Now’s the time to take your crop in hand and set it up to ensure it makes the most of whatever the season brings. CPM finds out how early nutrient programmes can be refined to optimise growth.

Nearly everything you can do to build biomass and give the crop the momentum it needs to deliver you a bumper yield is directly under your control.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

With Brexit less than two months away, it may not feel at present as if you’ll be taking back much control of your arable business – uncertainty over trade agreements, labour and agriculture policy add to the more traditional vagaries of the weather and market fluctuations.

Mark Tucker of Yara, however, prefers to highlight the areas of your business that are under your control, and argues the cards are actually stacked in many growers’ favour. “We’ve had a kind autumn, and many crops, even those drilled late where blackgrass is a problem, are looking fantastic,” he reports.

In terms of starting the spring on the right footing, to build biomass into the crop, Mark Tucker reckons growers are in a good place.

“In terms of starting the spring on the right footing, we’re in a good place. What’s more, nearly everything you can do to build biomass and give the crop the momentum it needs to deliver you a bumper yield is directly under your control.”

Mark’s comments are built on Yara’s long association with the Yield Enhancement Network (YEN). “YEN has really reminded us of the importance of getting the fundamentals right,” he says.

The theory is that the only natural limitations are sunlight and rainfall. Everything else that determines your crop yield comes down to how you look after it. YEN results suggest growers achieve on average just over half their site yield potential, so Mark advocates a commitment to careful measuring and monitoring throughout the season, and to make sure the crop wants for nothing.

“Ultimately, we’re aiming for maximum grains/m², and that’s related directly to number of shoots/m² you set up and then grains/ear. Early in the season, though, building the foundations for later biomass growth is the number one objective – YEN results have consistently shown this – and that work starts now.”

Nitrogen applications drive biomass, he points out. “Take a look at your crop – those drilled later may be shy of a few tillers, and an early application will help increase a wheat plant’s sink capacity, which determines its ability to yield.”

Field conditions could be favourable for such applications this year, he adds, although he has concerns: “Many soils are dry at depth, and there’s a worry we could see a repeat of the 1975/76 growing season, when poorly rooted crops suffered catastrophically.

“Again, early N is the key – for every shoot a wheat plant puts out, it’ll add extra roots, and that gives it the momentum and resilience to cope with dry conditions later in the year.”

One critical factor outside your control is how much phosphate your soil supplies to the crop, he cautions. “When the soil’s cold and wet, plant roots can’t take up the phosphate they need. It’s only once things warm up in April and May that soil P is released. But 70% of a crop’s overall requirement should be taken up in the eight-week period from the end of Feb – if it can’t access that, this’ll limit its potential to build biomass.”

The difficulty here is knowing whether that P is available. “Trials we’ve carried out show up to 40% of applied P can be locked up by the soil in the first 10 days after it’s spread, especially in soils high in iron, aluminium or calcium. So even fertiliser applied before Christmas may not be available to the crop. Soil indices can also be misleading – they indicate extractable P in the lab, which may not equate with what’s immediately available to the crop in spring,” Mark notes.

His comments chime with conclusions from around 10 years of AHDB-funded work into phosphate, carried out by ADAS, Bangor University, NIAB, Soyl, Frontier and others. Professor Roger Sylvester-Bradley of ADAS has been pulling the results together: “Take control is very much in line with what we’re concluding from the research,” he says.

“We’re concluding that P management needs to embrace much more of a crop focus.” He suggests three key target areas for growers:

- Crops: Work out whether, and where on your farm, crops are P deficient. There are several ways of doing this – some are new, like using grain P analysis

- Soils: Judge the size of your soil P reserves across the farm. Decide how big you want them to be – so whether you will aim to keep them at Index 1, 2 or 3 – and importantly, work out how they are changing

- Fertilisers: Use the most efficient form of fresh phosphate to avoid deficiencies, especially for crops growing in low P zones, and use it annually.

There will be changes to AHDB’s Nutrient Management Guide RB209, he confirms. “Current guidance is very soil-focussed, and also rather general. For instance, it says that soil P changes by 1 mg/l if net phosphate removal or addition in an arable rotation is “around 40kg/ha of P2O5”. Our research suggests 20-30kg/ha is a more accurate figure, but also shows that this can be hugely variable between farms.”

Roger explains that some farms can build the soil P bank by 1 mg/l with as little extra net phosphate as just 7kg/ha, but others need up to ten times as much. “Growers who have mapped their soil P can use that data to work out how it behaves year on year. But before you get to know your soil, it’s important to get to know your crop.”

To calculate offtake, RB209 assumes grain P levels of around 8kg/t. “We’ve completed a review, including YEN data, which suggests this is actually closer to 6kg/t, and again, we suspect that this varies from farm to farm. Our experiments have shown that anything below 6kg/t (or 0.32% of dry grain) suggests a deficiency,” he notes.

Monitoring grain P as well as soil analysis will bring you a much more precise understanding of how the phosphate is behaving in your soils. “You can also use leaf analysis to find out how levels vary within a season,” he adds.

Roger suggests this as a more refined strategy towards phosphate than the broad-brush traditional method of aiming to keep soils at Index 2 – indeed the years of trials show that crops can often perform just as well at Index 1, although for some rotations, such as those that include maize, vegetables or roots, maintaining levels at Index 3 works best.

And it’s not just about maximising crop performance – phosphate run-off is an increasing environmental concern, he notes. “Regulation looms over the use of phosphate, and growers could find applications capped. Unless we can work out how to use fertilisers more efficiently, this could limit yields and take even more decisions out of their hands.”

He points towards the proposed ‘What Works for Farming’ idea potentially providing a really enlightened approach for making P management both more profitable and sustainable. This is an industry-led plan to build an on-farm evidence base for better productivity and sustainability – one with growers firmly in control.

“We are already using farmers’ trials in our research, and these have been excellent at showing what really works in practice – and also what doesn’t. So, like the YEN, we could form a Phosphorous Efficiency Network (PEN), administered by What Works. This could improve and promote on-farm P monitoring, test products and practices for P-use efficiency, while developing best practice and relevant science to be shared among growers to help get better value from their P applications.”

But what about making adjustments this season? “There are lots of different fertiliser products and different ways of making fresh P applications, and they don’t all work the same way,” notes Roger.

The most common form is orthophosphate, explains Mark. “Monoammonium phosphate (MAP), diammonium phosphate (DAP) and triple super phosphate (TSP) are high in orthophosphate. This is a readily available form for the plant, but it can be locked up quickly by the soil.”

Dicalcium phosphate needs to be applied to the soil and broken open by root exudates before it can be utilised by the wheat plant. Polyphosphate must also be broken down in the soil, but requires just soil moisture to do so. “Ideally you want a mix of these forms in the soil bank to give you a controlled release of P through the season.”

Mark’s advice to those growers who have already applied some autumn P, or have their season’s N fertiliser requirements in the shed, is to consider a foliar treatment.

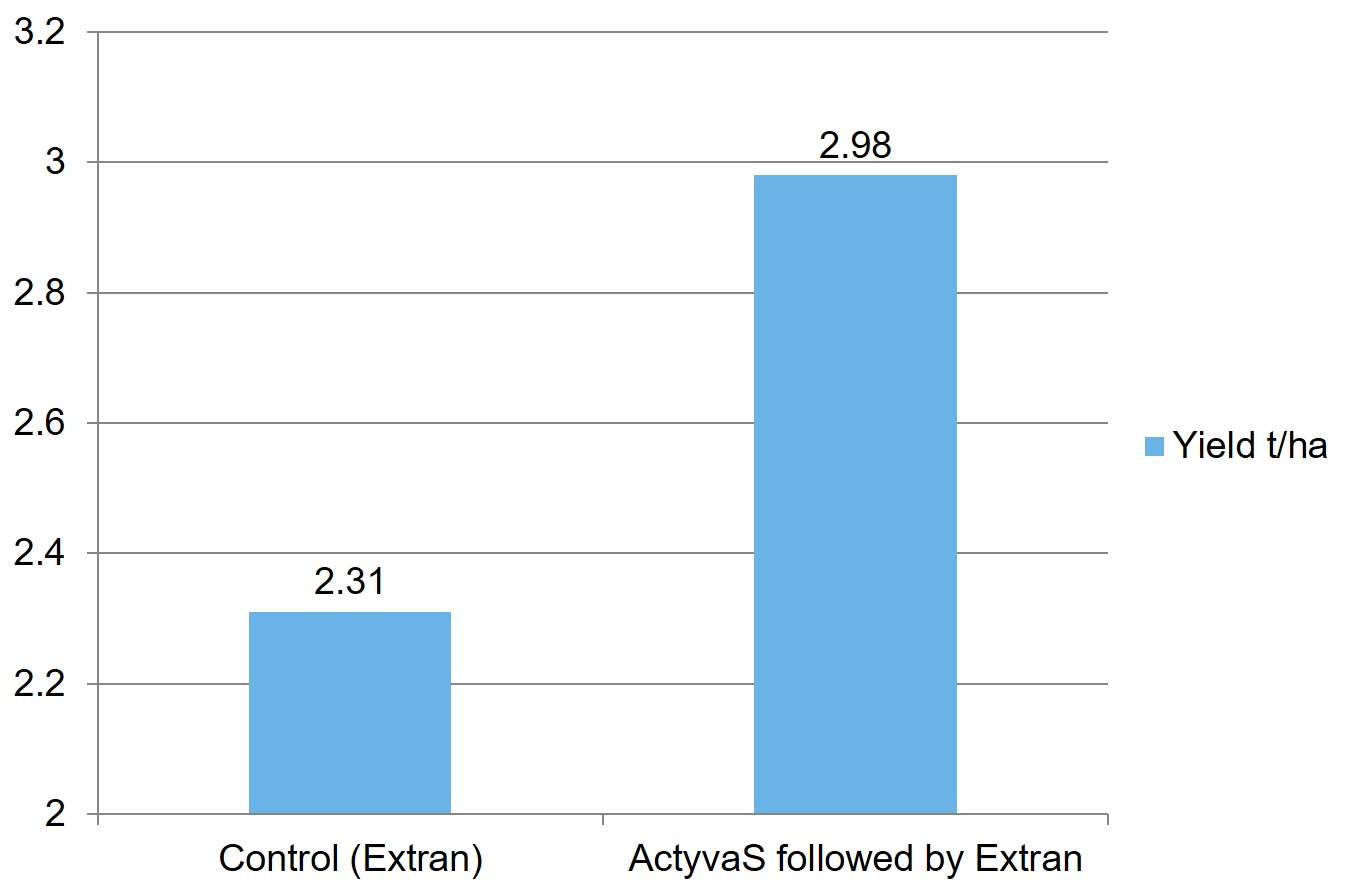

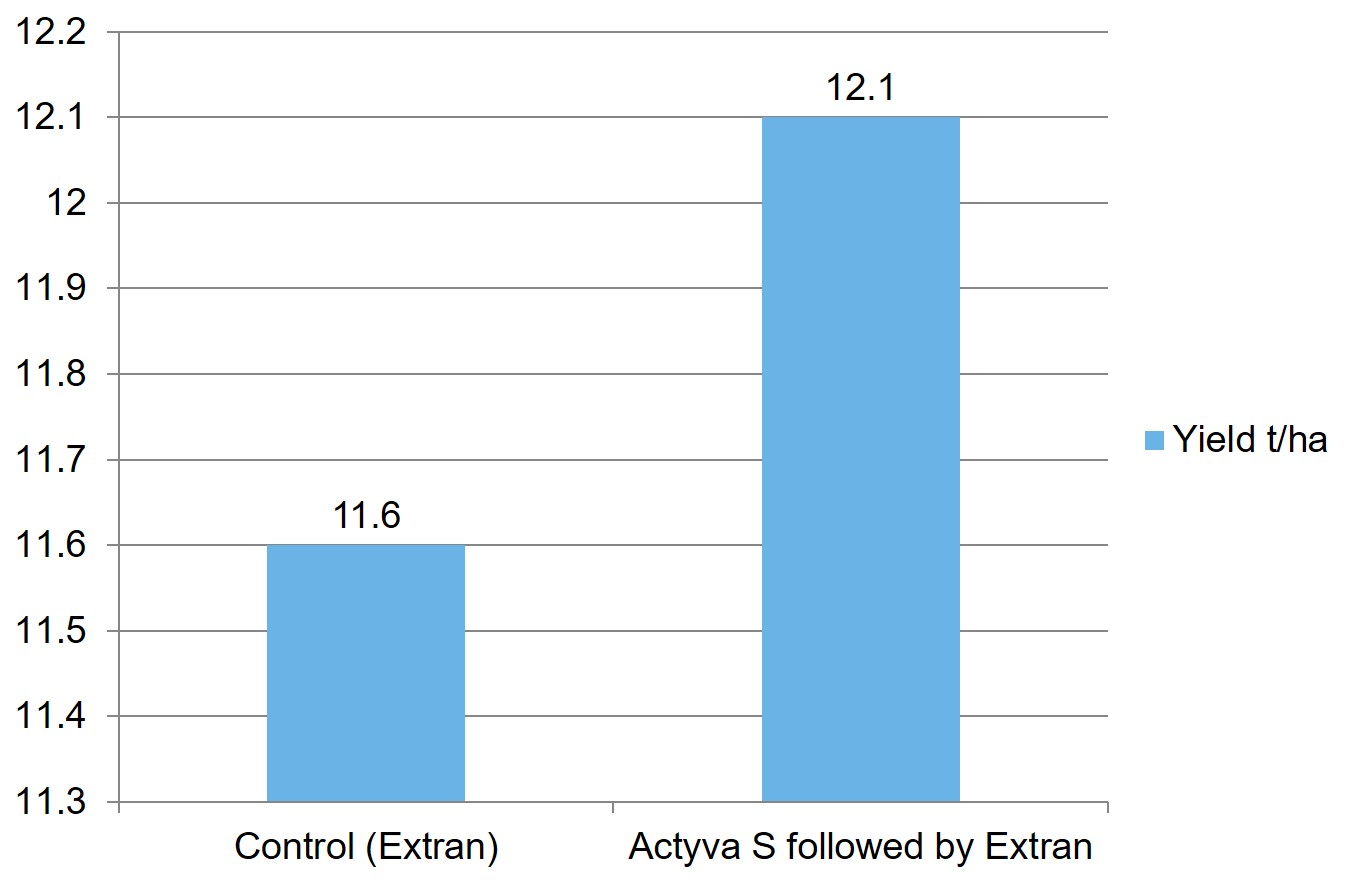

“Yara trials suggest good responses to spring applications of either solid or foliar P (see chart on pxx), but an application to the leaf, typically at the T0 fungicide timing, is a very efficient route.” He recommends Magphos K, which at 5 l/ha puts 2.2kg/ha of P2O5 on the crop as magnesium phosphate and also tops up potash levels.

Those applying a solid form in the spring will typically look to put on around 35kg/ha of P2O5. “Solid forms can be as little as 10% efficient, but you don’t lose the fertiliser – it stays there in the soil and will be released over time.”

If you haven’t yet bought all your N fertiliser, Mark recommends a compound NPKS application as soon as you can travel in the spring. “ActyvaS will supply around 40kgN/ha to help kickstart spring growth. If the crop needs extra N, YaraMila 52 S (20.6:8.2:11.6 + 6.5%SO3) is a better option.

“Both products contain all three forms of phosphate in the right balance, and as they are uniform sized and compound, you get an even spread with all the nutrients in every prill.”

Mark believes it’s these early spring applications that can make all the difference to how a crop puts on its biomass and sets it up for the season. “Our trials overwhelmingly show the benefits of spring-applied P in particular, and it puts you back in control of the nutrients available to the crop. That way, if the rain and sunshine come right later in the season, you’ll have a crop with momentum that’ll yield closer to its site potential.”

Yield response to spring-applied P&K in winter wheat and oilseed rape

Source: Yara UK trials data, 2015 (wheat, left) and 2016 (OSR, right); Extran 33.5% N; ActyvaS 16% N, 15% P2O5, 15% K2O, 6.5% SO3.

Right time to boron?

You may have thought we’ve learned everything there is to know about boron, but recent Yara trials suggest there may be an advantage in an early application.

“We routinely trial a range of micronutrient applications over a number of sites to refine understanding of rates and timings,” explains Mark.

“On one site, we trialled boron at an early timing, just to confirm that the later timing, to coincide with grain set, does bring the best result. To our surprise, the early timing also brings a yield advantage. The site was on the borderline between sufficiency and deficiency as well.”

He cautions this is just one year of trials, and further work will take place this spring to delve a little deeper, but there’s logic behind the results. “Boron is an essential nutrient for cell division, and plenty of that is taking place in the plant from the moment it wakes up in the spring, but it may struggle to pull on the nutrients required. An early foliar treatment gives it easy access.” YaraVita Bortrac, for example, contains 150g/l of boron, and just 0.5-1 l/ha with the T0 spray may be all that’s needed, he suggests.

“Boron is a somewhat forgotten nutrient in wheat crops – results from our lab analyses of leaf samples sent in by growers for testing show 80% are deficient. It’s needed primarily for pollen fertility, but we’re learning it may also have a role in giving the plant momentum through the season.”

Take control

On March 29, 2019, Britain exits the EU. The move will create unprecedented uncertainty and change for farmers. While much of the change is beyond the control of the average arable business, it highlights the importance of those elements that can be managed.

Few aspects of crop production are more critical than a plant’s nutrition, which is why CPM has teamed up with Yara in a series of articles that brings in some of the latest understanding to build on established knowledge. The aim is to take control of how a plant draws in and assimilates nutrients to optimise every aspect of crop and field performance.

With decades of evidence-based knowledge, Yara continues to be at the forefront of crop macro and micronutrient advice. Investment in technology has resulted in world-leading products that support in-field decision making and precision nitrogen application.