firstly, because there are still susceptible seeds in the seedbank and secondly, some offspring of resistant plants may also be susceptible,” says Gordon Anderson-Taylor.

The best time to take samples is mid to end of July when 10-20% of the seed has shed, advises Lynn Tatnell. “The biggest error made when sampling is to take unripe heads.”

An accurate assessment of dormancy won’t be available this year as funding for the service, that ran for 15 years, has now ceased. A limited number of samples will be tested later this year, while ADAS’ predictor model currently suggests a high dormancy, based on one set of weather data.

How to sample blackgrass

- Collect a small mug of seed. Avoid collecting intact heads as they’re unlikely to be ripe

- Collect a representative sample. Travel across 2-3 tramlines and a length of about 100m

- Sample patches of blackgrass and mix together

- When dry, transfer seed to a paper envelope (not plastic) and send for analysis.