Applying all the key nutrients in the spring may bring yield and cost benefits, according to trials results. CPM reports.

By Rob Jones

Recent CF trials have shown that the traditional approach of applying potash and phosphate in the autumn and then nitrogen and sulphur in the spring could be limiting nutrient uptake and yield production.

According to CF Fertiliser’s Ross Leadbeater, applying all the key nutrients as an NPKS compound in the spring ensures they’re available when the plant is growing and can utilise them the best.

“There are positive advantages from applying all these nutrients in the spring, principally because by doing so crops receive the nutrition they require, in the form they need it, when they need it.”

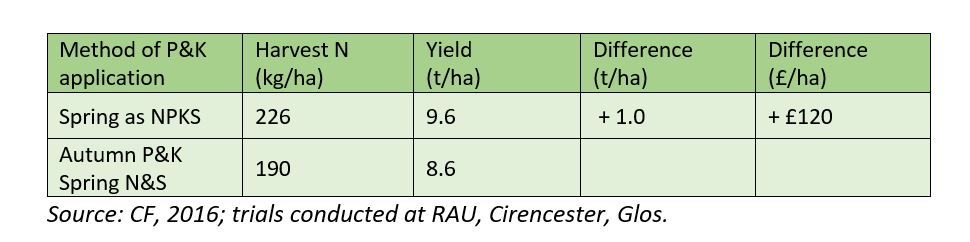

Trials at the Royal Agricultural College in 2016 showed spring-applied CF Heartland Sulphur NPKS (24:8:8 + 8SO3) produced a 1.0t/ha advantage over the split applications approach, he says.

“The Heartland Sulphur was applied during the spring on some plots while others received straight P and K in the autumn followed by just N and S in the spring.

“All the land had indices of P1 and K2 with total applications equalling 200kg N/Ha, 81 kg/ha K20, 127kg/ha P205 and 68kg/ha SO3 across all plots.”

The plots that received the P and K as an autumn application with N and S applied in the spring produced 8.6t/ha whilst those that had all nutrients applied as Heartland Sulphur NPKS in the spring produced 9.6t/ha (see table below).

Fertiliser timing trials, 2016

The financial benefit works out at around £106/t, after factoring in the extra cost of fertiliser, he adds. “With a typical fertiliser application estimated at around £6-9/ha, the savings in labour, fuel and machinery resulting from the single application approach are also substantial.”

Timing tweaks

Timings might differ between milling and feed crops with the premium crops often requiring a late boost of nitrogen between growth stages 35-37 to encourage protein building, Allison Grundy says.

“Many milling wheat varieties won’t start diverting nitrogen into protein production until the crops yield potential has been reached.

“If you don’t reach that point, you might be getting good yields but building protein just isn’t there to hit the required specification.”

CF trials have also shown that four, maybe five, applications are more appropriate if a larger amount of nitrogen is calculated to be applied as opposed to the more traditional three-way split.

“Applying more frequently means the crop will receive smaller amounts each time improving the recovery of nitrogen by the crop.”

Application timing can also be used to manage the canopy. In slow growing years, early nitrogen can be used to build and support tiller numbers and in forward crops delaying applications can help optimise tiller number, she says.

“An optimum to aim for is around 1000-1200 tillers/m² with a view to build around 400-600 ears/m². For more forward crops with 2000 tillers/m², delaying the first application will be beneficial to starve some of this growth off.”

Allison Grundy advises taking a similar approach to nutrition as for other agronomic decisions. “Make the right initial decisions and plan for the best outcome but be prepared to change your approach if weather or other issues dictate this.

“The objective should be to use nutrition to achieve the ‘optimum’ output rather than simply the ‘maximum’ yield. This means focusing on cost of production rather than just yield as chasing those extra few hundred kilos may require an uneconomically high input of N.”

If cold conditions, high disease pressure or other factors look like they will put a limit on total yield, be prepared to adjust application rates and timings to achieve the best outcomes, she advises.