One of the first farmers to join YEN, Mark Means is running a number of on-farm trials focused on building a resilient crop that enhances yield at the end of the season. CPM visits to discuss this new approach.

The trials are a step on and ask the next questions.

By Tom Allen-Stevens

Several dozen spray containers have been arranged neatly into groups and marked up as ‘jobs’. It’s a sign that, like everything else at The Laurels on Terrington Marsh in Norfolk, the spray season’s keen to get underway. Wheats are waking up as warmth gradually builds in the sodden Fen soils, although they still sit dank and heavy after the long, wet winter.

The late start to spring has meant a few last-minute changes to the T0 battle lines – Mark Means adjusts the recommendation sheets and puts an extra litre of Tempo (trinexapac-ethyl) into every job group. “One thing I’m really conscious of is lodging,” he says.

Conscious that lodging may be a problem in a late spring, Mark Means has applied

“We haven’t had the root growth we’d usually expect over the winter, and there’s probably been a bit of root-pruning as a result of these water-logged soils. As top growth gets underway, I’m concerned crops won’t have the anchorage to cope and we’ll see some of the wheats go over.”

A total of 480ha of winter wheat sits in the Grade 1 and 2 silt to silty clay, moisture-retentive soils. With around 760ha of cropped land, potatoes are grown one year in eight, with sugar beet, onions and vining peas alternating with the wheat crop. Yields average 10.8t/ha (11.2t/ha excluding 2012) and these receive a fair amount of scrutiny – Mark was one of the first farmers to join the Yield Enhancement Network (YEN) and achieved the highest yield in its first year.

Six years on and, aside from his YEN crop, he’s involved and takes an avid interest in three on-farm trials looking to test different nutrient regimes, SDHI timings and the role of biostimulants. “YEN’s a competition, and it’s about learning from others’ mistakes and them gleaning lessons from yours. But it’s also about a scientifically robust, economically sound approach to growing wheat.

“For me the trials are a step on and ask the next questions – what is the appropriate dose to control septoria? What role do amino acids play? And how can we use nutrients to manipulate crop growth?”.

There’s probably been a bit of root-pruning as a result of the water-logged Fenland soils.

So while the T0 preparations are finely tuned to ensure a crop that’s not only well protected from disease but stays standing, Mark is already focusing how to manipulate crop growth at the end of the season. The moisture-retentive soils and climate of the farm’s location bring him some aspects he’s keen to optimise.

“The sea frets we get – mists that come off the Wash – mean we can keep wheats going for longer. So we aim to give them a cool running engine. Provided temperatures don’t get too hot during summer and we get the sunlight, there’s plenty of potential to really explore what we can do towards the end of the growing season.”

And that’s the focus of the fungicide trial. He’s been involved in on-farm trials for a number of years – as a member of Bayer’s Xpro Farmers Club, he’s done some Judge for Yourself trials, that put the company’s SDHI chemistry through its paces. “Normally yellow rust is our main priority disease-wise, but we’ve been growing varieties recently that are quite susceptible to septoria. The tramline trials have been useful to illustrate the difference the SDHI chemistry makes,” says Mark.

But now he’s looking to take advantage of the chemistry’s greening ability. Ascra (bixafen+ fluopyram+ prothioconazole) has a label claim for the physiological benefits it brings the crop. What’s more, Bayer claims growers receive a consistent 0.3t/ha yield benefit from using Aviator (bixafen+ prothioconazole) and Ascra, even in a low disease year.

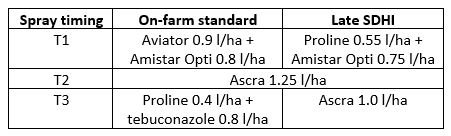

Going for green: the SDHI programmes on trial

Variety: KWS Barrel; Both areas received a T0 application of Cherokee 1 l/ha; Amistar Opti – azoxystrobin+ CTL; Proline – prothioconazole.

“Research suggests that for every day I can extend green leaf area (GLA), the crop puts on an extra 0.15t/ha,” reasons Mark. “When Aviator first came out I tried it at T2 and T3, and, although I was running no comparison, it did appear to extend the GLA. So the trial is going to look a bit more closely at putting the SDHIs in the T2 and T3 slots.”

But isn’t it a lack of SDHI at T1 going to leave his crop exposed? “The focus of my fungicide programme is to keep disease out of the crop. Chlorothalonil is still a very effective protectant fungicide, and NIAB trials data show you can even remove the azole from a programme and retain the yield. Of course, you wouldn’t do that in practice, but as long as you keep the crop in a protectant situation, you don’t need an SDHI at T1,” he says.

This comes down largely to timings, he notes. “We aim to get the T0 on when leaf four has emerged on the main tiller. We usually go with CTL plus a cheaper triazole such as Cherokee (CTL+ cyproconazole+ propiconazole). The timing needs to be spot on at T1, with leaf three fully emerged on the main tiller.

“We’d then go with a T1.5 application, when leaf two is three quarters to fully emerged. It’s a great timing for Terpal, so we’re going through the crop anyway, and it’s an opportunity to add more CTL and perhaps a strob.”

With the T2 applied at flag leaf fully emerged, the quandary then is what to about the timing of the T3. “The T2 and T3 timings are the most important ones for fusarium control. The timing of the T3 is critical in a bad fusarium year – as soon as the first anther comes out is when you should apply, which comes fairly close after the T2. But if it’s doing more of a disease top-up, it wants to be extended to a little later,” says Mark.

As far as chemistry is concerned, the prothioconazole will be doing the job on fusarium, so the addition of a late SDHI won’t make any difference, he notes. Its main purpose will be to prolong GLA.

But that potentially brings another quandary: “What do I do if the grain is ripe but the crop’s still green? It could stall the combine. The other worry is that we might get a year like 2012, when late-maturing varieties were still green, but there’s no sunlight to fill the ear.”

These quandaries are among some of the unknowns he’s hoping the trial will address. But he’s confident this shift in emphasis on using SDHIs to boost crop performance rather than simply protect against disease, is part of a picture that will see his crop perform closer to its YEN potential of around 20t/ha.

“As septoria gets harder to control, I don’t believe the answer is to throw more fungicide at it. It’s first and foremost about keeping the crop in a protectant state, and not allowing disease in. But it’s also about building a crop that’s inherently healthy – that’s where manipulating nutrients and the use of amino acids can help. A healthy crop is also more likely to reach its potential.

“It’s also important that we can measure the results of any trials we do, so we can learn the lessons and have a quantifiable result that provides a sound basis for a business decision. With the single farm payment dropping away, we have to be sure of every expenditure we make on our crops.”

Standing ability ranks high in variety choices

A member of local grain co-operative Fengrain, Mark Means aims to grow for premium local markets. His farm hosts AHDB Recommended List trials, and this informs his choice of varieties, although with Cordiale, Gallant, KWS Barrel and KWS Zyatt making up his portfolio, he professes he doesn’t hunger for new genetics.

“The wheats are fully market-orientated, and also perform an agronomic role. People tell me off for growing Cordiale but it’s a steady performer – early to harvest from late drilling – and has yielded up to 13-14t/ha. Gallant again is early to harvest, but it’s also grown for its consistency of protein and Hagberg. We are looking to replace it, however.”

The jury’s still out on the two relative newcomers. “We’ve had two years of growing Zyatt for pre-basic seed and it’s done well, with a similar standing ability as Cordiale. Barrel is interesting because it’s a high-yielding Group 3 biscuit variety. It does require management, but then we’ve a very good spray capacity and apply a five-spray fungicide programme. I like the look of Elicit for 2019 – it has reasonable standing ability and good disease resistance so may be a replacement for Gallant.”

Standing ability is a key trait Mark looks for, and this scored against KWS Siskin that was grown last year. “We have a very good PGR armoury to control lodging and put on three applications of trinexapac-ethyl and two of Terpal (mepiquat chloride+ 2-chloroethylphosphonic acid), but still Siskin was a problem.”

The dry weather during April last year meant the crop took N up quickly during May, he explains. “It was like a smouldering bonfire – the wind changes direction and woompf – away it goes.

“Managing Siskin through that burst of growth is a bit like driving a fast car and someone takes the steering wheel away. I like to be in control of my wheats but with Siskin you feel like you’re fighting against nature. It’s probably better suited to less fertile soils,” concludes Mark.

Trials made to think about building more sink

An N-Sensor lies at the heart of Mark Means’ nitrogen applications – early liquid doses geared around evening the crop up are switched to solids later in the year, with rate varied to match crop potential.

In late spring, the crop receives 100kg/ha of potash, applied as Korn Kali (40% K2O, 6% MgO, 4% Na2O and 12.5% SO3). “This brings the magnesium and sulphur to the crop along with the potash, and it spreads well to 36m through our Amazone ZAM Hydro spreader,” says Mark.

The nutrient trials, run with Yara, look to take this practice a step further. “It’s a crop of Cordiale after a double vegetable crop, so the site is very fertile. We’re looking closely at leaf analysis, and will tweak trace elements and limits, particularly at the T2 and T3 timings, to see if we can improve the fecundity of grain sites the crop produces.”

The theory on test is whether you can manipulate the sink capacity of the crop, explains Mark. “When the crop’s setting its number of grain sites, we want to trick it into believing there’s enough source available to produce more sink.”

This will be achieved by making sure there’s a generous supply of all macro and micronutrients, particularly towards the end of the season as the crop looks to build grain sites. The inherent fertility helps, and the wheat’s only received one N application so far – 60kgN/ha in early April. The PGR programme will keep it in control and the plan is to load up the crop at flag leaf.

“We’re also paying close attention to nutrient levels, using a SPAD meter and taking tissue samples to identify the crop’s requirements. One surprising aspect is that boron has shown up as a deficiency for the past 2-3 years, so we’re applying 200-250g/ha,” says Mark.