The Smith Period has been the lynch pin behind late blight programmes for the past 60 years but recently its reliability has been under question. The new benchmark for predicting blight outbreaks has been a long time coming but was at last unveiled at AHDB’s Agronomist Conference in December.

The Smith Period was not performing equally well in all parts of the country.

By Lucy de la Pasture

Since the new aggressive blight strains, 13_A2 and 6_A1, became dominant just over ten years ago, predicting blight has been a concern for potato growers every single year, agronomist and specialist potato adviser for Spud Agronomy John Sarup told delegates, who welcomed the updated guideline, named The Hutton Criteria.

“A tool for identifying high risk periods of disease development is crucial to help us protect our crops and give us the confidence to schedule control activities at the right time, to the right level. In recent seasons, blight has been found on crops even before any conventional Smith Periods have been recorded, meaning the current tools and systems just weren’t reliable enough to support precise decision-making.”

The Hutton Criteria has been developed by AHDB-funded PhD student, Siobhán Roísín Dancey, who has been conducting her research at the James Hutton Institute, in collaboration with supervisors Peter Skelsey and David Cooke.

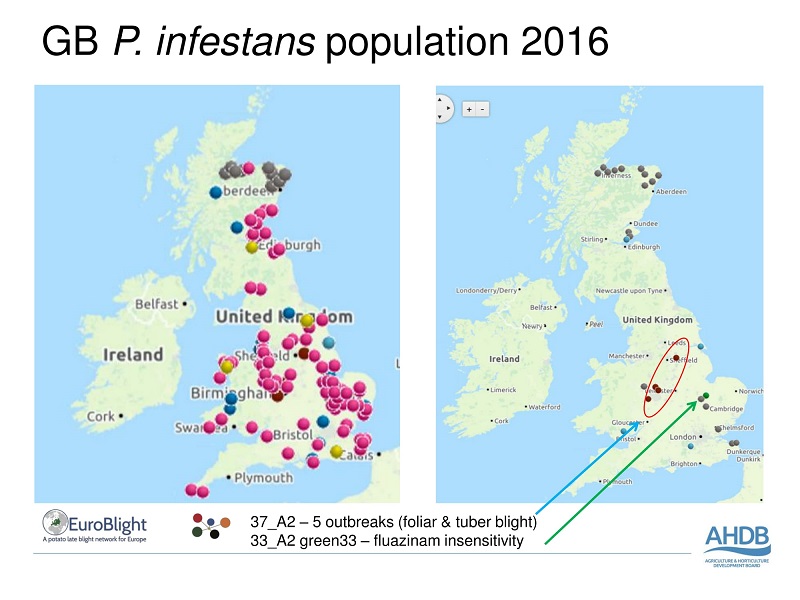

Novel strain 37_A2 appeared last year and may be one to watch.

Source: AHDB-Potatoes & Euroblight

She examined relationships between reported outbreaks and recorded Smith Periods and performed controlled environment experiments to determine new thresholds indicative of high blight risk – in light of the fact the more aggressive strains of blight are able to complete their life cycle faster.

“Previously, the collective reasoning was that a lowering of the temperature threshold would provide earlier indication of blight pressure, and certainly some commercial prediction systems adjusted their operating criteria in line with this in efforts to improve the services available to growers,” said Siobhán Dancey.

“While our data did demonstrate some improvement with this approach, it wasn’t a pronounced effect. We established that when infection occurs below the 10⁰C threshold, the rate of disease development is decreased.”

Similarly, reducing the relative humidity threshold to below 90% resulted in a drastic reduction in the amount of blight infection, which indicated that the relative humidity threshold in the Smith Period remained valid.

“We found a reduction in the period of relative humidity at 90% (or above) down to six hours (from the present eleven) proved the most striking match for the conditions which resulted in an actual blight outbreak,” she explained.

Putting the findings to the test against over 2000 historic reports of potato late blight outbreaks, the Hutton Criteria demonstrated a significant overall improvement in performance over the Smith Period, with 69% of historic blight outbreaks receiving an alert compared with just 41% under the old system.

“Past records revealed that the Smith Period was not performing equally well in all parts of the country and the Hutton Criteria has eliminated this issue,” she added.

AHDB-Potatoes chair Fiona Fell described the Hutton Criteria as a step-wise improvement on the Smith Period when asked whether it will endure.

“How long it remains effective will depend on the development of new blight strains but it has been proven to work on the current blight population,” she commented.

Encouraging news for British potato growers is that, in the main, blight populations have remained relatively stable in 2016, with very little diversity. The blight strain 6_A1 remained dominant, along with a lower population of 13_A2, indicating that the blight population is mostly clonal, Dr David Cooke told delegates.

Making a return to the population screen in 2016 was 23_A1, a tomato-adapted strain and there was also a return of the 33_A2 strain which has been absent for the past three years.

“33_A2 or green 33 is the strain of blight in which insensitivity to fluazinam has been recorded and one isolate was detected in 2016, so it hasn’t gone away. It’s a reminder to exercise caution in blight programmes because routine use of any active ingredient in blocks may lead to the development of resistant strains,” he said.

Last season there was also the arrival of a novel strain, 37_A2, which was found in just a few outbreaks.

“We don’t know much about 37_A2 yet but it was detected in five samples of both foliar and tuber blight. It’s a strain that has also been found in France, Netherlands and Belgium in 2015 and 2016 and its traits are being studied under the IPM-Blight 2.0 Project, which aims to link genotypes to phenotypes to determine aggressiveness, virulence and fungicide resistance. We’ll know more about it by the start of this blight season,” he said.

Looking at the data from the rest of Europe, novel clonal strains 37_A2 and 36_A2 have emerged over the past two seasons and may be ones to watch. 70% of the blight population is clonal with 20-30% of populations more genetically diverse, explained David Cooke.

“The clonality shows that most of the inoculum survives over the winter in tubers. Most primary inoculum is generated locally so it remains vital to manage discard piles and volunteer potatoes as the first line of defence against blight,” he reminded growers.

Target seed and soil treatments for black scurf control

New research highlights the need for seed treatments and good cultural practices in controlling Rhizoctonia.

Rhizoctonia solani is the principal cause of stem, stolon and root canker and manifests on tubers as black scurf, and in some instances, elephant hide, symptoms of which are familiar to all potato growers.

Rhizoctonia diseases have a considerable economic impact: in-field losses of up to 30% have been recorded. Once non-saleable losses through tuber deformity, black scurf and other blemishes are included, its true impact can be far greater.

Due to these losses, it’s a disease that attracts significant research investment around the world. In a paper published last year in the journal Potato Research, researchers from the James Hutton Institute (JHI), Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC) and the Food and Environment Research Agency (FERA) considered the relative importance of seed and soil-borne sources of inoculum in causing disease and whether there’s a measurable relationship between inoculum levels and black scurf in commercial crops.

Previously, results from research into the relative importance of seed and soil-borne sources of inoculum were inconclusive. In contrast, findings for other diseases, such as black dot, identified soil-borne inoculum as having a greater effect on progeny tuber disease than seed-borne inoculum, explains Dr Jennie Brierley, a researcher in potato pathology and diagnostics at JHI and lead author of the paper published in Potato Research.

The time taken to reach emergence can affect disease severity with soil temperature and seed age considered important variables. Other studies have found soil moisture to be important while soil type is another factor that could be better understood.

Some soils, for example the soil at the East Yorks site sampled in the latest published research, showed signs of being suppressive, meaning that despite the presence of inoculum both pre-planting and post-harvest, no disease developed on the tubers. Conversely, inoculum was consistently undetectable from the inoculated Fen topsoil at both pre-planting and post-harvest, yet black scurf developed on the progeny tubers (22% incidence).

According to Dr Jennie Brierley, the study highlights the complex interaction of factors that promote disease and the limitations of the test used in identifying infested land.

“When a range of soil and compost types were infested with a small amount of inoculum, pathogen detection using real-time PCR was inconsistent both between the soil and compost types and sometimes between replicates.

“Whilst detection was consistent within the replicate extractions in some soils, it appears that detection of low levels of inoculum was impeded in others, in the JHI compost. As low levels of soil inoculum can cause disease, if pre-plant soil testing for rhizoctonia is to be made reliable enough for widespread use, improved sampling strategies need to be further explored.”

What does this mean for growers intent on reducing the incidence of rhizoctonia in commercial crops?

“In the absence of a breakthrough product or significant advancement in our understanding of the disease, good control comes down to attention to detail. The ‘prevention is better than cure’ metaphor is an apt assessment of the situation,” says Scottish Agronomy’s senior agronomist Eric Anderson.

Previous studies have highlighted the need for good field hygiene in limiting inoculum carryover, while moisture stress (too much and too little) has also been found to be influential.

“Good field hygiene applies across the rotation, especially as there is no known ‘cleaning crop’ for reducing rhizoctonia. Studies have highlighted the importance of organic matter in facilitating pathogen survival, with manure, cereal and potato trash, or fields with a recent history of grass or potato volunteers all containing higher levels of the rhizoctonia pathogen,” says Eric Anderson.

“The effect of moisture is also significant and is likely to be a result of complex interplay with soil type and other environmental factors. Some studies have found moisture levels to have little or no effect on stem canker development, but do influence black scurf and elephant hide. This warrants further investigation,” he adds.

Aside from avoiding planting seed straight out of cold store or into cold, wet soils, seed and in-furrow treatments are the first line of defence.

“Tuber treatments remain the best means of combatting seed-borne infection, but performance varies greatly between products,” says Eric Anderson.

“Monceren (pencycuron) is the obvious choice of tuber treatment as it offers greater flexibility in application than flutolanil powder, which can only be applied using an automated on-planter applicator, and fludioxonil liquid, which must be applied to dormant tubers within three-months of planting.”

All research however, supports the need to apply seed treatments, where necessary, in sequence with in-furrow methods of protection, he adds.

“Where there is known to be a high incidence of soil-borne inoculum, it’s often not enough to rely on a single means of protection. An in-furrow application of Amistar (azoxystrobin) should be considered as trials show that when used in combination with Monceren, the severity and incidence of black scurf is significantly reduced,” says Eric Anderson.