Understanding the world beneath our feet holds the key to developing sustainable farming practices. CPM looks at the progress being made in the AHDB-BBRO Soil Biology and Soil Health Partnership.

Soil is like a desert with the occasional oasis.

By Lucy de la Pasture

The importance of the soil in sustaining life has been recognised for centuries. In the 1500’s Leonardo Da Vinci famously said, ‘We know more about the movement of celestial bodies than about the soil underfoot.’

Since then a massive amount of research has taken place into soils but a disconnect remains between pure science and its application in the field, says Dr Elizabeth Stockdale, NIAB head of farming systems research. She’s leading the Soil Biology and Soil Health Partnership, part of AHDB’s GREATsoils programme, and has a remit to address this disconnect and find practical ways of assessing soil health.

It’s a project that has a dynamic approach, working closely with industry partners as well as growers, who are sharing their tacit knowledge of managing their own soils and providing a testbed for a package of indicators for soil health.

“The partnership brings together expertise spanning from the newest science to practical knowledge. Within the project, the theory generated needs to be challenged by practice and change in response to the questions and demands of the real world,” she says.

AHDB’s Dr Amanda Bennett adds that by bringing together researchers and industry, existing knowledge can be built on and consolidated to give a better understanding of soils and the effect different management practices have on them.

“The early part of the project has concentrated on establishing what is already known and there’s been a series of open meetings and workshops to update growers,” she explains.

This has involved a huge literature review, which hasn’t generated any headlines but has consolidated the knowledge underpinning research methodologies, explains Elizabeth. “The second step has hunted for hidden information on soil biology and health and this has resulted in updates to predictive soil models and has given an insight into a methodology for measuring soil health.

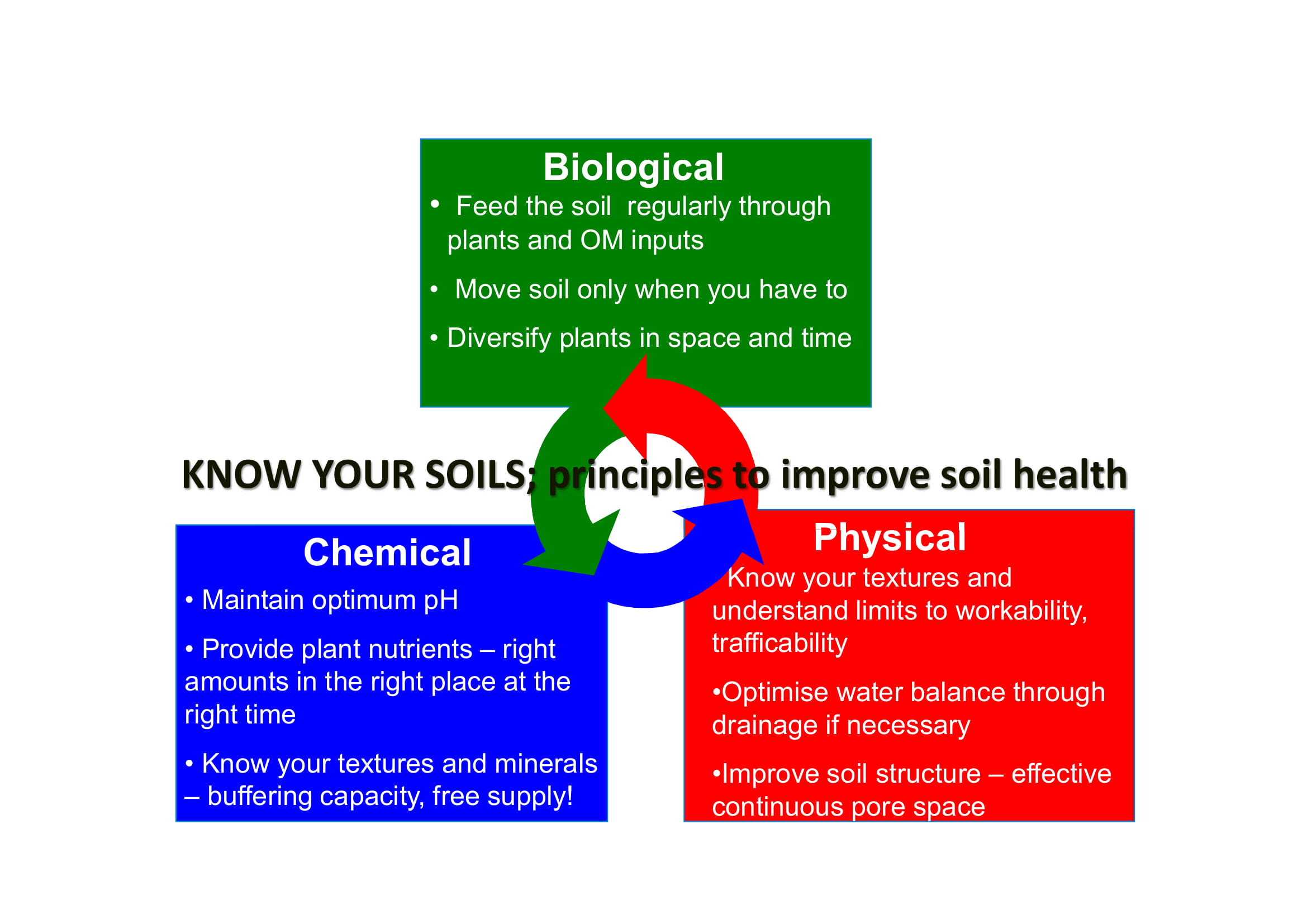

“Soil health is a complex issue which has to take into account the interactions of physical, chemical and biological factors and overlying all of these is the influence of different grower management systems. We’re trying to find a useful measurement of a soil’s health that doesn’t oversimplify these factors and is able to produce useful guidelines,” says Elizabeth.

And this is where innovative farmers are helping to shape the project. “Many growers are already ahead of the curve and have worked out management practices that work on their soils. They’re looking at the impacts on their soil biology, typically by measuring earthworm numbers, and how this affects trafficability. Through these observations they’re in a good position to challenge researchers.”

The willingness of growers to engage, share information and best practices was evident in the recent round of open meetings and workshops, she adds.

Soil biology is the area where the least is known in a practical sense, comments Amanda. “Within the literature review there were over 40,000 references to soil health but little information that could be easily translated into management practice.”

Elizabeth agrees that soil physics and chemistry are much better understood. “All the processes that take place within the soil have been considered as if they were just a chemical reaction, forgetting about the soil organisms that actually facilitate them. The calculation of nitrogen fertiliser-use efficiency is an example, where efficiency depends on ammonium being converted into nitrate as part of the nitrogen cycle. The bacteria that actually make that conversion happen for their own energy supply aren’t considered.

“If you can’t see something, it’s much trickier to measure. Soil is like a desert with the occasional oasis, there are large areas with nothing on and small areas with a large amount of biological activity. That makes soil sampling to assess soil biology a hit and miss affair,” she says.

Because of the structure of its environment, soil life isn’t very mobile. A large proportion lies dormant, waiting for the right opportunity to come along before bursting back into life. “It adds to the complexity of studying soils, but from a management point of view it means soils are very resilient.”

In recent years, molecular tools have emerged which can measure the DNA of organisms in the soil, making the study of biological life possible. “This means we’re gaining a better understanding of the interactions within the soil food web and decomposition.

“Decomposition is a really important process within the soil food web, transforming the sun’s energy into food for soil biology. The gums and glycoproteins produced in decomposition help to stick soil particles together, so soil structure is also about biological processes as well as physical ones. Biology becomes the linchpin of soil health,” she says.

Although it’s easy to see the value of good soil health, it’s much more difficult to work out how to harness it and change management practices to improve its status. “We’ve become input junkies because we’ve discovered how to use these well to increase productivity. The trouble is this has allowed us to ignore the importance of soil biology and the inputs approach has created a less resilient system.”

Review of the large number of experiments that have been carried out, including long-term experiments at Rothamsted Research, have produced some good principles to help improve soil health, highlights Elizabeth.

“They’re not rocket science but what’s important is to recognise the soil’s physical, chemical and biological interactions are a system. If one thing is wrong, then the whole system becomes out of balance. A healthy soil maintains balance and is able to support good production and deliver ecosystem services.

“If the physical and chemical properties of the soil are right, the chances are its biology will be in the right space to respond as needed. If you build it, they will come,” she says.

The big question is how to take these basic principles and develop into local practices. This is something the Soil Health and Soil Biology Partnership is working on, explains Elizabeth.

“Research is being carried out on long-term trial sites across the UK, looking at how different management strategies influence the soil biology and assessing the best ways to measure this. Farmer groups are also working in tandem with these trials to try out different ways of measuring soil health,” she says.

“The physics, chemistry and biology of the soil need to be linked together and this means looking at soil in a slightly different way. Standard soil tests look at chemistry, we can add a biological measurement, but these still don’t tell us anything about the soil physics,” she says.

“The new test will need to fit into routine farm practice and help to identify areas that may need further investigation, a bit like a routine health check at the GP’s clinic which may highlight a possible problem needing further tests to identify the cause.

“The farmer groups are testing a scorecard for soil health and it uses a traffic light system. As the measures being tested become more robust, DNA testing will be introduced to help identify the soil biology that respond to changes in management practices, so could be used as useful indicators,” she explains.

Amanda believes the development of an industry standard toolkit to measure soil health will greatly enhance the grower’s ability to better understand and manage their soils. “Ultimately this work will help produce effective and resilient farming systems through the maintenance of good soil conditions.”

Improving soil health is the route to resilience

Sugar beet is one of those crops that lets you know if all’s not well. In its early growth stages, sugar beet plants are far from tough, but they will thrive under the right soil conditions. BBRO were keen to be involved in the Soil Biology and Soil Health Partnership because the sugar beet crop’s performance is impacted so greatly by poor soil health, explains Dr Simon Bowen, BBRO crop progression and recovery lead.

“I don’t believe UK soils are in a terribly degraded state but they’ve lost some resilience, which impacts the crop’s ability to withstand stresses from extreme weather events and sugar beet yields reflect this,” he says.

He cites the 2016 season as a prime example of how soil health can impact on crop performance. “We had monsoon-like rain during June at a time when the sugar beet crop didn’t have large root systems or canopies. Crops just sat in the wet ground for 1-2 weeks and some soils slumped, reflecting an underlying soil health problem.

“It was noticeable that in the same area and on the same soil type, some crops recovered quickly whereas others took a prolonged period to get over the setback. The crops that suffered the most delay also had the greatest yield losses.”

Where soils had slumped, it was difficult to look at the soil and pinpoint why, with no standard way of quantifying the components of soil health, he explains.

In most seasons, 10-15% of potential sugar beet yield is lost due to drought stress and this is another area where soil health plays a critical role in helping the crop through adverse conditions. “Soil health holds the key to unlocking the yield potential of the sugar beet crop. We need a reliable way of measuring it, and this will also help us identify the management practices that improve soils,” he says.

Simon believes many growers are well ahead of science when it comes to how to best manage their soils and are well-placed to help scientists with the quest to develop a standard measure for soil health.

BBRO recognises this and has a farm demo network where growers are using cover crops, applying additions of various organic amendments under different tillage regimes. The aim is to provide a platform for linking measurement to performance and for growers to share what they’ve found out.

“The number of management options are huge, so facilitating discussion and sharing of information between growers is very important,” believes Simon.

To get beyond observational results the industry badly needs a standard set of measures at a reasonable cost, he adds.

“We also need to recognise that the benefits of improving soil health may not have a direct impact on yield every season. Last season the UK sugar beet yield was 10% above average because it rained at the right time, so drought stress wasn’t a factor.

“By improving soil health, we’ll be increasing the soils resilience and improving the ability of the crop to cope under difficult conditions. Expecting to see an immediate result after a management change, such as including a cover crop in the rotation, is unrealistic,” he says.

Research roundup

The Soil Biology and Soil Health Partnership is part of the AHDB’s GREATsoils initiative and runs from 2017 to 2021, £858,869 and BBRO £140,934). It’s a cross-industry partnership with 13 other partners, with NIAB as the lead. The programme comprises a series of interlinked projects, conducted within three main work packages; benchmarking and baselining activities, measuring and optimising long-term impacts of soil management and knowledge exchange.

More information and final reports can be found at www.ahdb.org.uk/greatsoils