So 2019 reaches its final furlong and 2020 beckons. It’ll be remembered for ever in many people’s minds for its wet back-end which proved the mother of wet back-ends.

So 2019 reaches its final furlong and 2020 beckons. It’ll be remembered for ever in many people’s minds for its wet back-end which proved the mother of wet back-ends.

At the moment we’re in the odd situation of having, on the one hand, the smug satisfaction of a reasonably full grain stores from a good harvest. But on the other hand, out in the field, prospects for 2020 look rather ominous – it’s a bit like the field of fat cows staring over the fence at a field of thin cows.

A kind winter and spring will do a lot to put things right, but it seems nowadays you seldom hear the words ‘kind’ and ‘weather’ in the same sentence. We were lucky here in as much that we had a lot of first wheats last year meaning an increase in spring-sown break crops hasn’t really rewritten the cropping programme significantly. That’s assuming we can get all the seed we want.

In hindsight I wish I’d grown a few acres of spring wheat as a weather-proofing measure but that’s hindsight wisdom. The old farming lore that you should never set too much store from the experience of last year is probably as apt this year as ever. But so is the observation that we’ve had yet another year with abnormal weather. What the heck ‘normal’ is nowadays seems a tricky question.

Weather is always a farming obsession and the endless analysis the internet provides just feeds the fixation. Radar maps are the worst here where I’m as aware of the weather in Cornwall as much as in Essex. Quite why I think I need to note weather conditions on the Isle of Bute I’ll never know but there I am poring over global reports that show its sunny in the Sahara.

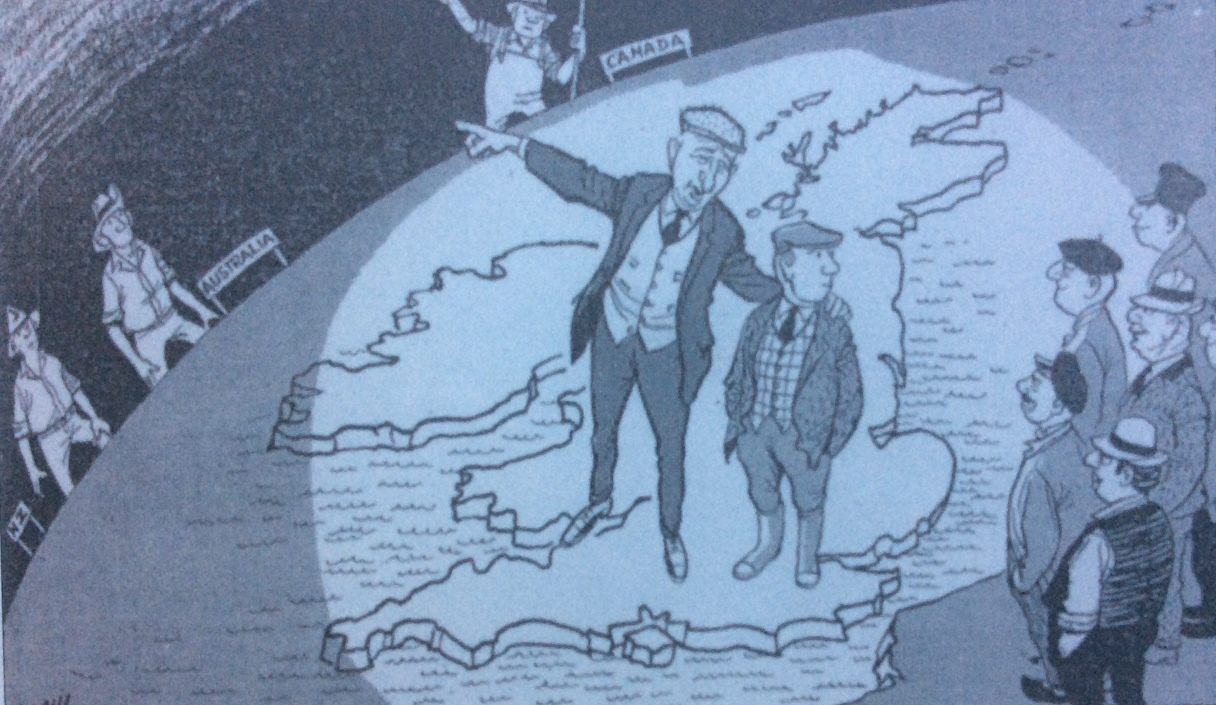

A cartoon from 1963 shows the then NFU president Harold Woolley urging a British farmer to “look West” not East when thinking of his farming future. Interestingly in the early 1960s, the NFU was against joining the EEC. Today this question as to whether our trade in food will look East or West is suddenly very pertinent again. Source: Farmer & Stockbreeder, 1963

Then there are the weather records where the Met Office tells you what sort of weather you’ve recently had, as if you didn’t know. These Met Office actual/anomaly maps reckoned north east Essex had ‘average’ rainfall. That doesn’t help explain why our 16ha potato field would now make an excellent place for a historical re-enactment group to play out the Battle of the Somme.

So we now look forward to a new and better year in 2020. I remember a few years ago in 2010 I chaired a conference called ‘20:20 vision – a look forward to see what the next decade might bring’. While contributors wisely foresaw things like increased commodity price volatility and increased resistance to fungicides and herbicides, no one predicted we might leave the EU with endless consequences for UK agriculture. If someone had predicted this, how many of us would have gone home and put some plan in place? No one would have because it was about as likely as the possibility of glyphosate being banned.

Guy Smith grows 500ha of combinable crops on the north east Essex coast. @EssexPeasant