Farmers have had the opportunity to scrutinise Defra’s flagship Environmental Land Management Scheme as plans and proposals begin to come together. CPM joins the discussions.

Farmers are not currently adequately rewarded for the contribution they make, but are best placed to decide how to provide public goods.

By Tom Allen-Stevens and Rob Jones

A scheme that will build back greener, reward farmers for the true environmental good they do, one that’s farmer-led and flexible in its approach. Sounds too good to be true?

Scratch beneath the glossy veneer of Government plans for the new Environmental Land Management (ELM) Scheme and there’s a heap of unanswered questions and reservations. Nevertheless, this will become the main public funding delivery mechanism for farmers across the UK, and England in particular, as the transition from the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) gets underway.

Whether it will complement or replace farming and food production is one of the fundamental questions, along with just how much you’ll be paid, and how this will be decided. Where you’ll go for advice and how you’ll be inspected and monitored are also key concerns.

“This Government’s pledge is not only to stem the tide of loss [in our natural environment], but to turn it around – to leave the environment in a better state than we found it,” stated Defra secretary of state George Eustice, setting out his vision for a green recovery last month. “We need policies that will not only protect but that will build back – with more diverse habitats that lead to a greater abundance of those species currently in decline.”

The £3bn budget currently spent on agriculture across the UK (£2bn for England) is a “game-changing” opportunity to do just that, he said. “ELM will put around 10-15 times more public funds into environmental projects than we’ve ever seen before. Biodiversity and water quality are moving in the right direction and the rest of the world will be coming to the UK to see how it’s done.”

So just how will it be done? A series of policy discussion webinars has shed light on current plans. The ELM Scheme is set to be launched in 2024, with a National Pilot due to start next year. It will build as BPS payments are phased out from 2021-27 and will take over from Countryside Stewardship as the main form of rural funding for farmers and land managers.

The aim is to pay public money for the provision of public goods, moving away from the current system of direct, area-based payments, explains deputy director for ELM National Pilot, Test and Trials, advice and technical guidance Gavin Ross. “Farmers are not currently adequately rewarded for the contribution they make, but are best placed to decide how to provide public goods.”

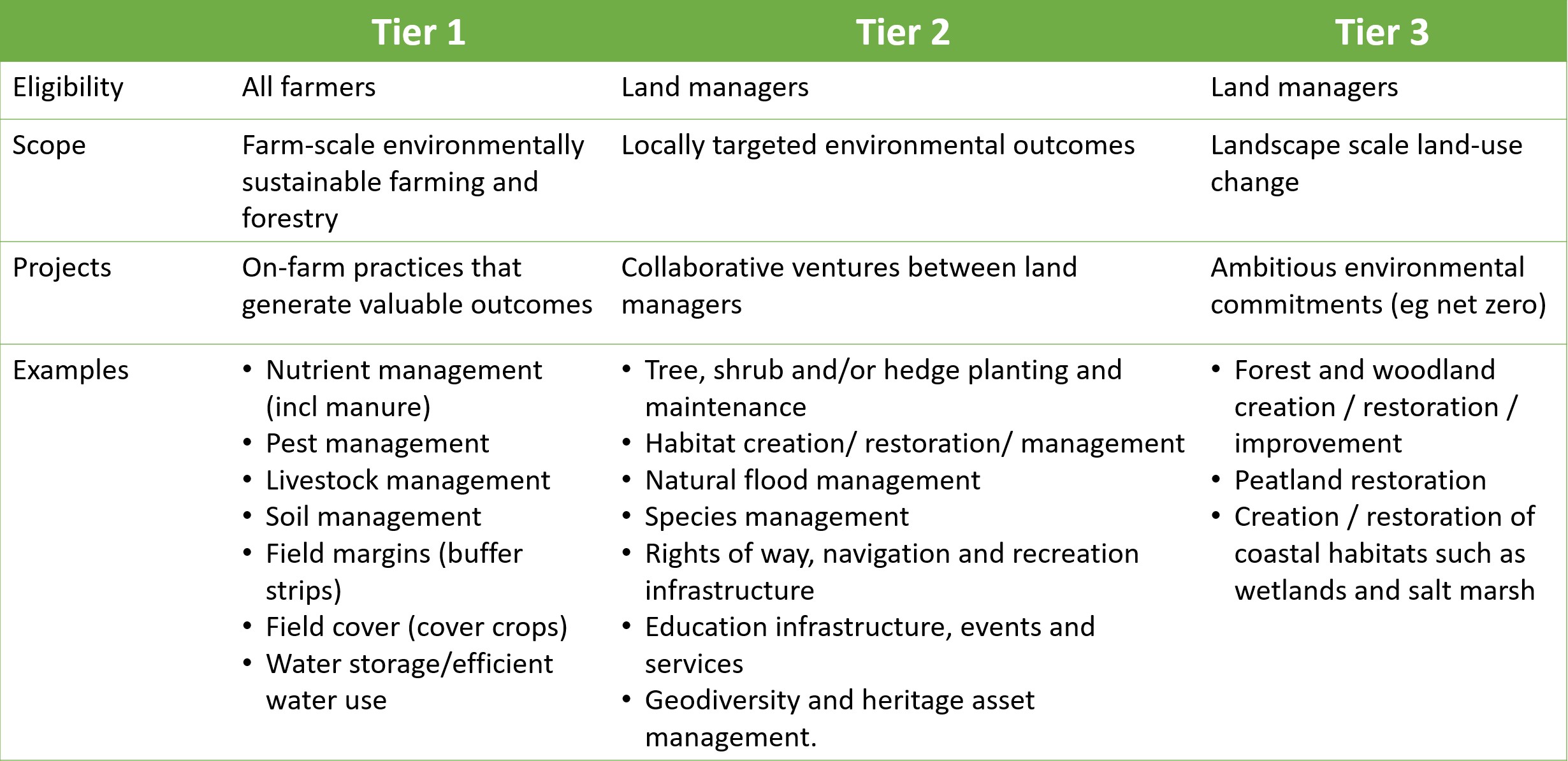

The priorities here are: clean and plentiful water; clean air; protection from and mitigation of environmental hazards; mitigation of and adaptation to climate change; thriving plants and wildlife; beauty, heritage and engagement. The plan is to deliver these through three tiers.

There are a number of key areas in which the ELM Scheme will be better than current agri-environment schemes, says Gavin. “They’ll be less prescriptive and bureaucratic – we’re aiming for a lighter-touch approach. We want to give land managers more flexibility to create their own land management plans, both at a farm-scale and across a local area. And we want it to deliver the 25-year Environment Plan and achieve net zero by 2050.”

Exactly what the ELM Scheme will pay for still hasn’t been decided. “We’re compiling a long list and are gradually refining this,” he notes. Feeding into this are the Tests and Trials currently underway that are taking forward 62 proposals, two of which have already completed. These pave the way to the National Pilot that starts next year.

“We want to test three main aspects: how best to construct different types of ELM agreement at different scales; how to target ELM incentives to deliver specific environmental outcomes in specific areas; and the underlying scheme mechanics,” says Gavin.

The ELM Scheme won’t be the only support available – there’ll be animal welfare grants, investment support and funding for farm-based R&D projects.

The NFU has some key concerns, however. “ELM should have farming and food production at its core,” states NFU vice president Tom Bradshaw. “The best delivery of environmental services is where these go hand-in-hand with farming and shouldn’t favour land-use change. We need to know the money will still be coming to farmers and have concerns over reference to land managers – this is not about funding for country parks and urban spaces.

“We’re also nervous that it won’t reward farmers for those assets already on farm. There’s a danger the baseline creeps up – arable farmers have already lost the option under Countryside Stewardship to be paid for field corners to be taken out of production, for example.

“But most of all, Defra has to make this attractive to farmers. It must reward above just income forgone and take into account the considerable management time farmers invest. To excite farmers they should be able to profit from delivering for the environment, but it must also withstand the scrutiny of a Treasury spending review, and that’s a challenge.”

This last point is a key consideration – Defra wants a high uptake of the ELM Scheme from farmers and land managers, while there are currently 85,000 BPS recipients. There’s also the barrier of bureaucracy, the sense of dread at petty penalties and the need for clarity on exactly what scheme requirements will entail. Queries have revolved around some key areas.

Payments

“Getting this right will be critical,” notes Gavin. “It needs to be financially attractive for farmers but deliver value for money for the taxpayer – we’ll be doing a fair amount of testing on payment rates during the pilot.”

Initially it’s envisaged farmers will be paid for the work they carry out, but Defra is investigating a system of payment by results. “We don’t want this to be complex, although we understand delivery of environmental benefits is not a simple measure.”

The scheme is also designed to be stackable and build in elements not specifically funded by Defra. So a farmer might start off with a Tier 1 scheme on their farm, then join a collaborative scheme in Tier 2 with other farmers in the local catchment, part-funded by a water company, then join a carbon-offsetting Tier 3 venture, set up as a national scheme.

Maintaining existing environmental assets will be included, says Gavin. “It’s essential we look to pay where there’s a benefit, whether that’s already in place or not. But there’s an expectation that farmers should pay to comply with legislation, so the ELM Scheme shouldn’t fund slurry storage, for example.”

Trusted advisors

Defra is keen that farmers can access professional advice to address queries when applying and also to facilitate and co-ordinate Tier 2 and 3 schemes. Their role may also involve a level of monitoring and assuring compliance. “These people must have the relevant skills and knowledge, but must be trusted, give consistent advice, be credible and cost effective. An important aspect is that farmers should be able to choose who they deal with,” says Gavin.

Defra’s looking at a number of options, he adds, including an accreditation scheme, but it’s likely to involve existing advisors whom farmers already work with, such as an agronomist, rather than introducing a new band of professionals.

Inspections

Expect to see a move away from the prescriptive, bureaucratic approach. “We think there’ll be a role for self-assessment, and record keeping will remain a key part of monitoring, especially keeping photos,” says Gavin.

“But we want a proportionate approach, with the emphasis on assistance and guidance to improve a plan, rather than imposing penalties. We’re keen to support farmers into the scheme and ensure everyone understands its aims. So rather than penalise someone for not delivering, we’d encourage them to be less ambitious – that’s a seed change from current schemes.”

The deadline for submitting a response to the policy discussion was 31 July, with an update expected later this year.

Don’t ‘dumb down’ ELM

Marek Nowakowski

The ELM Scheme is in danger of achieving little in the way of lasting wildlife benefits, warns farmed wildlife specialist, Marek Nowakowski.

He’s worked with growers for almost 40 years to bring increases in farmland wildlife within profitable, modern farming systems and has been involved in scientific studies with the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (CEH) and others that have helped shape environmental policy.

“2024 will be here in no time and there’s huge political pressure to do things as broadly as possible. This means Tier 1 of the ELM Scheme, in particular, is in serious danger of being dumbed down so it turns out to be no better than former schemes in actually increasing farmland wildlife. We must not let this happen.”

Studies such as the CEH-run Hillesden experiment, for instance, have shown a more targeted approach delivers significant increases in a whole range of environmental indicators, he says, including wildflower, invertebrate and pollinator populations and winter seed provision for birds.

Marek underlines the importance of both vegetation succession and heterogeneity for the best results. With natural vegetation succession, habitats are managed so the aggressiveness of annual weeds under the relatively high fertility conditions of most arable land doesn’t result in poor habitats for wildlife and being overcome by weeds.

Equally, the different needs of insects and birds mean that sufficient heterogeneity is vital if habitats are to be the most productive and stable in providing wildlife homes as well as food sources and mating opportunities.

Marek has a number of tips for the successful creation of wildlife habitats:

- Wildflowers thrive better and support much more insect life on the warmest, south-facing sites.

- Put tussocky grasses on the coolest north-facing field edges to provide insect hibernation sites.

- Longer-lived wildflower and tussocky grass margins are important alongside watercourses and across slopes vulnerable to erosion

- Annual and other short-lived mixtures are best located elsewhere for the greatest soil and water protection.

- Broadcasting wildflower seed onto a fine firm seedbed followed by ring-rolling is the best approach rather than drilling.

- Regular cutting in the first year and occasionally thereafter is vital to restrict annual weeds and encourage the most resilient and diverse perennial swards.

- Create a range of different habitats, ensuring the right distance between them, and cut them at different times of the year to ensure continuity of resources.

- Appropriate management of hedgerows and uncultivated ground will help fill the early spring ‘hungry gap’, as will supplementary bird feeding.

- To maintain the greatest habitat diversity, manage hedges to different heights, keeping those running north-south taller than those running east-west.

- Manage quality habitats like a crop and get their agronomy right