Whether knowledge on field variability is something you know from experience or is contained in vast amounts of historical data, it must be captured before it can be used to improve productivity. CPM seeks advice on how.

If you put flat-rate inputs on to a variable field, you’ll get variable results

By Tom Allen-Stevens

When you were sitting on the combine seat, did you notice that good patch of wheat, where the crop bunched up nicely on the cutter bar and you had to drop the speed to help it through? Or that curious thin patch that needs further investigation? It would be good if the crop came in evenly – preferably more bunched up than thin and patchy.

“I haven’t come across one UK arable field that doesn’t have some degree of variation from one end to the other,” points out Lewis McKerrow of Agrovista’s Plantsystems.

“That may be down to soil type, nutrition, whether it’s north or south-facing, weather, water-logging or a host of other issues. But if you put flat-rate inputs on to a variable field, you’ll get variable results.”

The difficulty is turning that variability into something meaningful, he continues. “Every grower knows their fields, but many don’t have any data that quantifies how the yield potential within them varies. Equally, there are many growers who have amassed vast quantities of yield map and soil data – so much, they’re suffering information overload and don’t know what to do with it.”

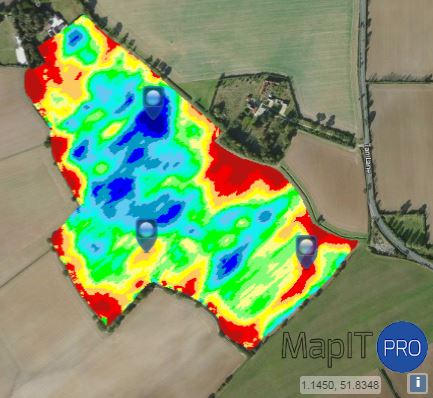

The aim with MapIT Pro has been a package that is simple enough to use, but also be powerful enough to handle a lot of data and process it quickly

The software exists to manage this data, he says. What’s more, it can help you interpret the information and turn it into variable-rate recommendations for a fertiliser spreader or seed drill. There are a number of these platforms now available, tailored to the needs of UK arable farmers. Which one you pick will largely depend on who carries out your agronomy, but it’s important there’s a level of interpretation that’s carried out from the outset, notes Lewis McKerrow.

“The first step is to sit down with your agronomist and decide what you want to achieve. Then it’s a question of pulling together the data you have that interprets your fields’ variability, and turning these into management zones.

“You don’t need a lot of fancy data, though – a good software package will allow you to create your own zones and digitise the information that’s in your head.”

How detailed you make these zones is up to you – the software should allow you to split your fields into, say, three zones (low, medium and high-yielding areas, for example) right up to a dozen or more, and it should let you to manipulate them.

A good software package will allow you to create your own zones and digitise the information that’s in your head, says Lewis McKerrow.

“When you create your zones, the human touch is important,” he adds. “Some data needs some tidying up – where the combine turns at the end and half-header cuts, for example.”

So ease of use is crucial, he stresses. “Our aim with MapIT Pro – the software platform we use – has been to take the pain out of the process. It has to be simple enough to use, so that you can get results from it without spending too much time getting accustomed to the software. But it should also be powerful enough to handle a lot of data and process it quickly.”

With any software package, there’s an element of setting it up, he explains. “You need to tell it where your fields are and to mark the boundaries. You can usually import boundary data obtained from the Rural Payments Agency or from a third-party mapping provider. There is also the simple option of drawing the boundaries over a Google maps background – this may take some time, but it’s a one-off process.”

Compatibility with other proprietary systems is important, so that data can be seamlessly imported from other on-farm equipment. “These days, that’s rarely a problem, so MapIT can import direct from a Claas combine, for example.”

Generating application maps is carried out automatically, with a few criteria, such as average field rate, set by the user. “It’s useful to be able to apply different layers and slide them in and out so you can refine your application map.”

Another valuable function is to be able to create markers for areas that need further investigation. “In MapIT Pro, these can be exported to the app on a tablet or smartphone, so you can pinpoint in-field sampling,” notes Lewis McKerrow.

Finally, if you get stuck, help should be at hand so you can complete your task, he adds. “We have a small but experienced team who offer technical support over the phone or can remotely log into your computer and resolve most issues. The aim is that you spend as little time as possible in front of a computer so you can focus on optimising the potential of your crops.”

- A subscription to MapIT Pro Advanced, that allows data to be imported, application maps exported and syncs with tablet or smartphone-based app, costs £250/year.