In the same year Kent grower Richard Budd achieved a barn-busting 7.2t/ha yield from oilseed rape, on-farm trials with Revystar XE suggest some careful tweaks may unlock similar potential in his wheat crop. CPM visits to find out.

The opportunity to use the new chemistry early and have the results assessed using ADAS’s Agronomics has given us a thorough insight into how it’s best used.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

Considering his heavy Weald clay has received 60mm of rain in the past week alone, Richard Budd’s current crop of oilseed rape is looking remarkably spritely on ground that feels firm underfoot.

“We’ve only managed to get about 40% of our winter wheat drilled this year, but all 150ha of the OSR crop is up and away,” he reports. “It looks good, considering it’s received two thirds its annual rainfall in the last six weeks, but I don’t think we’ll get a repeat of last year’s crop.”

That would be quite an achievement, because Richard’s 2019 crop of Campus yielded an eye-watering 7.19t/ha. It was by far the highest yielding crop entered in the Oilseed YEN (Yield Enhancement Network) and would probably have beaten the world record set in 2018 by Lincs grower Tim Lamyman (7.01t/ha) had it been officially entered and recorded.

The current crop of oilseed rape looks remarkably spritely, but is unlikely to yield the barn-busting 7.2t/ha achieved last year.

But this bounty represents just one of the fascinating features of Stevens Farm, near Hawkhurst, Kent, that Richard farms with his father, David. Alongside 900ha of arable crops (winter wheat, OSR, barley, oats and beans with spring barley, beans and oats), there’s 125ha of top fruit and 75ha of permanent pasture let out on short-term agreements.

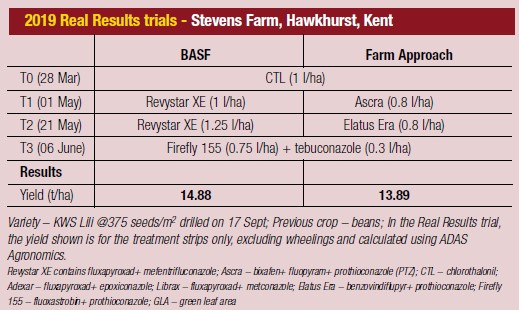

Within the 2019 wheat area was a field also entered into YEN, and within that field was a Real Results replicated tramline trial of BASF’s new fungicide Revystar XE (see panel on pxx). While his farm standard fungicide programme yielded a fairly robust 13.89t/ha, the Revystar plots brought in 14.88t/ha – a yield that would also put his wheat among the top YEN performers of the year.

“For me, farming’s about optimising the inputs to get the best output – that’s why we use YEN,” Richard explains. “The report gives you a good, detailed analysis of how your crop has performed which we use to test and improve how we grow our crops.

“It’s not all about growing the highest-yielding crop, though – we’re aiming for a yield that’s achievable and sustainable. So we’re not going to travel 20 miles to put on a micronutrient simply because YEN’s grain analysis suggests it might be lacking. But it does help us make year-on-year refinements and monitor the incremental benefits these bring.”

So where did that barn-busting OSR yield come from? “We weren’t expecting it, to be honest. Firstly, it’s a good field on Grade 2 Ragstone series, free-draining heavy silty clay. It’s previously been let to a dairy farmer in a maize, stubble turnips and grass rotation, and this was the field’s first year in OSR.

“Secondly, the sunlight levels just went bonkers over the season. I noticed this especially in June which would have been when the crop filled the pods. What we managed to achieve was to set the crop up right so it made the most of it.”

That starts with the crop’s establishment. For around seven years, Richard’s run a controlled traffic farming (CTF) system that puts a 6.5m Väderstad Carrier with cross-cutter discs through just the top 5-10mm to encourage a chit of grassweeds. After spraying off the green cover, this is followed by a 6m Sumo DTS with Dutch coulters that puts the seed in 33cm bands.

“We leave the crop residues – soil organic matter and structure have been steadily improving, along with the yields, since we switched to this strip-tillage system. The DTS puts the seed in a narrow channel tilled in front of the coulters. For our heavy soils that drainage channel is key – it mineralises the nitrogen, you get a good root structure and it allows the crop to get away in the spring. With the OSR, we then follow up about a week later with some DAP.”

Quite controversially, he sows the OSR late with a high seed rate. “Up until 5-6 years ago, we were sowing hybrids in mid-Aug, aiming for 20 plants/m², but found it a bit of a lottery and often had to re-drill much of the area at the start of Sept. So we switched strategy – in autumn 2018, the crop was drilled with conventional Campus at 90 seeds/m² in mid-Sept, looking for 60 plants/m².

“We didn’t get the large tree-like plants some growers aim for, but did achieve a nice, even canopy that was knee-high by Christmas. It all went into flower at an even timing in spring, coming out of flower about 3.5-4 weeks later. With a crop dominated by a main raceme, it had a fine structure during its long pod-filling period, so clearly made best use of the high solar radiation,” reasons Richard.

Although he hasn’t been aiming for the Oilseed YEN top slot, Richard’s crops have moved steadily up the rankings towards last year’s big success. Could this year’s result with Revystar point the way towards top-yielding wheat crops?

“The answers to higher yields don’t come out of a can these days,” he says. “We’re aiming for a healthy start for our wheat crops so we’re not firefighting through the rest of the season. I believe that’s also the best way to look after the chemistry.”

That starts with the soil, continues Richard. “We’re not going to be able to grow big crops on unhealthy soils, and our CTF system is really delivering the benefits here. Our involvement with YEN and with Real Results is helping us develop a truly sustainable farming system and identify points where we can give the crop a helping hand – it’s those small changes that add up.”

Revystar XE trials provide 1t/ha extra yield and valuable insight

This is the third year Richard has been one of 50 growers taking part in BASF’s Real Results on-farm trials. Across a section of a wheat crop, this has compared the farm standard fungicide approach at the main two timings with the BASF recommended programme, usually based on Adexar and Librax.

“It’s been quite exciting to be involved this year, because we’ve used Revystar in place of the usual Ad/Lib programme,” notes Richard. “The opportunity to use the new chemistry early and to have the results assessed using ADAS’s Agronomics approach has given us a thorough insight into how it’s best used.”

The BASF treatment was applied across three tramlines in the eastern part of the field – the area with the most consistent soil type – interspersed with three tramlines that received the on-farm standard. NDVI (normalised

difference vegetation index) maps were taken through the season and these were assessed by ADAS scientists, along with disease levels from samples taken in July. The Agronomics approach was then used to compare the results, using spatial modelling and statistics to allow yield-map data from the combine to be assessed with scientific rigour.

“Last year we had a dry, mild winter and came into the spring with a good, well tillered crop,” reports Richard. “There was a lot of septoria on the lower leaves, but this didn’t develop and by May it was quite dry, although there was no sign the crop was under stress. The rain that came in late May and early June was really quite timely and we beefed up the T3 spray application as a result.”

NDVI images showed the east side of the field as more even prior to T1, while ‘striping’ found in May and June was “fairly subtle” and not related to the treatments, according to ADAS project manager Susie Roques. “From mid-July, the NDVI appeared slightly higher in the three BASF tramlines, suggesting that the BASF treatment helped to delay senescence,” she notes.

Richard agrees. “Up until the end of June, you couldn’t really tell the difference. But in first half of July, the Revystar plots stayed green for a good ten days longer – it was a noticeable difference. What’s more, the plants were green down to leaves four and five, while in the farm standard plots, these had senesced.

“It was similar to the greening effect we’d seen in the Teagasc trials during a trip last summer to Ireland, but those plots had high levels of septoria. The difference with us is that our extended GLA wasn’t down to disease – I’ve never seen that effect before.”

During grain filling, around 20% of sunlight is intercepted by the ear, 40% by the flag leaf, 20% by leaf 2, 10% by leaf 3 and the remainder by lower leaves or the soil, explains Susie. “So maintaining a high proportion of the upper leaves green for as long as possible is key to realising a high yield.

“But the only disease observed when we assessed the crop in July was septoria, present at very low levels up to the flag leaf. There were no significant differences between treatments in disease severity or GLA from the July tissue assessment.”

These did become apparent at harvest, however. “We excluded the headland and combine runs containing wheelings, which adjusted the yield in the farm standard treatment area to 13.89t/ha,” she reports.

“The modelled effect of the BASF treatment was to increase yield by 0.99t/ha, relative to the farm standard, which is a statistically significant difference. In this trial a yield difference of only 0.44t/ha was needed for statistical significance at the 90% confidence level.”

It was a result noticed during harvest, observes Richard. “You couldn’t really see the difference between tramlines, but when the combine went through, it filled up the tank faster in the Revystar strips, so we knew these would perform better.”

The YEN analysis of samples taken from the field close to harvest reveals the Revystar-treated plots had a very low ear population. But this was more than compensated by a high number of grains per ear and a high specific weight. Early to flower and late to senesce, the YEN analysis suggests there was an extended grain-fill period.

“It looks as though the crop yield was somewhat constrained by a relatively low ear population, which is set early in the year, so that’s something to look at addressing in future. But the crop fared well during grain fill, and the higher yield from the Revystar plots suggests that’s where the new chemistry really helped,” notes Richard.

“But we mustn’t overuse Revystar, or resistant populations will build. So I think the best timing is at T1 as the early protection will put the crop in a good place. Then we’d only need to use the product twice if the season really turned against us,” he concludes.