There’s plenty of arable land where ryegrass causes the same sinking feeling as a field growing a carpet of blackgrass. CPM gleans some insight on its control.

If we don’t make changes we probably won’t be growing wheat at all in ten years.

By Lucy de la Pasture and Rob Jones

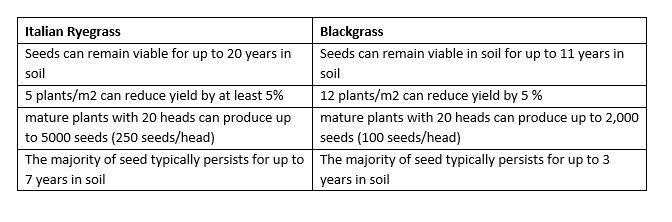

Italian ryegrass may not be the focus of as much research, discussion and noise as its cousin blackgrass, but looking at some basic facts, it’s easy to see why it can cause problems. Just 5 plants/m2 can cause a yield loss of at least 5% with some reports of up to 15% yield loss. Each plant commonly produces 20 heads which can shed up to 5000 seeds per plant, some of which can remain viable for up to 20 years but typically persists in soil for up to seven years.

The other feature of Italian ryegrass is something of a discussion point. There’s a widely held view that ryegrass has a more protracted period of germination than blackgrass, but the limited research that’s been done doesn’t completely support this common belief, explains Dr Gordon Anderson-Taylor of Bayer.

Gordon Anderson-Taylor believes early autumn emergence of ryegrass may go unnoticed.

“Work by Stephen Moss showed that the pattern of ryegrass emergence was very similar to blackgrass, with the majority emerging during Oct and then smaller numbers through till spring.”

But people who are working with the weed week in week out, think that the protracted emergence is a definite trait. So what’s going on?

“In the early stages, ryegrass and wheat can be quite tricky to tell apart, so people may not notice the level of autumn germination. But as the season progresses, emerged ryegrass is easier to spot. In a situation where delayed drilling is coupled with robust pre-ems, it’s those plants that germinate in the later part of the natural germination window that will be spotted and cause farmers problems.”

Kent farmer Ben Binder’s experience from the field supports the view that enough ryegrass germinates after Oct to cause more than a nuisance in crops.

“It seems to have a less predictable germination pattern than blackgrass. It germinates throughout the autumn and into spring. I recently walked an OSR crop and found freshly germinated ryegrass in it. Any disturbance seems to set it off.”

Ben Binder grows winter wheat followed by either OSR, spring oats, spring beans, spring wheat or linseed on 785ha of land and is familiar with the ins and outs of both weeds.

“On the one farm, delayed drilling works a treat for blackgrass, but against ryegrass it isn’t that useful. We sow wheat in the middle of Oct, which allows us to clear up some of the ryegrass but you don’t get the same improvement as blackgrass.”

Establishment is followed by a robust herbicide programme of Trooper (flufenacet+ pendimethalin) and Defy (prosulfocarb) followed by Liberator (flufenacet+ diflufenican) to prolong protection and Atlantis (mesosulfuron+ iodosulfuron), provided the ryegrass is still at the 1–2 leaf stage where it is vulnerable.

Ben Binder now finds many crop and agronomy decisions being dictated by ryegrass control. “We’re having to use double break crops and focus on crop competition. A competitive crop – especially spring oats – is really the only thing that will keep up with ryegrass and where there are large populations, even then it’s debateable whether they do a good enough job.

“We fully accept that our wheat yields will suffer growing oats followed by wheat because the oats scavenge out so much nitrogen, but if we don’t make changes we probably won’t be growing wheat at all in ten years.”

Across the rotation, the main focus is on reducing soil disturbance in crop to control ryegrass.

“Last spring I thought the propyzamide did a stunning job in the OSR, however the tramlines and surrounding area were full of ryegrass as soil disturbance had taken place with continual passes allowing churning of seed. I find that the more you can move the soil out of crop with ryegrass the better, but not within a month of drilling,” he comments.

He’s recently invested in a Weaving low-disturbance drill and is pleased with the results so far and reinforces his view that the less disturbance the better. Prior to establishing a spring crop, Ben Binder uses cultivation to encourage germination and exhaust seed supply, although he realises that a large seed-bank may reduce the benefits of this approach.

Further north in Yorks, ryegrass is equally problematic – especially on land with a history of livestock and grassland in the rotation. On one farm, just south of Wakefield, Bayer is helping a farmer take the fight back to ryegrass with a herbicide trial on some difficult land.

“This is our second year of trials on this farm – last year we seemed to have good control from pre-em and early post-em herbicides but, like on lots of farms, the weeds recovered and were quite bad by May,” says local Bayer commercial technical manager, Adam Tidswell.

Richard Gill is the farmer of the land, with a rotation of OSR, first and second wheat then spring and winter barley. The rotation is designed to maximise ryegrass control and provide a good entry for OSR and wheat. Because of the cool, damp conditions in this part of the country Richard Gill finds he can only be sure of a good establishment of OSR after winter barley but he requires spring barley for ryegrass control.

“We’ve been fighting it for years. Second wheats always caused problems so it has to be winter barley or spring barley because it’s the only thing that can compete with ryegrass,” he says.

“Some of land is quite heavy with poor drainage – we’re taking steps to rectify this but I believe that very wet soils have held back our herbicide programme.”

He typically uses Liberator or Movon (flufenacet+ diflufenican+ flurtamone) with prosulfocarb followed by either Pacifica (mesosulfuron+ iodosulfuron) or Atlantis in problem fields and along headlands.

He’s most interested in seeing how soil moisture affects pre-em performance in trials.

“Where it’s very wet, my experience is that residual herbicides don’t work properly. The trial is taking place on one of the wetter fields so the results should be interesting.”

Agrii agronomist Rob Daniel has advised Richard Gill for five years and has seen the problems ryegrass brings. “Some of the ryegrass has resistance to post-em chemistry so we have to get the pre-ems and cultural controls right,” he says. “Drilling has been pushed back as late as we dare in this part of the world and he’s started using a mustard cover crop ahead of spring barley.”

Looking ahead to this spring, Rob Daniel thinks control programmes have performed well so far. The autumn was ideal for crop establishment across the board and even late drilled OSR looks good. In the winter wheat, the aim is to get out and apply a post-em as soon as possible, he comments.

“To beat ryegrass, I think it’s best to apply the post-em before any spring fertiliser – there’s no point feeding ryegrass. Most of the resistance is the EMR type, so anything which makes ryegrass larger before your post-em will reduce the level of control.”