With serious question marks hanging over the future use of diquat, alternative methods of potato haulm destruction are still firmly on the agenda for most UK potato growers. CPM looks at two different approaches.

The future for potato production may eventually be a move back to a more holistic crop management process.

By Lucy de la Pasture and Rob Jones

At the time of writing, the European Commision has not been able to decide on renewed authorization of diquat. At the last meeting of the Standing Committee on Plants, Animals, Food and Animal Feed (Scopaff), the EC put the proposal to the vote to no longer allow diquat use. But there was no required majority for the proposal, nor a required majority against renewed admission.

With flail and spray there’s always the risk of flailed stems and canopy lying across the newly flailed crop, particularly in wet weather.

What will happen next isn’t entirely clear, but the EC can put the proposal to the appeal committee and if the voting ratio is the same, they can impose the prohibition. The EC can also make a new proposal. In the meantime, diquat remains available but many agronomists and producers are experimenting with other desiccation methods, just in case.

County Crops agronomist Tom Smith advises on 400ha of potatoes in West Lancs and the Yorks Wolds. He believes diquat’s effectiveness has set up a culture where growers and advisers barely have to give desiccation a second thought, but its potential loss would prove a significant game changer for the industry.

Losing active ingredients is a problem the potato industry is getting used to adapting to. “In recent years we’ve seen the loss of key products such as sulphuric acid, paraquat and most recently linuron. Diquat has been under regulatory pressure for over two years now so it’s given me a useful opportunity to work with growers on effective alternatives,” says Tom.

“Perhaps the future for potato production may eventually be a move back to a more holistic crop management process, rather than separating the agronomy into a sequence of events – pre-emergence, post-emergence, blight control and desiccation – all heavily reliant on fast-acting chemicals,” suggests Tom.

“Successful desiccation is a critical phase in the growing season, enabling growers to stop growth of the canopy when tubers reach the optimum marketable size. It also helps to reduce the risk of tuber blight, blackleg and other diseases before the potatoes go into store” he adds.

Although ‘flail and spray’ seems to have become the go-to alternative to diquat, Tom points out that it does have drawbacks, particularly in regions like his which often experience more than their fair share of rain.

“With flail and spray there’s always the risk of flailed stems and canopy lying across the newly flailed crop, particularly in wet weather. Poor weather, combined with a lack of investment in a good flail machine, can hinder the effectiveness of alternative desiccants that rely on contact activity with exposed stems,” he says.

In dry weather Tom recommends using Gozai (pyraflufen) at a rate of 0.8 l/ha for stem desiccation as part of a flail and spray approach. But it’s not just the choice of desiccant that makes the process successful, believes Tom, canopy management has a big part to play too and that means planning for desiccation right at the start of the season.

Tom advises managing and manipulating the size of the crop canopy using controlled-release fertilisers, with the ultimate goal of potentially reducing nitrogen rates to create more stable canopy growth. He believes this approach is suited to growers who want to flail and spray more efficiently, or growers who are averse to flailing and are considering other options without diquat, such as sequencing contact herbicides in a longer desiccation process.

“Use of controlled release fertiliser still gives growers the yields, but the crop canopy is less dense due to the more gradual release of nitrogen. The added benefit to this approach is that you’re able to select a desired release period for the nitrogen, which is influenced by the polymer-coating used. This adaptability makes it a useful canopy management tool for many different varieties and soil types.

“Over the past two years I’ve used a polymer-coated fertiliser called Promax at rates of 150-170kgN/ha on varieties such as Harmony, Estima and Sagitta. All the crops have yielded well, even at the reduced rate,” he says.

“Looking beyond the cost savings from reduced nitrogen application to the crop, canopy growth is also far more controlled, making it easier to manage at desiccation” he adds.

Tom is keen to stress that his research is still at an early stage and more trials will be required to gain a greater understanding of what is and what isn’t possible.

“With the potential loss of diquat, it’s vital for both agronomist and grower to plan ahead for desiccation with a constant evaluation of tuber size, weather forecasts and disease pressure. For those growers and advisers who are currently trialling sequences of Gozai and Spotlight Plus (carfentrazone) as an alternative to diquat or flail and spray, the use of controlled-release fertilisers could be a positive step forward in helping them to achieve better results.”

Lincs grower, Wayne Dye, says for him consistency and speed of action are all-important factors for when it comes to haulm desiccation. The amount of canopy on his crops means that it’s not just product choice that’s critical, but how it’s applied and attention to detail.

On his farm near Spalding, Wayne grows the variety Markies, destined for the chip trade. Maintaining tuber quality and consistency of product are obviously high on the list when it comes to maximising marketable yield, but with that particular variety comes another challenge that requires careful management, he says.

Wayne’s medium silt soils are ideal for growing high yielding potato crops in very drought-tolerant conditions. But with an exceptionally late-maturing variety like Markies, the amount of haulm generated can be colossal. With thick stems, an efficient burn-down that will keep the crop disease-free and maintain tuber quality for consistent fry colour is critical. He finds using Spotlight Plus within his desiccation programme is an essential part of that management, particularly because it has a seven-day harvest interval.

“The variety produces such vast amounts of haulm that ensuring an even and penetrating application of desiccant is paramount,” he explains. “We generally make two applications, firstly with a diquat-based product at the first sign of senescence. Once enough leaf has been removed, then a second application of Spotlight at 1.0 l/ha is made, which hopefully finishes off the stems.

“We’ve experimented sequencing the two desiccants the other way around, using Spotlight Plus followed by the diquat, but that wasn’t nearly as effective. It’s all about a progressive take-down of the canopy and that has to occur as soon as the crop shows the first signs of senescence. The programme has to be quick-acting and capable of doing the job required,” he comments.

With such a dense canopy, water volume is also critical, points out Wayne. He always applies the product in at least 400 l/ha (the minimum volume being 300 l/ha). “We’re looking for large tubers with Markies, ideally with a bag count of 100 or less. To achieve this the crop requires a long season of growth, although the tubers initiate early enough, the maturity is late,” he explains.

Wayne usually manages to complete the desiccation process with two applications, but in 2017 three were needed (an additional 0.6 l/ha Spotlight Plus being applied seven days after the first) as prolonged wet weather meant that the growing season was more protracted, and the haulm volume was significantly greater.

“During the first application we had the booms of our self-propelled Sands SLL4000 up as high as they’d go. The height of the crop was unbelievable, and we needed the three applications to do the job.”

Soil type biggest influence on greening

Where irrigation hasn’t been an option this summer, tuber greening may well prove a problem on heavier soil types. Late planting this spring may have meant seed wasn’t planted deep on soils prone to cracking because a further delay in emergence was the last thing growers wanted.

On average 5% of yield is affected by greening in most seasons, but in severe cases as much as 20% of yield can be lost due to outgrades. Tubers turn green when they are exposed to light, causing the production of chlorophyll and glycoalkaloids. While chlorophyll is tasteless and harmless, glycoalkaloids are bitter-tasting and can occur at potentially toxic concentrations in green tubers, consequently packers have very low thresholds for greens in contrast to tuber blemishing diseases.

A research project, carried out at NIAB-CUF, has been investigating the factors that may contribute to greening. These included tuber formation, stolon architecture and nitrogen rates, but it was concluded that none of these was as important as the amount and type of soil that sits above the potatoes as they grow, says Dr Simon Smart, research associate at NIAB-CUF.

“Factors known to influence tuber greening include row width, planting depth, ridge shape, soil cracking and variety. Differences between varieties are considered anecdotally to be caused by differences in stolon length and stolon depth between varieties – if tubers develop on stolons close to the surface or on long stolons, they should be more likely to turn green.”

Stolon length is known to vary between varieties but the influence of this on the position of tubers in the ridge and their susceptibility to tuber greening had not been investigated before. A fellowship from AHDB and additional support from Cambridge University Potato Growers Research Association (CUPGRA) provided an opportunity to investigate the physiological and agronomic causes of tuber greening over three years.

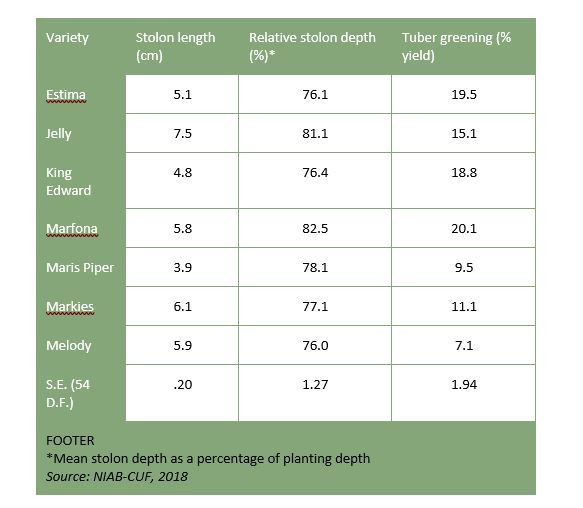

Seven varieties (Estima, Jelly, King Edward, Marfona, Maris Piper, Markies and Melody) were grown in a replicated experiment to investigate the relationship between stolon architecture and tuber greening. Plots were sampled around the time of tuber initiation and the length and depth of every stolon was measured. In the middle of the season, stolon length and depth, and the position of each tuber were measured by painstakingly removing soil from around each plant – a process similar to an archaeological dig. Samples were also taken after desiccation to assess for tuber greening.

In addition to the replicated trial, 36 commercial crops were surveyed to quantify stolon architecture and to relate the position of tubers in the ridge to tuber greening. Both within and between years, differences in stolon architecture between varieties didn’t account for differences in tuber greening.

“This was probably due to tuber depth not being directly related to stolon depth because of differences in tuber size. In commercial crops, planting depth varied widely both between and within crops,” explains Simon.

Average stolon length and depth and tuber greening over three years of the variety experiment

The work showed that planting depth and soil type are two of the most significant factors when it comes to in-field tuber greening. Soil cracking was found to be a significant factor, so clay-based soils require more soil above the tubers to prevent greening.

Crops grown on soils with a high clay content and planted shallowly are particularly at risk from tuber greening, especially when yields are high and tubers are large. The optimum planting depth to limit tuber greening may be deeper on soils with a higher clay content but may reduce overall yield.

“On sandy and peat soils, few green tubers were found with more than 2.5cm soil coverage, but on clayey soils, green tubers were found with more than 5cm of soil coverage. Tuber greening was most severe on sites where more tubers were close to the soil surface and where the clay content of soil was higher.

“Unfortunately, planting deeper is known to delay emergence and therefore reduce yield, so growers must find the balance between achieving a high yield while also minimising tuber greening. Where tuber greening is substantial, it’s advisable to investigate where the green tubers are in the ridge. Check to see if they’re exposed at the surface, growing out of the flanks or unexposed and this will aid any decisions to adjust planting depth and ridge geometry in the future.”