Attentive agronomy and plenty of manure helped one N Yorks grower achieve the highest UK yield with his spring beans, at around 70% above the UK average. CPM visits and discovers the potential may be even greater.

What we want are strong plants that flower to the floor and pod to the floor.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

You’d have thought Richard Wainwright would be savouring his achievement, as he stands for photos with his crystal decanter and bottle of single malt, while cupping a handful of spring beans. The prize trophy was awarded for the highest verified bean yield from the 2016 harvest – his silty loams over limestone near Stonegrave in N Yorks brought in a healthy 6.81t/ha crop of Fanfare.

“It’s actually our lowest yield of the past three years,” he remarks. “I’d expect to get at least 7.5t/ha, and there have been times when the yield hasn’t been too far away from the magical 10t/ha.”

Richard Wainwright probably holds the current unofficial world record for the highest spring bean yield, but reckons the crop’s potential is much higher.

Richard Wainwright took up the challenge, laid down by PGRO around 18 months ago, to steer his crop towards a double-digit yield (see chart below). He farms a total of 600ha at Birch Farm in a family partnership with brother in law Peter Armitage and father in law Ian. Whether the clay over gravel or silt over limestone soils on the edge of the N Yorks Moors are capable of such an achievement remains to be seen. But he reckons the crop has plenty of potential that for the most part remains untapped.

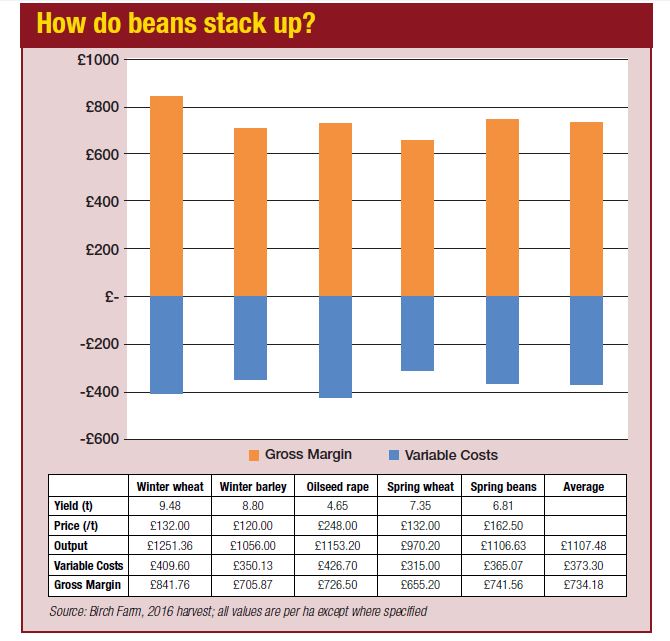

“A lot of people grow spring beans as a rescue crop – it’s regarded as a poor man’s break crop that you don’t have to spend money on, so it gets no love and attention to detail. But year-on-year, beans perform better for us than oilseed rape, and just look at how much time and resource is lavished by most growers on that crop,” he points out.

Besides a keen determination to give the crop everything it needs, he has a second secret that secures a fertile tilth and a crop that’s fit to flourish – muck. The farm has 1400 head of cattle – predominantly continental finishers – while 1000 store lambs are brought in each year to graze overwintered stubble turnips that rotate around the 485ha of arable and precede the beans. The soils receive rich rewards from what these beasts leave behind, reckons Richard Wainwright.

“A trailer load of muck adds far more to the soil than just its nutrient value – it’s a magical soil conditioner,” he enthuses. Up to 50t/ha can be applied, ensuring compliance with regulatory guidelines, and steered towards achieving optimum output from a seven-year rotation in which two winter wheats are followed by either winter barley and OSR or spring beans.

And the suggestion that a spring crop doesn’t work on clay soils is smartly dismissed. “That’s a load of rubbish. In gross margin terms, spring beans perform the same or better than winter crops and help spread the workload.”

Generally a Sumo five-leg subsoiler is the first piece of kit to follow the combine after the wheat’s taken off. “What we do then depends on how much moisture there is – we aim to make a pass with the Sumo 3m trailed Trio, with an extra front-mounted disc unit. But if it’s really dry, we can drill the stubble turnips straight in. We’ll often top dress this with 12t/ha of muck to give it a good start and help keep the moisture in,” explains Richard Wainwright.

The crop’s drilled with a 4m Horsch Pronto, that does little more than scatter the seed on top. “But just like the bean crop, there’s no excuse for skimping on stubble turnips. Both are clear-up crops for weeds, so we use pre-emergence glyphosate and in-crop graminicides to ensure we don’t miss the opportunity.” The total cost of the over-wintered crop is £120/ha, including machinery, he adds.

The store lambs are brought in from early Nov and usually leave the land in Feb. “Then the soil just has to dry. We’re looking to get away from ploughing and you can direct drill the crop. But we like to press the reset button twice in the rotation with the plough – before winter barley and in front of the beans in spring.”

The 6f Kuhn Vari-Master is followed with a pass of a 5.5m Simba Cultipress, and this is carefully timed. “You want to leave the soil to nap and work it when the surface is dry – sometimes what you don’t do is more important than what you do.”

The bean crop’s drilled with a 4m Sumo DTS, aiming for around mid-to-late March into a seedbed that’s relatively rough and “corrugated” to prevent the soil from capping.

“We’re aiming for 35-40 plants/m², so drill at about 40-45 seeds/m². That’s way below the rate currently recommended by PGRO, but there are important reasons to drill at this rate,” he explains.

Firstly, the DTS establishes at 30cm rows, and Richard Wainwright reckons a higher seed rate would result in crowding down the rows. The second, and arguably more important reason, comes down to pollination.

“Beans rely heavily on pollinators to improve pod set, so you have to focus your mind on doing everything you can to encourage them into the crop. What we want are strong plants that flower to the floor and pod to the floor. That means an open canopy that brings in the light and the pollinators – not just bees, but insects too – so that every flower makes a pod.”

The variety is currently Fanfare, and it’ll be grown for the second year in 2017. “We’ve previously grown Fuego, but felt the need to change. Fanfare’s had 2-3 years on the PGRO list and has shown it’s a consistent yielder that doesn’t fall flat, which is important with the amount of muck we apply across the rotation.”

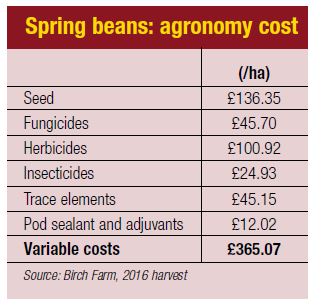

Following a pre-em herbicide of Nirvana (pendimethalin+ imazamox), crop protection starts in May with an insecticide often applied for pea and bean weevil and a graminicide to keep grassweeds in check. Chocolate spot and downy mildew are the main disease threats with an azole plus chlorothalonil sprayed in June and July.

But the July application is tank-mixed with Amistar (azoxystrobin), which does more than just protect the crop, he reckons. “With our open canopy, I’d hope the crop is less susceptible to disease. What we’re trying to create is a sunlight factory and transfer all of that energy into the pods. The Amistar brings more value in terms of greening,” explains Richard Wainwright.

That’s also the philosophy behind a micronutrient programme that sees a total of £45/ha invested. This starts with Nutriphite peak, a phosphite supplement, made with every application from two-leaf stage up to first pods. There’s plenty of manganese also applied – the soils are prone to deficiency – and molybdenum and boron are tank-mixed in as the first flower buds become visible. The crop’s then given a potassium and sulphur boost when it starts to pod up. “That’s when beans are particularly hungry for nutrients,” he points out.

“We want to give the beans a tonic at every pass. A healthy crop mends itself, so the nutrient programme is arguably more important than the fungicides. The crucial point is that the crop must be healthy at pollination so that it doesn’t abort pods.”

He’s slightly more relaxed about bruchid beetle, however. “Up here, we’re the last people to get it. So we just pay attention to BruchidCast, which gives us plenty of advanced warning. We’ve always managed to achieve the human consumption premium, not that it brings in much extra at the moment.”

Harvest is the point that’s critical to making that grade, he believes. “Once you spray the diquat, that sets the clock ticking, and you want the crop in the shed within three weeks. We apply a pod sealant, too, because the pods can be very brittle, especially if you have a hot Sept.”

He aims for a moisture content of 18% or less off the field and circulates ambient air through the crop once it’s in the barn to bring it under 17%. “Then we’ll pass it through the continuous-flow dryer up to four times in batch mode, with just warm air – if it’s too hot the seed will split and stain.

“Then the crop goes back on the floor with pedestal fans. To bring it down to 15%, it may need to go through the dryer again, and that last 1% can be hard to achieve. Keep the crop in the dark, though, as light during storage will also discolour it.”

The award-winning crop itself has already left the farm. “I generally sell the crop in four thirds – I take a conservative estimate on yield when selling forward, so there’s a bonus surplus sold on the open market after harvest. As long as the sample is pale with no bruchid damage, traders get excited as it’s a desirable product and you can get a premium. I don’t have a fixed outlet and look for the best deals on the day.”

What’s left behind is pretty impressive, however – a cursory inspection of the soil that bore the winning crop, now in wheat, reveals a friable crumby structure, and a crop well set up for the season ahead. “If conditions go well, it’s mint – it’ll give you a fantastic entry for wheat. But if the weather turns against you it can be a disaster. Beans can turn your last week of harvest into a two-month struggle,” notes Richard Wainwright.

“If you’re lucky, you get soil in such good condition you could cultivate it with a thorn bush. But if it’s a late harvest, it can be touch and go – we’ve harvested beans and drilled the wheat on the same day.

“But I think the benefit to the following crop is sometimes overplayed. You do get residual N, but sometimes this doesn’t mineralise, so don’t rely on it – it depends on what the weather does.”

And that’s also the pivotal factor for prospects in 2017 and beyond, he says. “Various weather events mean the land still needs to dry out before we can drill this spring, but forward prices are good so there’s plenty of potential for good gross margins. There are EFA rule changes coming in for 2018, and these are annoying as they amount to meddling by the EU. But they don’t change the fact that beans are an excellent break crop.

“Whether we can achieve the 10t/ha crop – again, much depends on the weather and we’ll need all the ducks lined up. All we can do is set the crop canopy up to make the most of the sunlight, and then if we get the right weather at flowering and through pod set, who knows? Maybe we might just do it.”

What is the world record yield for field beans?

The truth is, no one knows, according to Roger Vickers of PGRO. “We’re not aware that a world record has actually been set for field beans, or fava/faba beans as they’re known globally.”

One leguminous crop that has broken the 10t/ha barrier is soybean. According to Corn and Soybean Digest, a new world record of 11.5t/ha was set last year by Randy Dowdy, a grower in Georgia, USA. Poultry litter and a cover crop preceded the Roundup Ready soybean crop, while understanding its nutrient needs and insect pressure were the keys that unlocked the high yield, says Randy Dowdy.

As for field beans, the UK average bean yield is around 4t/ha, although official national statistics are not available for the crop. “We think the UK grower would achieve the highest yields in the world, but we set the target for the PGRO Bean Yield Challenge based on what we believe the genetic potential to be. Our own plot trials along with anecdotal evidence from growers suggest we’re not far off a double-digit figure,” continues Roger Vickers.

The first grower who manages to attain the “challenging but achievable” officially verified yield of 10t/ha before 2020 will win PGRO’s Bean Yield Challenge. The prize is a four-night trip to France for four people, including an overnight stay in Paris, while each year there’s a prize trophy awarded for the highest yield entered.

To qualify, growers must register their crop with PGRO by 1 July in the relevant harvest year. Harvest must then be independently witnessed and verified – the full rules of entry are available on the PGRO website.

“So far as we know, 6.81t/ha is as close as we have to a world record bean yield, although we haven’t gone as far as to get this officially recognised. However, we’re convinced there are growers out there who know they can beat this, and we’d dearly like them to enter their crop so we can learn how to push the potential returns,” notes Roger Vickers.

Spring beans: agronomy cost