With the date now set for Britain leaving the EU, arable farmers may be among the first to feel the effect it may have on markets. CPM assesses the likely impact.

The UK could be facing currently unknown barriers to trade with the EU.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

Before you pick up the phone to your seed merchant, consider this: the seed you’re about to buy will form the crop you may be selling after Britain has exited the EU. For the first time since the second world war, no one knows what the trading terms will be for UK arable crops as the seed for those crops is being planted, and in theory, there may not be a market for them at all.

“Brexit is the biggest unknown everyone’s coming across – we still have uncertainty as to what will happen,” says Cecilia Pryce, senior market analyst at Openfield. “Realistically, by April 2019, the UK could be facing currently unknown barriers to trade with the EU, while also facing full exposure to global grain prices.”

On the plus side, agriculture isn’t the only industry affected, she notes. “Farmers face just as much uncertainty as those who are buying their grain, so as 2019 approaches, a good knowledge of your market and a good relationship with your merchant will become more valuable.”

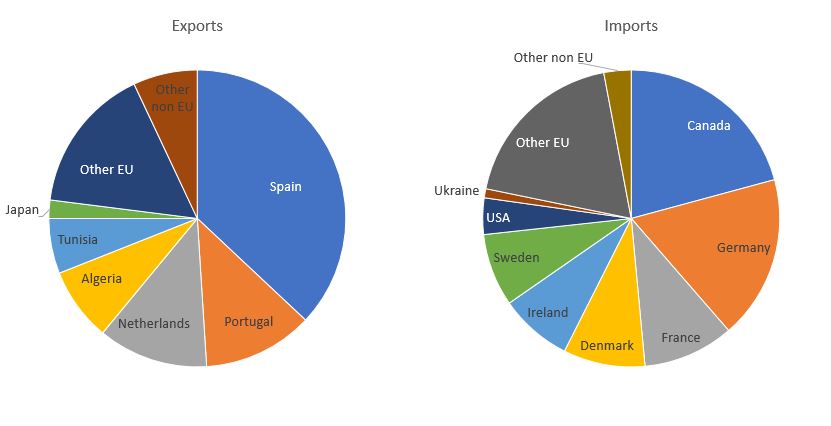

UK wheat and barley imports and exports

Source: HMRC

So what do growers know about their market and how Brexit will affect it? AHDB has put in some work here and produced a series of ‘Bitesize’ Horizon documents, one of which summarises what Brexit may mean for cereals and oilseeds producers.

Around 80% of cereals and 94% of oilseeds exports are traded with the EU. If the UK finds itself outside a free-trade agreement, tariff rate quotas (TRQs) allow a specified quantity to be imported into the EU at a low tariff, which for wheat is currently €12/t. Once the quota’s reached, the tariff’s jacked up to €95/t for wheat. Oilseeds are tariff-free.

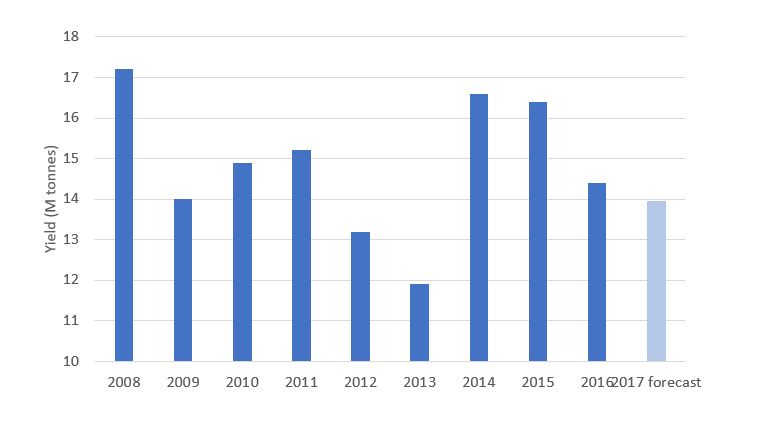

UK wheat production

Source: Defra and AHDB early bird survey

There’s been a reduction in the area of wheat such that in the current trading year, and for harvest 2017, the UK is likely to import as much as it exports. This should put the market as a whole into a position of some stability, although much depends on individual trade agreements.

The other unknown is maize, notes AHDB senior analyst Helen Plant. “In the feed grain market, wheat will compete directly with maize, and that’s a challenge.” Maize is the world’s most widely grown cereal, and annual consumption has just topped 1bn tonnes. UK wheat would struggle to compete with maize on the feed grain market as maize is inherently more efficient.

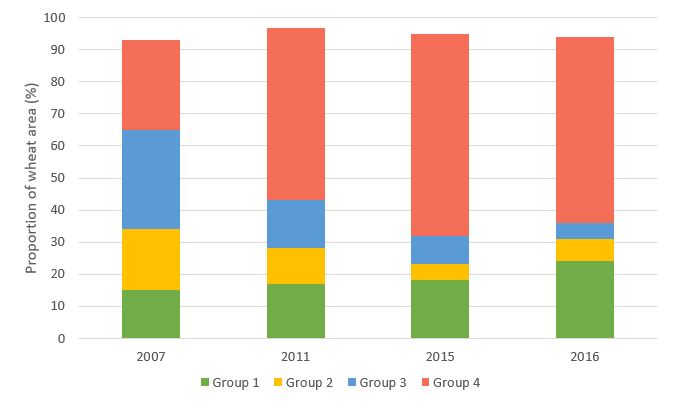

UK wheat variety profile

Source: AHDB planting and variety survey

Imported maize into the EU must meet strict criteria on GM crops and there’s a TRQ of 280,000t. UK imports come almost exclusively from France, but increasing volumes are coming from Ukraine and Eastern EU countries. The effect of maize on feed grains post Brexit will depend heavily on trade deals done with maize-exporting countries and the stand the Government takes on GM crops.

“If we go for a free market, we could be vulnerable to large imports of maize if price and quality allow,” notes Cecilia Pryce. “We’d have to take the rough with the smooth – it would hit the feed grain prices for arable producers while allowing for exports of better quality wheats, but could also result in cheaper feed for livestock farmers.”

Wheat imports vary from 7-20% of domestic demand and are predominantly from Germany, Canada and France, much of which is high protein wheat, which is not largely produced in the UK. These countries also act as a source quality and feed wheat in years when yields come up short or weather reduces quality. Lifting import restrictions may have little direct effect on the milling wheat market, but some processed cereal imports into the EU carry a higher tariff. So if Brexit resulted in a change in trade flows, this may have a knock-on effect on the domestic cereals market.

“If you have a domestic market for your grain, it’s worth thinking about how dependent that end user is on the export market, and how vulnerable that market might be post Brexit,” points out Cecilia Pryce.

Two thirds of barley exports go to the EU, and both feed and malting barley are exported. There’s a thriving domestic demand for malting barley, especially for distilling malt, although much of this is exported – whisky is the UK’s single largest food and drink export.

“If there’s a strong market for a commodity, traders will soon learn how to embrace any trade barriers that are put in place,” says Cecilia Pryce. “There’ll be a market or price adjustment, but trade will recover if it’s commercially viable for all parties.”

Oilseeds trade at world market levels, but there are always invisible barriers in every sector,she notes. “These can come in the form of GM and phytosanitary restrictions, that could limit our exports to the EU while also affecting imports. The amount of paperwork and justification needed shouldn’t be underestimated – anyone thinking regulation will be relaxed is sorely mistaken. If anything, the requirements to prove low chemical residues, toxins and similar justifications could increase if the UK is to continue to trade goods with the EU.”

But for the most part, the effect of the majority of market mechanisms will have little overall impact on the market in the medium to long term, she believes. “If you want to limit your exposure, grow for a local market and get to understand that market better. If the main destination for your grain is a port then it may become more complicated – what size ships can it accommodate and what are their main destinations? Proximity to the EU won’t change but trade routes and quality requirements may.

“But the reality is that commodities trade on price and quality, and Brexit won’t change that – we have been trading at world market prices for many years. There may be potential added costs, although this could affect EU businesses we currently deal with, just as much as farmers in the UK. What we need to prepare for more than anything are some years of uncertainty, extra work and delays, but we should embrace the changes that come our way.”