Light leaf spot is a disease that last year caught many growers with their trousers down. CPM asks the experts why it’s becoming more prevalent and what’s the best way to control it.

Once infection has occurred, the disease continues to cycle.

By Lucy de la Pasture

A decade ago, light leaf spot was largely an important disease in Scotland and the northern reaches of the UK, but was less widespread in England. In recent years that seems to have changed, with the disease popping up all over the country and superceding phoma as the main disease concern prior to Christmas. So what’s going on?

ADAS plant pathologists, Faye Ritchie and Julie Smith, point to a number of factors that are implicated in the rise of LLS across the nation. One of those is the massive increase in oilseed rape area which occurred in its glory days, when OSR prices hit a very healthy £450/t.

LLS has a long latent phase so early symptoms are difficult to see, especially on wet leaves and the disease can also often initially appear just in patches.

“OSR has doubled in area from the 1990s and LLS is a disease where the previous crop fuels the epidemic for the following year,” explains Faye Ritchie. “The fungus responsible for LLS produces ascospores on crop debris which are airborne and provide the inoculum for autumn crops in the ground. So the greater the crop area, the more likely inoculum will be present to infect subsequent crops.”

But it’s not just down to an increase in crop area. The weather’s also changed and last year in particular was very favourable for LLS development, explains Julie Smith. “Unlike phoma, LLS is polycyclic, which means that once infection has occurred, the disease continues to cycle.

“So there’s reinfection occurring from conidia which are produced in acervuli on infected leaves and spread by rain splash to new leaves. We suspect that infection can also progress internally within the plant and may subsequently appear on buds before they emerge in spring.

“Some of our early work showed that LLS spores need 17 hours of leaf wetness for infection of the leaf to occur and then enters a relatively long latent phase of approximately 260 day degrees, where no symptoms are visible. This means that the latent period could be as short as 17 days if mean daily temperatures are around 15°C.

“The warmer and wetter the weather, the more quickly the LLS fungus will cycle, which is why the challenge was so high last season, although the pathogen is inhibited by high (>21°C) summer temperatures,” she says.

On looking closely at the lesion, it’s possible to spot tiny spore droplets (acervuli), usually around the outer edge of the lesion and often on both leaf surfaces.

If that sounds like a familiar pattern of disease, it’s because LLS is akin to septoria in wheat in terms of infection and spread. So does that

mean that the principles of septoria control can be applied to LLS? That’s a question that hasn’t been fully answered yet as researchers play catch-up to find the best control strategy. But there are things that growers can do to limit the severity of LLS in their crops, believes Julie Smith.

“The approach to LLS needs to be an integrated one and that means choosing a variety with a degree of resistance to LLS is a good first step,” she says. “It’s a tactic that wheat growers are employing as a matter of course but it doesn’t tend to be the first thing that growers look at in an OSR variety.”

It’s an area that plant breeders are working on, with a couple of the newer varieties on the AHDB Cereals and Oilseeds East/West Recommended List, Alizze and Elgar, having a score of 7 for LLS and some promising candidates in the pipeline. But the vast majority have ratings of 5s and 6s, she points out.

“Varieties with a higher resistance to LLS buy you flexibility because they help keep LLS levels low over the winter period before a spring spray can be applied. This is particularly relevant when the weather is catchy or the field won’t travel, so winter spray timings slip.

“Effectively a resistant variety will ‘shift’ the epidemic through time because there’ll be less cycling of the disease and fungicides can be applied in a more protectant, rather than than curative situation. That means there’s less selection pressure for fungicide resistance as well,” explains Julie Smith.

With crops now in the ground, it’s a case of identifying which ones are at highest risk of LLS infection and keeping a close eye on them. There’s likely to be plenty of LLS inoculum around this autumn and with cool summer temperatures another factor favouring the disease, it’s all stacking up to have potential to be another high LLS season, adds Faye Ritchie.

Current advice is to apply a fungicide from late Oct onwards or when the disease is first seen in the autumn. With no spray threshold for LLS before the stem extension growth stage of the crop, further fungicide applications should be considered from Jan/Feb onwards when new symptoms are seen, she advises.

This relies on regular crop inspections and more crucially, identification of early symptoms of LLS. Early infection is something that both experts agree is difficult to spot and may be a contributing factor where LLS is poorly controlled.

Symptoms to look out for are pale green lesions which tend to appear during Nov/Dec. These later take on a mealy appearance without a defined edge. On looking closely at the lesion, it’s possible to spot tiny spore droplets (acervuli), usually around the outer edge of the lesion and often on both leaf surfaces.

The spore droplets are white and look a little like grains of salt. In the early stages of the disease the spore droplets may be present without causing any discolouration to the leaf, points out Julie Smith. “Early LLS symptoms are difficult to see, especially on wet leaves. The disease can also often initially appear in patches across the field so can be missed when field walking.”

But because of the long latent phase of the LLS disease, infection is occurring much earlier in the life of the crop than when symptoms are first seen in the field, reminds Julie Smith.

The easiest way to assess crops for the presence of LLS is to incubate leaves by placing them in polythene bags and storing them at room temperature for up to four days, which will accelerate symptom expression, she advises.

One of the problems for southern growers may be an over-emphasis on targeting phoma control in the autumn, with LLS being unintentionally missed, adds Julie Smith.

“The first phoma spray should protect against LLS, but offers a limited period of protection, so unless there’s a follow-up spray, the disease can develop. As a rule of thumb, aim to apply a second spray when re-infection occurs, which can be anywhere from 4-10 weeks later, depending on weather.”

It’s part of the conundrum that growers face – the reality is that often ground conditions can put the kybosh on late autumn fungicide applications. Last season proved that point and in some cases LLS control was further compromised by not applying a second autumn fungicide because growers were waiting for the right time to apply Kerb, according to Bayer’s combinable crops fungicide product manager, Will Charlton.

“There’s a problem with this approach of waiting to apply the second fungicide with Kerb,” he points out. “Fungicides need a dry leaf so by the time conditions are right for Kerb to go on, the fungicide often has to be omitted because blackgrass is the priority.

“40% of the UK OSR crop didn’t receive an autumn fungicide at all last year and of the remainder, only one in five crops gets two autumn fungicides. Even where one fungicide has gone on, even if it’s one of the ‘stronger’ ones on LLS, no fungicide can provide protection over the three to four-month window needed over the winter period. So LLS will get in,” he warns.

Typically, agronomists do plan for two autumn fungicides targeting phoma but very often the second spray doesn’t go on. “It’s important to apply a robust treatment of prothioconazole as the early spray because the second spray can’t be guaranteed,” he adds.

And that’s something both plant pathologists agree with. “If you can reduce inoculum in the crop early, then there’s less disease pressure on the next leaf level which can lead to a reduction in the epidemic, with potential benefits later in the season,” says Julie Smith.

One pressing question that remains unanswered is when exactly should control start? In wheat there’s no justification to control overwintering septoria, with programs beginning at GS30. We do know autumn fungicide application can be beneficial for control, but whether or not targeting the ascospore phase of LLS specifically in OSR is justifiable is unknown, points out Faye Ritchie.

Bayer commercial technical advisor, Jon Helliwell says that research last season showed that inoculum was plentiful earlier than you might expect, even as the crop was just emerging.

“The results of the AHDB and Bayer-sponsored spore-trapping initiative, coordinated by Weather INnovations Consulting (WIN), showed significant ascospore events in 2015 from Aug and right through the emergence phase. Crops were under threat from the moment they came through the ground,” he explains.

According to Dr Neal Evans, plant pathologist at WIN, it was hoped that spore trapping would help produce a date-driven forecast for LLS, similar to the one produced for phoma, but the polycyclic nature of LLS means that the situation just isn’t as clear cut.

“It quickly becomes very chaotic at field level where LLS is concerned,” he explains. “Within the crop there are microclimates within the different leaf layers and different areas of the field. Because the disease can keep cycling, it’s also likely to be present at several different stages of infection. This is one of the reasons that LLS infection can appear as patchy in fields.”

The effect of disease pressure on different leaves and disease reduction at specific leaf timings is something that’s well defined in cereal crops but much less well understood in the OSR plant. Work has begun to look more at the leaf layers protected after fungicide applications at the five key OSR timings – autumn, late autumn, Jan/Feb, March stem extension and flowering – to help understand the influence of timings on disease control.

So how should growers be targeting LLS this autumn? On the one hand, just like for septoria, fungicides work best for LLS when used as a protectant rather than a curative treatment. The other side of the coin is that it’s not clear exactly when it’s economically best to start a programme.

There’s not enough evidence at the moment to suggest two autumn fungicides for LLS can be justified, though there’s likely to be some crops in some seasons that prove the exception to the rule, believes Julie Smith, adding that LLS epidemics vary from year to year.

“It makes sense that an application of a phoma fungicide with decent LLS activity is a good start to an LLS programme on a susceptible variety,” she says.

At Bayer’s Hinton Waldrist demo site in Oxon, last season the disease control programme commenced with a single 0.46 l/ha dose of Proline (prothioconazole) to protect against LLS and phoma and these plots overwintered far better than those left untreated.

“As LLS is polycyclic, we still had the disease in treated crops but significantly less than untreated crops. Results show that a well timed and robust dose of a fungicide with proven activity against both diseases, coupled with an agronomically strong variety, is the foundation for OSR disease control,” believes Jon Helliwell.

“With so little OSR straw baled, the amount of infected crop debris providing a plentiful source of inoculum is a concern going forward. Growers will be drawing up winter crop budgets and it might be wise to factor in split sprays or higher doses for those looking at single autumn treatments.”

One of the frustrating features of LLS control is that typically field performance of fungicides can be very variable, with control typically in the 40-90% range. Pointing to resistance as the reason for this is a simple explanation but probably not the right one in the case of LLS, believes Faye Ritchie.

“Fungicide performance very much depends on both the epidemic and the fungicide being used, with poor timing usually the root cause where fungicides appear not to be working well. Fungicides perform much better in protectant situations with less disease present than in what has become a highly curative situation,” she explains.

“We don’t yet have a good handle on where we are with azole insensitivity in the LLS population, but we’re in a position to learn from what’s going on in with septoria in cereals and have the opportunity to implement a strong anti-resistance strategy before it becomes a problem,” adds Julie Smith.

That means out-smarting the fungus by using resistant varieties along with mixtures of products, and those with different modes of action, SDHI plus azole will protect one another, she concludes.

Protected leaf layers

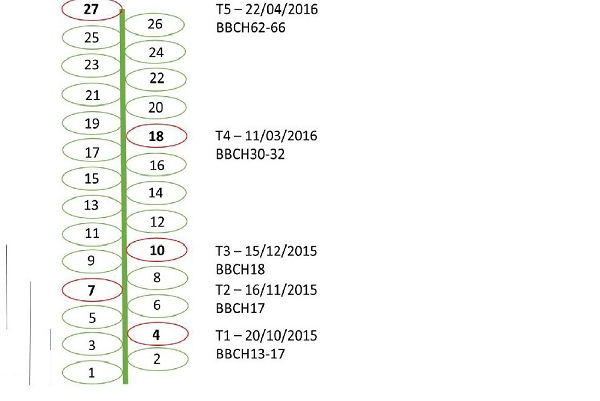

The figure shows a profile of an OSR plant from sowing to pod formation. Ovals represent leaves attached directly to th

e main stem with leaf 1 the first leaf to emerge after the cotyledons.

Red leaves (leaves 4, 7, 10, 18 and 27) were the uppermost fully expanded leaf layer at the time of the corresponding fungicide application. Fungicide application dates are shown to the right of the plant along with the growth stage at the time of each application. Growth stages are expressed in accordance with the BBCH scale. Vertical bars to the left of the plant show which leaves remained on the plant at the time of fungicide application.