Spring beans underscore a move into conservation agriculture for an East Sussex farm, and have even made a debut into its award-winning beer. CPM visits to taste and savour the approach.

We’re aiming to make the rotation as sustainable as possible, so why not try to add value to the beans?

By Tom Allen-Stevens

Take a sip of Long Blonde beer at the Plough and Harrow pub in Litlington, E Sussex, and it could well restore your faith in farming. It’s one of the leading lights of the Long Man Brewery, based in converted former dairy buildings at Church Farm, just 350 yards from the pub.

The brewery was founded by Duncan Ellis, who runs the family farm with his father and uncle, and started the venture in 2011 with business partners Stephen Lees and Jamie Simm. The malt for the beer is made entirely from RGT Planet and Propino spring barley grown on the farm and water’s drawn from an aquifer beneath the chalk downs on which the farm sits. Spent brewers’ grains are fed back to the 40-head of beef cattle, waste water is used to irrigate, hops are locally sourced and a bank of 100 solar panels helps power the brewhouse.

Duncan Ellis founded the Long Man Brewery which uses malt from barley grown on the farm with spent grain fed back its beef cattle.

“We brew traditional, Sussex beers which are very approachable to everybody,” says Duncan. “But what people really like about our beer is its story – the fact that the whole production system is contained on the farm.” Whether it’s the story, the taste or a combination of the two, the brewery has picked up a glittering array of awards, including a gold at last year’s World Beer Awards for its premium dark bitter Old Man.

Production from the brewery currently runs at around 2.5M pints per year, utilising around 140t of the farm’s spring barley. But this year, a small amount of the spring bean crop was introduced into the mash to make Long Man’s first ever bean beer.

“It was an experiment, using just 20kg of beans replacing 40% of the malt in a micro-batch. We produced 140 pints and took it to a number of summer shows, including Cereals and Groundswell. Interestingly, 90% of those who weren’t told it was brewed with beans liked it, while it was 50:50 if they were told beforehand,” reports Duncan.

The idea came from the farm’s agronomist, ProCam’s Richard Harding, who’s been helping the farm ease its way into conservation agriculture. “I went to Food Matters Live and came across a James Hutton Institute project, using fava beans to make beer with a brewery in Scotland. We’re aiming with Church Farm to make the rotation as sustainable as possible, so why not try to add value to the beans?”

Despite receiving insecticide for Bruchid beetle, the 2017 crop failed to meet human consumption standard, but that wasn’t a problem for brewing, notes Duncan. “The beans were processed by Suffolk-based Hodmedod’s. They were lightly crushed and an amylase enzyme was added before they were put in the mash. Brewing was a tricky process and we had no idea how the finished product would taste, but it’s been quite a success.”

This year, a further step has been taken towards the sustainable approach with part of this year’s spring beans, explains farm management consultant James Hamilton. “The farm has a problem with some of its grassland that’s unproductive. It went into environmental stewardship eight years ago and hasn’t really delivered anything for biodiversity nor nutritionally. With Brexit we don’t know what will happen with lamb, so we’re looking to integrate the livestock more with the arable enterprises – a mono-crop doesn’t make sense from a sustainability point of view.”

Bringing the leys back into the arable rotation creates a problem however, as ploughing them up destroys the root structure. “Much of it is on pretty poor clay soil, so we decided to try direct-drilled spring beans as a bridge crop on 12.5ha of grass, alongside the 50ha of conventionally established beans.”

The wet spring meant the crop wasn’t established until the fourth week of April, recalls Duncan. “The sheep were still grazing the field when we drilled with the Horsch Sprinter. The beans were tucked into the turf which remained intact. Then we sprayed off with glyphosate five days later.”

The result is a considerably reduced requirement for inputs, explains Richard. “The whole point of conservation agriculture is to mitigate cost. Here, one crop takes off as the other dies back, suppressing weeds, because of this we were able to use no residual herbicide. That means you can grow in wide, 250mm rows, resulting in less pest and disease pressure.”

The only chemical applied to the crop all season was the glyphosate at the start and one fungicide – it didn’t even receive a pre-harvest desiccant before it was harvested, without a hitch, with the farm’s New Holland CR9080 combine.

“In a normal year a desiccant would be needed for late weeds in conventional beans, which didn’t appear in this crop coming out of grass,” notes Richard. “You can apply the same approach with winter beans following grass. The one aspect to note is that direct-drilled beans tend to emerge slower than from a cultivated seedbed.”

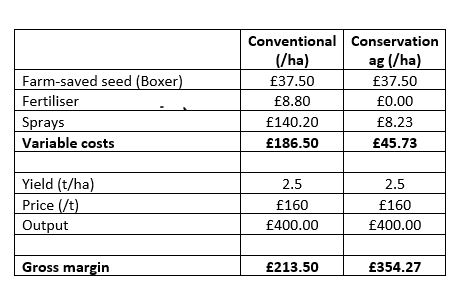

The farm’s conventionally grown beans received a full herbicide and fungicide programme, but the yield was the same in both cases, reports James (see table below). “The dry season brought us a disappointing 2.5t/ha, although the 2017 crop yielded almost 6t/ha, so we’re confident we’ll get a more respectable performance from up to 40ha we’re planning to take out of grassland next spring, given more favourable growing conditions.”

The main benefit, though, has been a perfect start for the following winter wheat crop, drilled at the beginning of Oct, says Duncan. “Beans always present soil beautifully for wheat, which was certainly the case in the conventional field. But the seedbed following the grass was stunning. If we’d left it and ploughed it this autumn, we’d have ended up with boulders and destroyed the structure. As it was, we made a shallow pass just to move the top 25mm as I was concerned about slots remaining open.”

The spring beans across the farm have made a notable difference to soil workability, he adds, and fit in well with the farm’s move towards no-till. “70% of the farm is now direct-drilled, and since moving to this system, we’ve halved fuel use. The Challenger used to be the mainstay tractor, but now I wonder whether we actually need a tractor with such a high draught capability.”

Rotation’s blurred and monoculture’s questioned in new approach

Spring beans form an integral part of Church Farm’s move into trialling conservation agriculture. There are three core features of the system: non-inversion of the soil, maximum use of diverse rotations and permanent ground cover for as much of the year as possible.

“We’re replacing steel with roots, nitrogen with nodules and fuel with photosynthesis. It makes so much sense and it’s a smarter way to farm,” says Richard Harding.

“But there isn’t really a fixed rotation as such. It’s a flexible approach that involves a lot of cover crops and quite frequently two crops within a calendar year. It challenges the established rationale of just one, single-species arable crop per year.”

So a cover crop including beans could precede a spring bean crop, for example. “Bean roots perform best when the soil is primed – the cover crop has a synergistic effect that ‘inoculates’ the soil for the cash crops. And it’s a myth that two crops grown in tight succession in this way encourage disease provided this is followed by a wider gap within the rotation.”

This year, 162ha of cover crops has been established at Church Farm, but there’s a particularly novel approach to oilseed rape. 200ha of the crop is in the ground, but 142ha of this has been sown in a mix with four other species.

“OSR is the one crop in the rotation that is non-mycorrhizal,” notes Richard. “So firstly, the other species provide a bridge for this important soil constituent. Vetch fixes nitrogen while linseed discourages pigeons. Phacelia’s roots do wonders for the soil close to the surface, while buckwheat scavenges phosphate.”

For Duncan Ellis, however, it’s a flexible, low cost approach to establishing an OSR crop. “Apart from the seed, we won’t spend a penny on the crop before Christmas – the mix of plant species hopefully should confuse pests and reduce disease pressure. Then we’ll look at what we have. Those areas with a decent OSR crop we’ll spray off with Astrokerb (aminopyralid+ propyzamide). Where there’s not such a strong crop, the cover will be followed with spring barley or beans.”

Livestock is overlaid within the arable rotation, continues Richard. “What we’re looking to do is improve the land-use equivalence ratio. We hope to carry out a trial grazing of a well-established cereal crop in the early spring, potentially omitting a T0 fungicide spray. The aim is to take inspiration from Nature and increasingly replace the pesticide armoury with a bank of plant species.”

Church Farm spring beans: how the finances stack up

Farm facts

Church Farm, Litlington, E Sussex

- Farmed area: 728ha arable; 600ha grassland

- Cropping: Winter wheat; Winter oilseed rape; spring barley; spring beans; temporary grass leys and permanent pasture

- Livestock: 40-head beef cattle; 1200 breeding ewes; 200 Herdwicks

- Soil: Varies from alluvial clay to flint/chalk downland

- Mainline tractors: Challenger 765C; Massey Ferguson 7630; MF 6480

- Combine: New Holland CR9080 with 9m header

- Drill: 6m Horsch Sprinter

- Sprayer: Househam with 3000-litre tank and 24m boom

- Fertiliser spreader: Kuhn Axis 40.1

- Loader: JCB TM130S

- Cultivation: 6.5m Väderstad Carrier; 12.5m Twose rolls

- Staff: Two arable, two livestock, one part-time; 15 in the brewery

Pulse quickens in an unusual global market

To describe the pulse market as “quite interesting” could be the understatement of this very unusual season, says PGRO chief executive Roger Vickers.

“The good news is that, despite uncertain volumes and high prices, the market for feed likes pulses and is keen to source non-soya protein.”

Internationally, the market for vegetable protein is growing and pulses are key to supplying that demand. “Whether peas or beans they are being snapped up, and a preference for local production and consumption also appears to be gaining traction, especially in Europe,” he adds.

The trade shenanigans taking place between the USA and the Chinese seem to be having an effect, notes Roger, with the Chinese busy buying up Canadian peas, making up for the loss in Canadian exports to India as their effective embargo continues.

Here in the UK, Franek Smith of Pulses UK reports that seed availability for the 2019 bean crop is a significant topic of conversation. “Winter beans received a derogation for quality, and the same is likely to be requested for spring-sown stocks, which appear to be slightly but not significantly better.”

The demand for winter beans has been high. An open autumn period and good seedbed conditions has tempted some to sow spring beans in the winter. Others are looking closely at failing oilseed rape crops with a view to replacement with pulses in the spring, he notes.

With the UK feed bean crop significantly down, ex-farm prices are holding strong at 220/t, but Franek believes this is likely to be short-lived. The feed bean market for 2019 crop has already opened with some merchants and it is possible to receive offers of circa £20/t ex-farm over Nov wheat futures, he adds.

Allowances for up to 20% Bruchid damage have been accepted for human consumption beans, although he thinks it’s unlikely that the UK will export as much as 100,000t from crop 2018 to this market. Value for exceptional quality samples with less than 5% bruchid damage have hit as high £300/t ex-farm with a more normal premium at around £50/t ex-farm over feed values.

- The PGRO 2019 Recommended Lists have now been published – a full report can be found within the Pulse Magazine, included with this issue of CPM.